The first wave of Japanese bombers approached Clark Field undetected on Dec. 8, 1941. By the time US airmen realized they were under attack, the bombs were already falling.

Almost all of the American airplanes at Clark—45 miles north of Manila and the main operational base of the Far East Air Force in the Philippines—were lined up neatly on the ground when the strike came at 12:40 p.m. Japanese A6M Zero fighters followed the bombers, dropping down to strafe the ramp. The fighter base at Iba on the western coast of Luzon, 42 miles from Clark, was struck almost simultaneously.

By end of the first day, the strength of Far East Air Force was reduced by half, and it was eliminated as an effective fighting force. The FEAF response was scattered and ineffective. Of approximately 200 aircraft in the Japanese strike force, all but eight returned to their bases on Formosa.

Air superiority established, the land invasion began. The fighting continued for several months, but the Japanese victory was inevitable, leading to a surrender of US forces on May 6, 1942.

It was not as if US commanders in the Philippines had no warning. Ten hours had elapsed since the devastating Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, where in addition to the naval losses, the US air forces were caught on the ground. Now, it had happened again.

When Pearl Harbor was struck at 7:55 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1941, in Hawaii, it was 2:25 a.m. on Dec. 8. Reports reached the Philippines soon afterward. In addition to warning messages received, the movement of Japanese aircraft was detected by radar and ground observers and there were several preliminary attacks.

Maj. Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, chief of the Army Air Forces, called FEAF commander Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton to ask, “How in hell could an experienced airman like you get caught with your planes on the ground? That’s what we sent you out there for, to avoid just what happened. What in the hell is going on there”

The question has never been answered satisfactorily. Pearl Harbor generated 10 official investigations. The senior officers in Hawaii, Adm. Husband E. Kimmel and Gen. Walter C. Short, were relieved of command and forced into retirement. By contrast, there was no official investigation of events in the Philippines, and no one was held accountable.

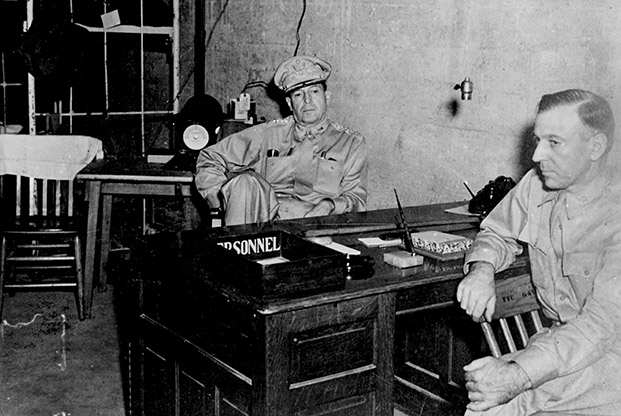

Most historians and analysts place primary blame on Lt. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander of US Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). MacArthur and his loyalists—especially his Chief of Staff, Brig. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland—blamed Brereton. However, a close look focuses on the inexplicable actions of MacArthur and Sutherland.

Planners and strategists in Washington must also bear some fault. The war plan then in effect was unrealistic in its expectations, and MacArthur and Brereton did not have nearly enough resources to carry out its provisions.

There was no real chance of repelling the Japanese attack completely, but it might have been possible to slow the advance and disrupt the Japanese timetable in the Pacific. Any potential strategic value in doing so was lost in the addled US response.

OUTPOST IN THE PACIFIC

The United States had never known quite what to do with the Philippines, which came under its control as a result of the Spanish-American War in 1898, was granted commonwealth status in 1935, and promised independence by 1946.

There was considerable opinion that the Philippine Islands—more than 7,000 miles from the California coast and closer to Tokyo than to Hawaii—were indefensible. The Navy wanted to keep a strong naval presence but the Army, responsible for protection of the bases, regarded the Philippines as a liability.

War Plan Orange in 1928 and the follow-on Rainbow 5 plan in early 1941 visualized nothing more than defensive operations by the Army garrison and the Asiatic Fleet until reinforcements got there.

However, the Philippines had one great military asset: MacArthur, the former US Army Chief of Staff and a field marshal in the Philippine Army since his retirement in 1937. His relationship with the Philippines was special, dating back to 1900 when his father was military governor.

With the prospect of war deepening, MacArthur was recalled to Active Duty in July 1941 as commander of the newly created USAFFE. The Rainbow 5 plan was revised, setting aside the defensive strategy, shifting the emphasis to the offensive, and prescribing “air raids against Japanese forces and installations” in the event of war.

