Cheap drones may be changing warfare, but the value of air superiority endures.

The proliferation of small unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has shaken up the military world, fueling concern that UAVs could revolutionize airpower concepts and even negate the need for air superiority as a fundamental objective of airpower strategy. Dr. Kelly A. Grieco and Col. Maximillian K. Bremer’s “air littoral” concept—defining the airspace from the coordinating altitude to the Earth’s surface—argues that increasing numbers of UAVs and one-way attack “drones” have shifted the importance of air control to low altitudes, altering the doctrine of air superiority. Retired Army Lt. Gen. David Barno and Nora Bensahel assert that “drones” have displaced manned aircraft and are now threatening the U.S. Air Force’s relevance with “an almost-existential crisis.”

These perspectives all share another commonality: They suffer from a collective airpower amnesia acquired over a 30-year period in which American airpower reigned supreme against a series of nonpeer rivals. Absent the challenge of air-to-air combat and without the context to understand what could happen in a peer fight, these observers are overstating the impact of UAVs and misinterpreting their tactical role.

The biggest lesson from the Russia-Ukraine war is not how small UAVs are reshaping air warfare, but rather how they are reshaping ground combat.

The term “drone” lies at the heart of the problem. It is, at best, a lazy catchall, covering everything from an out-of-the-box commercial quadcopter to the YFQ-42 and YFQ-44 Collaborative Combat Aircraft autonomous fighters now under development for the U.S. Air Force. Lumping all these aircraft into a single, oversimplified category obscures their unique capabilities and fuels misguided hype.

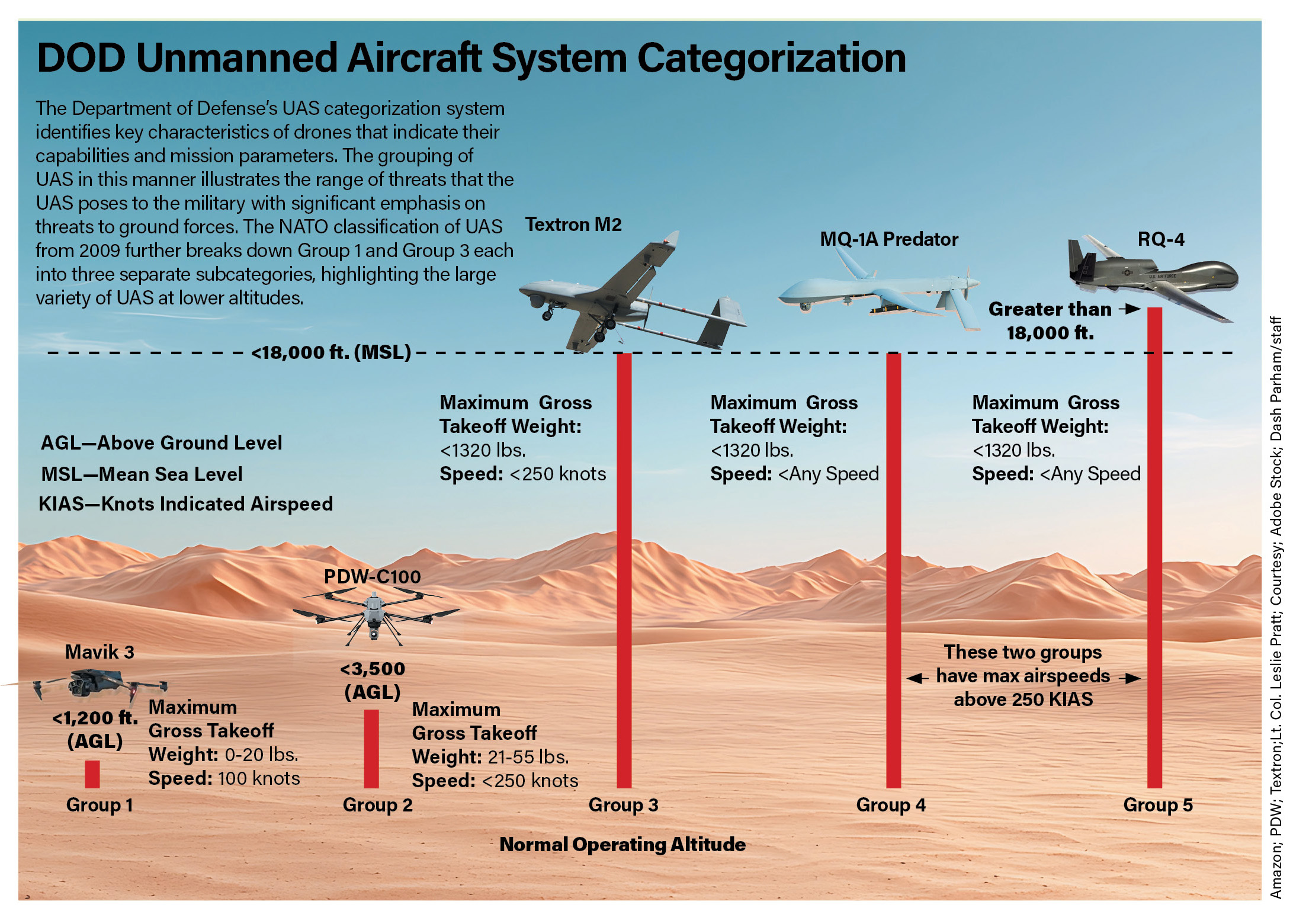

Breaking down UAVs into distinct groups based on weight, operating altitude, and speed as their defining characteristics can help clarify the diversity of this category of aircraft. Groups 1-3 represent small UAVs, which are the aerial weapons employed abundantly in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, causing some to shift airpower assumptions prematurely. These small UAVs frustrate ground operations and excel in reconnaissance, precision strike, and electronic warfare roles. But they do not challenge air superiority, which is defined as the degree of control of the air domain necessary to “enable successful execution of joint operations such as strategic attack, interdiction, and close air support (CAS),” according to Air Force doctrine. Small UAVs lack the capability and capacity to achieve such control because they do not possess the advanced air-to-air combat capability necessary to deny adversaries access to airspace. The fact is, the biggest lesson emerging from the Russia-Ukraine war is not how small UAVs are reshaping air warfare, but rather how they are reshaping ground combat. Neither side has been able to achieve air superiority over the other, resulting in an environment where small UAVs can wreak havoc on both infantry and armor.

The argument that UAVs have created a new domain between the ground and air known as the air littoral proposes an unnecessary redefinition of airspace management below the coordinating altitude (CA)—a combat-tested height that separates fixed-wing and rotary-wing operations. Small UAVs fit within existing doctrine, and air superiority’s fundamental principles remain unchanged. Coordination must begin between the air and ground components, adapting the CA to assign responsibility for targeting. This reinforces established airspace-management doctrine, preserving resources for securing air superiority against peer adversaries like China and Russia, whose advanced air defenses demand robust air control. As with past innovations, adapting to UAVs strengthens, rather than rewrites, the primacy of air superiority as a necessary goal in joint warfare.

Assigning the Army to defend against enemy UAVs below the coordinating altitude and the Air Force to defend above it aligns with current tactics, technologies, and operational concepts. Though UAVs may be relatively new, their underlying operational characteristics are not. As retired Lt. Gen. David Deptula recently commented on the Aerospace Advantage Podcast from the Mitchell Institute of Aerospace Studies, “Drones are simply cruise missiles being used as a substitute for penetrating aircraft delivering PGMs.” Introducing new terms to replace existing ones with the same meaning undercuts a working system and risks confusion over solutions.

Small UAVs provide new capabilities that primarily affect ground operations. Deptula said small UAV’s “most effective use to date is in countering conventional infantry and armor engagements.” Additionally, counter-tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), as well as emerging kinetic and directed-energy technologies, such as SHORAD (short-range air defense) and IRON BEAM, are rapidly diminishing their marginal impact on air operations. Claims of the revolutionary relevance of small UAVs in air operations are rash and simply unsupported by the reality of combat, as recently proven by Israel’s resounding, successful air campaign against Iran, which, lacking air superiority, has had to resort to ballistic missiles and cruise missiles. The U.S. is not doctrinally “woefully unprepared” to counter small UAVs operating below a coordinating altitude based on the past 30 years of successful air operations utilizing proven airspace management practices. Redefining this airspace as an air littoral is unnecessary and redundant. Instead, adapting and standardizing a UAV coordinating altitude for targeting responsibility will enhance efficiency in future operations.