MacArthur’s copy of the plan was delivered by FEAF commander Brereton, who arrived from Washington on Nov. 3. Like other US leaders in the Pacific, MacArthur had received warnings of the possibility of a Japanese attack, but he told Brereton that his own estimate was that hostile action was unlikely before the spring of 1942.

The Army ground forces consisted largely of indigenous Philippine scouts under US command. MacArthur’s critical military strength was provided by his air forces.

CATASTROPHIC LOSSES

DEFENDERS

As recently as 1940, airpower in the Philippines had amounted to a handful of obsolete B-10 and B-18 bombers and open-cockpit P-26 “Peashooter” pursuit airplanes. The first P-40 fighters and B-17 bombers came in 1941. The Philippine Department Air Force was reorganized as FEAF, with subordinate Bomber and Interceptor commands.

The War Department projected almost 600 combat aircraft to be stationed in the Philippines, but that was a distant goal. When the Japanese struck on Dec. 8, FEAF had a total of 181 aircraft—among them 19 B-17s and 91 P-40s—on Luzon, the northernmost of the Philippine Islands.

These aircraft were of great concern to the Japanese. The B-17s could reach the southern tip of Japan, and the Imperial Army and navy air bases on Formosa (the island now called Taiwan) were well within range.

The P-40 interceptors were the only force that could interfere with Japanese air superiority in the Philippines. The P-40 could not match the A6M Zero in agility or climbing speed, but it was the front-line fighter of the Army Air Forces and fully capable in the air defense role over Luzon.

The objective of the strikes at Pearl Harbor and the Philippines was to shield Japan’s drive southward to seize the oil and natural resources of Southeast Asia and the Dutch East Indies. The strategy was to clear the US forces in the Philippines out of the way. Key targets were the fighter bases. If the Japanese could knock out the P-40s, they could operate at will against the rest of the defenders.

Only two landing fields in the Philippines could handle heavy bombers in the wet season. One was Clark, and the other was Del Monte on the island of Mindanao, some 600 miles to the south. As a security measure, Brereton dispersed 16 of his B-17s to Mindanao on Dec. 5 and kept the other three at Clark. The remaining capacity for B-17s, at Del Monte, was reserved for a bomb group due to deploy from the United States.

USAFFE possessed seven radar sets, of which two—one at Iba Field and the other outside Manila—were operational on Dec. 8. Ground observers at critical locations served as additional lookouts, but it took almost an hour for their reports to reach Interceptor Command.

Most of Japan’s carriers were allocated to the Pearl Harbor attack so land-based navy and army aircraft from Formosa would carry out the strike on the Philippines. The plan was to launch them as soon as confirmation of the strike on Pearl Harbor was received. The airplanes were gassed and ready, but a thick fog rolled in at midnight and delayed takeoff.

According to information obtained after the war, the delay caused anxiety among the Japanese, who anticipated that B-17 strikes had been ordered and knew that their defenses were “far from complete” and “would have been ineffective against a determined enemy attack.”

STRANGE INTERLUDE

The first report from Pearl Harbor reached Manila at 2:30 a.m.—five minutes after the attack—in a message from Hawaii to the US Asiatic Fleet, but the information was not relayed immediately to the Army.

USAFFE heard the news from a commercial radio station around 3 a.m. and alerted base commanders. Sutherland awakened MacArthur at 3:30 when official notice was received. At 3:40, Brig. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, chief of the Army War Plans Division, called MacArthur from Washington, D.C., with a longer account.

At 4 a.m. Gen. George C. Marshall sent MacArthur a cablegram directing him to “carry out tasks assigned in Rainbow 5 as they pertain to Japan.” The War Plans Division called again at 7:55 to check on the situation in the Philippines and to give an additional warning.

Brereton, seeking permission to strike the Japanese bases on Formosa, tried to see MacArthur at 5 a.m. but was denied access by Sutherland. With the B-17s standing by for takeoff, Brereton made another attempt to see MacArthur at 7:15 but was again turned away by Sutherland. At 8:50, Sutherland instructed Brereton to “hold off bombing of Formosa for the present.”

In his memoirs, published in 1964, MacArthur said that as late as 9:30, “I was still under the impression that the Japanese had suffered a setback at Pearl Harbor” and that it was even later when “I learned, to my astonishment, that the Japanese had succeeded in their Hawaiian attack.” This claim was not credible, and the memoirs treat the events of Dec. 8 in less than three pages.