Drones: Evolutionary, Not Revolutionary

Revolutionary technologies fundamentally reshape warfare by opening new domains and contesting control; evolutionary developments, however, merely enhance existing capabilities without altering core principles.

When the Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley sank the USS Housatonic in 1864, it represented a revolutionary development that turned the undersea world into a new domain of warfare. Forever after, naval forces would have to operate in a new world where combat could take place both on the sea and beneath it. By World War II, submarines had become a significant difference-maker in warfare, disrupting shipping and diverting assets to develop anti-submarine technologies, such as sonar, ASW (antisubmarine warfare) aircraft, and depth charges, to counter their stealth advantages. This ultimately redefined naval strategy. Today, the balance of naval power increasingly hinges on the capabilities of submarines.

The advent of the airplane was likewise revolutionary, extending conflict into the vertical dimension and enabling the projection of combat power from the skies. Billy Mitchell envisioned that airplanes would end wars by overflying ground forces to strike cities and strategic industries, attacking the capacity to wage conventional wars. World War II confirmed airpower’s transformative role, though it hardly paved the way to end future wars. Counterair technologies, such as antiaircraft artillery (AAA), surface-to-air missiles, and radar, emerged as vital factors, and, according to airpower strategist Colin Gray, “war had been forever transformed.” Airplanes redefined military strategy, requiring dedicated air forces to secure air superiority.

Today, a growing number of observers are ascribing similar characteristics to small unmanned aerial systems. Yet, unlike submarines or airplanes, which opened new domains of warfare, small UAVs are not so transformational. Deptula pointed out that these low-cost weapons are largely an extension of the ground domain, providing reconnaissance, precision strikes, and electronic warfare capabilities to ground warfighters without compromising air superiority. Furthermore, functioning like cruise missiles or precision-guided munitions, one-way UAVs rely on low-altitude flight, autonomous navigation, and precision targeting to evade radar cost-effectively. What is evident from conflicts like Ukraine’s is that these systems displace existing weapons, rather than offer domain-altering innovations.

This historical perspective clarifies why contemporary claims about “drones” reshaping air superiority are misguided. Assertions that “drones,” as witnessed in the Russia-Ukraine war or Iranian proxy wars, threaten the established doctrine of air superiority, misinterpret their impact and role. Barno and Bensahel’s claim of an Air Force “existential crisis,” where small UAVs supposedly “wrested command of the air from piloted aircraft,” collapses under scrutiny: Their cited Jordan strike was a cruise missile attack, not a drone wresting air superiority, according to Deptula. Their conflation exemplifies the amnesia that plagues the drone hype. UAVs are evolutionary tools that cost-effectively achieve similar effects to cruise missiles and long-range precision fires. Thus, as Deptula claims, “if there is any lesson to extract from the Russia-Ukraine war to date, it is the absolute necessity of air superiority.” This distinction reaffirms the Air Force’s enduring role in securing the skies.

Countering UAVs

Before the mid-2000s, the U.S. Army had embedded SHORAD capability to defend maneuver forces against low-altitude threats. However, according to U.S. Army Air Defense Artillery Capt. Leopoldo Negrete, in the decades that followed, the lack of enemy fixed- or rotary-wing threats in Afghanistan and Iraq led the Army to prioritize point-defense air defense artillery (ADA), such as the Patriot, over SHORAD, thereby removing ADA coverage from maneuvering ground forces. Correctly, the Russia-Ukraine war and the emergence of small UAVs motivated the Army to reintroduce the Maneuver-SHORAD (M-SHORAD) capability, which includes a variant employing a laser called the Directed Energy (DE) M-SHORAD, according to Negrete. The reintroduction of M-SHORAD reestablishes doctrinally proven air defense relationships between the air and ground components to defend the airspace over maneuver forces, regardless of altitude, even while air superiority is achieved.

Other counter-UAV technologies are rapidly emerging. The U.S. Army is working with Raytheon to field a fixed and mobile low, slow, small unmanned aerial vehicle integrated defense system (F/M-LIDS), equipped with a Coyote Block 2 SAM and two different machine guns capable of targeting UAVs. Israel’s Iron Beam anti-air defense laser could soon be operational, reducing the cost-per-shot compared to the kinetic Iron Dome, which costs $40,000 to $50,000 per shot, to $2-$3.50 per laser shot. The U.S. Marines fielded a hand-held Dronebuster system designed to jam the signals UAVs need to operate. As observed in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, UAV loss rates are high due to iterations of electronic attack capabilities, said Deptula. Even if adversaries scale small UAVs into mass swarms, advanced fighters, and networked defenses—like the F-22’s and F-35’s sensor fusion paired with air battle management—they retain the edge in denying air control, keeping superiority beyond “drones’” grasp. No example better illustrates this point than Iran’s launching of more than 170 “drones” and cruise missiles against Israel in early 2024, thwarted by manned U.S., Israeli, and Jordanian fighter aircraft aided by U.S. air battle management. Small UAVs’ psychological toll on ground forces—evident in Ukraine—amplifies their tactical bite, but this intimidation does not translate into air control.

While small UAVs have altered the language of combat in the land domain, the U.S. Air Force does not need to

redefine its doctrine, air superiority, or the pursuit of attaining it. Re-emerging is the codified doctrine for how the air and land components work together to achieve vital air defense for ground forces, allowing the USAF to focus on air superiority and prevent enemy air interdiction efforts in a near-peer fight. The seminal lesson from the Russia-Ukraine war is that freedom of maneuver is severely restricted without air superiority, and a decisive advantage cannot be achieved to meet military and political objectives without it.

Adapting Doctrine: UAVs in Their Place

Adaptation preserves primacy. To account for UAVs in a future conflict, airspace control plans should establish a coordinating altitude suitable for the area of operations to delineate targeting responsibilities between the ground component and the air component. The ground component, nominally through Army M-SHORAD or other ADA capabilities, should own responsibility for Group 1-3 UAVs—low, slow threats—coordinating with the air component commander for by-exception targeting. Group 4-5 UAVs, operating at higher altitudes, suit traditional interceptors (either fighters or surface-to-air missiles), which is why having the joint force air component commander dual-hatted as the area air defense commander is still an appropriate organizational construct. However, as recently demonstrated in operations defending Israel from air assault by Iranian cruise missiles, which are often mischaracterized as “drones,” fighter aircraft may be the only means to intercept these threats down to very low altitudes.

The airspace below the coordinating altitude has long been a contested area. AAA, man-portable air defenses (MANPADs), and mobile surface-to-air missiles create significant tactical problems for fighter aircraft. Additionally, the presence of rotary-wing aircraft at low altitudes requires airspace control measures, such as a coordinating altitude, that deconflicts fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft within an area of operations. Operating at low altitudes carries risks, and the need to deconflict fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft limits traditional fighters’ ability to counter UAVs. This has always presented a problem. Redefining the airspace below the coordinating altitude as the “air littoral” does not solve this problem.

Drones and cruise missiles have not redefined air superiority in Ukraine, the Middle East, or elsewhere. On the contrary, small UAVs have proved necessary precisely because Russia, Ukraine, and Iran have been unable to attain air superiority. In the case of Ukraine, they do not have the aircraft necessary to achieve air superiority and have been denied authority by the U.S. to use long-range weapons to suppress Russian air defenses. Small UAVs alone have demonstrated no capacity to gain air superiority, even at low altitudes. Advanced aircraft such as the F-22 and F-35, and, in the future, the F-47 and collaborative combat aircraft (CCA), paired with air battle management platforms like the E-7 and Control and Reporting Centers, will be needed to conduct offensive counterair missions against advanced surface-to-air threats and enemy aircraft to attain air superiority and provide temporal freedom from effective enemy interference against friendly ground forces. In short, small UAVs thrive where air superiority is absent, not because they redefine it.

To stay ahead, combatant commanders must integrate counter-UAV technology, such as M-SHORAD, lasers, and jammers, into wargaming against peer threats, ensuring the viability of air superiority as it remains the linchpin of future victories. Avoiding the drone hype fallacy ensures resources are bolstered, not bypassed, by this framework. This requires prioritizing budgets for counter-UAV tech, advanced fighters, and air battle management capability to achieve air superiority. Advocating that the U.S. Air Force must pivot to a drone-heavy force based on suppositions derived from the Russia-Ukraine war, a conflict that does not reflect the capabilities or environment that the U.S. is likely facing in the future, is not only reckless but irresponsible.