At 10 a.m., Brereton checked back with Sutherland, who told him to take no direct action. Finally, at 10:14, MacArthur called Brereton directly and gave him the authority to make the decision on offensive air action.

CONFUSION

Hours earlier, as dawn approached, fighters on Luzon maintained their alert but the first blow fell far to the south. Aircraft from a lone Japanese carrier struck two US Navy locations in Mindanao at 6 a.m., destroying two PBY seaplanes but accomplishing little else.

The fog over Formosa lifted around 7 a.m., and two formations of imperial bombers headed for northern Luzon. At about 9:30, they attacked a landing strip at Tugueraro—no airplanes there that morning—and Baguio, the summer capital of the Philippines.

Meanwhile, as a precautionary measure, FEAF had ordered the B-17 and B-18s into the air and was holding them in a pattern in the vicinity of the base. FEAF pursuit squadrons attempted to intercept the Japanese bombers but were unable to do so. Observers reported that the Japanese were returning home and at 10 a.m. an all-clear signal was sent to US aircraft.

With MacArthur having cleared Brereton to bomb Formosa, the B-17s prepared to land for refueling, loading of ordnance, and crew briefing.

“It required some time to bring in all the bombers from patrol, but shortly after 11:30 all American aircraft in the Philippines, with the exception of one or two planes, were on the ground,” the official Air Force historical account said. However, at 10:15, the main Japanese strike force—108 navy bombers and 84 Zeros—set out for Clark and Iba. At 11:20, radar picked up their approach. The warning to FEAF units, issued through Interceptor Command channels, was not passed on to the bomb group at Clark.

Confusion prevailed. The pursuit group commander directed his available fighters to cover Manila, believing that was the target for the incoming Japanese formations. The P-40s at Clark were held on the ground where pilots “awaited takeoff orders while eating sandwiches sent out to them,” according to historian William Bartsch.

“All during the Clark Field attack there were 36 P-40s and 18 P-35s airborne and covering Nichols Field, Cavite, and Manila, 55 miles south of Clark Field,” Brereton said. “Efforts to get this fighter force to proceed to Clark were unavailing because the one radio set available for fighter-ground communications had been hit in the initial attack.”

CAUGHT ON THE GROUND

The Japanese formation approached Clark in two waves. It “was almost overhead at the time the air raid siren was sounded and the bombs began exploding a few seconds thereafter,” the official Air Force history said.

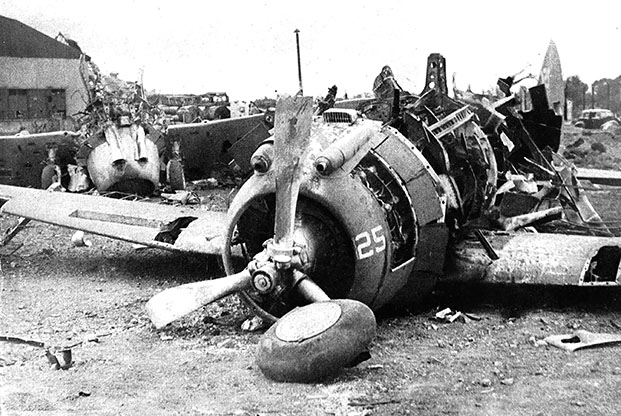

The bombers, flying at high altitude, left the B-17s largely undamaged, but they were followed by the fighters in a low-level strafing attack that was devastatingly effective. “Only one B-17 at Clark was not hit,” according to Brereton.

A few gun crews got their antiaircraft weapons into operation. Most of the shells turned out to be duds and those that were not could not reach the Japanese bombers at altitude. But several P-40s were able to take off and shot down three Zeros.

“We looked down and saw some 60 enemy bombers and fighters neatly parked along the airfield runways,” a Japanese pilot said in postwar interrogation. “The Americans had made no attempt to disperse the planes and increase their safety.”

The other Japanese formation hit Iba at about the same time. “Damage at Iba was, if anything, more severe [than at Clark],” the Air Force history said. “Of the 3rd Squadron’s P-40s, apparently only two escaped destruction. Bombs crashed into barracks and service buildings. Much of the airplane maintenance equipment was lost, and with it, the entire radar installation.”

Of the 181 FEAF airplanes based on Luzon when the Japanese attacked, about 100 were destroyed, and others were significantly damaged in the bombing and strafing attacks. P-40s from Clark and the other US fighter bases shot down seven Zeros and one Mitsubishi G3M bomber.

The B-17s were “thought capable of striking the enemy’s bases and cutting his lines of communication,” said Army historian Louis Morton. “Hopes for the active defense of the islands rested on these aircraft. At the end of the first day of war, such hopes were dead.”

The Japanese soon had command of the air over Luzon. “Except for reconnaissance missions carried out by pursuit pilots, the air force could offer little support to the hard-pressed infantry,” the official history said.

FALL OF THE PHILIPPINES

The primary target for the Japanese naval bombers on Dec. 9 was the Nichols Field fighter base near Manila. Del Carmen and Nielson Fields were struck on Dec. 10, and Nichols was hit again. Tactics were similar to those employed at Clark. The bombers came first, followed by fighters in low-level strafing attacks.

With the radar at Iba destroyed, the only warning was from observers and air patrols, and that was limited. By Dec. 10, Interceptor Command had only 30 pursuit aircraft left, including eight outmoded P-35s, but not counting one or two useless P-26 Peashooters.

Most of the Asiatic Fleet withdrew from Philippine waters, leaving only submarines to contest Japanese naval superiority. The Japanese infantry began its invasion of Luzon on Dec. 10.

The remaining B-17s on Luzon fell back to Mindanao Dec. 11. As the Japanese attacks reached Del Monte Dec. 19, the B-17s were withdrawn to Darwin, Australia. Several B-17 strikes against the invaders were mounted, staging when feasible from Del Monte and Clark, but the results were negligible.

MacArthur conceded Manila and moved his headquarters to the fortress island of Corregidor Dec. 24. Brereton and the remnants of FEAF were transferred to Australia. On orders of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, MacArthur also left the Philippines March 12 to set up a new command in Australia.

The War Department announced March 25 that MacArthur had been awarded the Medal of Honor. This was done at Marshall’s urging and approved by Roosevelt mainly as an effort to counter accusations that MacArthur had abandoned his post in the Philippines.

Lt. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright, commanding all forces in the Philippines, surrendered unconditionally on May 6. MacArthur expressed his strong disapproval.

JUDGMENT

In early 1942, Brereton moved on to a new assignment. When Maj. Gen. George C. Kenney arrived to take command of air forces in the southwest Pacific, Sutherland told him the loss of aircraft on the ground in the Philippines had been Brereton’s fault. In 1945, Sutherland said that Brereton had not obeyed a direct order before the attack to move all of the B-17s to Del Monte.

In his memoirs, published in 1946, Brereton laid out his side of the story. Among other things, he said that, “Neither General MacArthur nor General Sutherland ever told me why the authority was withheld to attack Formosa.”

MacArthur reacted with a 400-word statement to The New York Times. “General Brereton never recommended an attack on Formosa to me, and I know nothing of such a recommendation having been made,” he said. “Such a proposal, if intended seriously, should have been made to me in person by him.” In any case, an attack on Formosa “would have had no chance of success.”

Furthermore, “the overall strategic mission of the Philippine command was to defend the Philippines, not to initiate an outside attack,” MacArthur said.

As for the B-17s, “I had given orders several days before to withdraw the heavy bombers from Clark Field to Mindanao, several hundred miles to the south, to get them out of range of enemy land-based air.”

None of this is substantiated in records or documents from 1941, however. Brereton attempted several times to present his proposal “in person.” There is no explanation of why MacArthur did not find time to consult with the commander of his most important forces.

The mission under War Plan Rainbow 5 was not defensive. It was to take offensive action. MacArthur had been specifically reminded to implement Rainbow 5. It can be debated whether it would have worked, but a B-17 strike was of definite concern to the Japanese.

The plan to relocate some of the B-17s to Del Monte was proposed by FEAF staff in November. Sutherland agreed, with reluctance, on the condition that the move southward would be temporary. Brereton ordered the deployment. There is no indication that MacArthur took any interest in it prior to the attack.

Hap Arnold summed it up reasonably well in his memoir Global Mission in 1949. “I have never been able to get the real story of what happened in the Philippines,” he said.

___

John T. Correll was editor in chief of Air Force Magazine for 18 years and is a frequent contributor. His most recent article, “Against the MiGs in Vietnam” appeared in the October issue.