Air Superiority Unshaken

The Russia-Ukraine war and the Middle East conflicts highlight the tactical value of small UAVs, not a doctrinal crisis. An appropriate coordinating altitude for engagement aligns the roles of air and ground components to combat adversary UAVs effectively without overreacting. Over-focusing on low-altitude, small-payload, short-range drones diverts attention from advanced air forces and missile systems, which continue to pose genuine threats, especially after decades of counterinsurgency eroded high-end combat readiness. The current aim of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) is “to serve as a comprehensive strategic air force capable of long-range airpower projection,” per the DOD’s 2024 annual report to Congress. The USAF must not abandon plans to recapitalize its combat air forces and air battle management capabilities to counter China. This will not happen by diverting money to saturate low-altitude airspace with drone swarms, as suggested by Grieco and Bremer.

The lack of recent air-to-air combat experience against medium-to high-altitude threats, shaped by 20 years of counterinsurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, must not distract our military from prioritizing air superiority, which does not include quadcopters with hand grenades. Against a peer threat, pursuing air superiority in challenging threat environments requires strategic thinking, planning, and budgeting that drives requests; otherwise, the U.S. risks ceding the air domain advantage to its adversaries. Gen. Kenneth S. Wilsbach, Commander of Air Combat Command, summed up this imperative recently: “There’s been some talk in the public that the age of air superiority is over, and I categorically reject that.” Air superiority is “the first building block of any other military operation that you need to establish if you want to achieve objectives,” said Wilsbach.

The emergence of UAVs demands adaptation, not alarm. No time for airpower amnesia: Russia-Ukraine’s stalemate teaches us that the use of drones is evolutionary, not revolutionary. Doctrine endures—air superiority remains a prerequisite for success in major combat. Sustaining this edge requires budgets that prioritize advanced crewed airpower, supplemented with CCA and other UAVs as their capabilities evolve, rather than discarding validated doctrine learned over the past 100 years of airpower employment. That is the drone hype fallacy laid bare—tactics do not trump dominion. The low-cost, mass-deployable nature of small UAVs enhances ground operations and challenges infantry and armor, as seen in the conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, but it does not necessitate a change in the doctrine of air superiority. Commenting on comparisons between a potential invasion of Taiwan and Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, wherein some argue UAVs could thwart the People’s Republic of China’s aims, Adm. Samuel Paparo, Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, said, “Oh let’s just quit on everything. We’ve got some drones. All right, well, the PRC’s got 2,100 fighters, three aircraft carriers, and a battle force of over 200 destroyers.” The U.S. Air Force’s biggest problem is securing air superiority, not an alarmist doctrinal shift, which would almost certainly result in ceding the airpower advantage.

The U.S. Army must collaborate with industry to bolster defenses against UAV attacks, continue standing up M-SHORAD battalions, and refine systems like F/M-LIDS to protect bases and forces. Meanwhile, the U.S. Air Force must sustain investments in advanced crewed and uncrewed aircraft, including the F-47 next-generation air dominance (NGAD) penetrating counterair aircraft (PCA), the F-22, F-35, CCA, and air battle management platforms like the E-7 and Control and Reporting Centers to counter sophisticated adversaries—and maintain the air superiority vital to achieving national objectives. Far from signaling an existential crisis, small UAVs underscore a dual truth: Air superiority remains paramount, and coordinated air and ground component efforts, rooted in proven doctrine, are required to secure victory in future wars.

Lt. Col. Grant “SWAT” Georgulis, USAF, is a Master Air Battle Manager and currently assigned as the Deputy Chief of C2 Inspections as part of the Headquarters NORAD and NORTHCOM Inspector General team. He recently finished a yearlong Air Force National Defense Fellowship at The Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. Lt. Col. Georgulis has served on a combatant command component staff, was an Air Force Weapons School instructor, and graduated from the Naval War College’s College of Naval Command and Staff and Air University’s School of Advanced Air and Space Studies. He previously commanded an E-3G Squadron, the 965 Airborne Air Control Squadron, at Tinker Air Force Base, Okla.