Russia’s use of inexpensive Iranian drones in Ukraine imposes a costly bill for defending against low-cost weapons.

One of Russia’s most formidable weapons in its punishing invasion of Ukraine is a noisy, slow-flying, propeller-driven kamikaze drone manufactured in Iran.

The Shahed-136, and its smaller sibling, the Shahed-131, is a far cry from Russia’s advanced Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, Iskander ballistic missile, or other high-tech weapons that Russian President Vladimir Putin showcased before his February 2022 offensive. That show of capability was intended to dissuade the United States and its partners from coming to Kyiv’s aid.

Ukrainian forces say they have shot down most of the Iranian drones, but enough have gotten through to pummel much of Ukraine’s electrical grid. The unmanned aerial systems (UAS), deployed to operate like loitering munitions, have tied up much of Ukraine’s patchwork air defenses and added to Russia’s firepower as its supply of long-range strike systems has dwindled.

Historically, there’s a lot of mistrust between Russia and Iranians, but they need each other right now.CIA Director, William Burns

“Rare and expensive became cheap,” Bernard Hudson, the former director of counterterrorism at CIA, said at Harvard’s Belfer Center in October. “Air power is no longer tied to airfields.”

The most worrisome developments may be yet to come. The White House has warned that Russia’s acquisition of the drones could be the first step in a “full-fledged defense partnership” that may lead to the establishment of a joint production line on Russian territory and two-way security cooperation.

A Russian move to provide technical support to Iran’s forces would be an ominous and unanticipated twist in a war that has already led to the destruction of more than 1,000 Russian tanks, killed thousands of civilians, and strained Western arsenals.

It could add to Iran’s ability to threaten U.S. forces and their allies and partners in the Middle East. It could also help Tehran better endure the international sanctions Washington and its allies have imposed because of Iran’s nuclear program.

“Historically, there’s a lot of mistrust between Russians and Iranians, but they need each other right now,” said CIA Director William Burns on PBS’ NewsHour Dec. 16. “I think it’s already having an impact on the battlefield in Ukraine, again, costing the lives of a lot of innocent Ukrainians. And I think it can have an even more dangerous impact on the Middle East as well, if it continues. So, it’s something that we take very, very seriously.”

Iran’s drone program began in the 1980s during its nearly eight-year war with Iraq. Iran was the largest international consumer of U.S. military equipment in the 1970s, with a modern air force equipped with U.S.-made F-4 Phantoms, F-5 Tigers, and F-14 Tomcat fighters.

But the overthrow of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the pro-Western Shah of Iran, in 1979 shattered U.S.-Iranian ties. The revolution, the storming of the U.S. embassy, and the hostage crisis that resulted froze out Iran from Western arms markets.

As the years went by, Iran developed its own ballistic missile capabilities along with drones.

“UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) are Iran’s most rapidly advancing air capability,” a report from the Defense Intelligence Agency warned in 2019.

That year, Iranian drones attacked the oil processing facility at Abqaiq, Saudi Arabia. The U.S. charged that Iranian drones were behind an attack on a tanker ship, the Mercer Street, off the coast of Oman in 2021. Iran also provided drones to militias in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Lebanon. Iranian-made drones were used to attack U.S. and allied forces at Al-Tanf Garrison in southeastern Syria and Erbil, Iraq, in multiple strikes since 2021.

“Iran does not have the capabilities to build its own air force that could compete with ours,” said Ryan Brobst, a research analyst at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. “Nor was it able to purchase sufficient aircraft from China or Russia, and this forced Iran to turn to other asymmetric ways to compensate. The way they did so is … by using drones and ballistic missiles to achieve the same results, which is hitting targets from long ways away without the use of conventional aircraft. And they also had to do this efficiently and cheaply, because they have a much smaller economy.”

The Gambit Worked

Drones “present a new and complex threat to our forces and those of our partners and allies,” USMC Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr., who was serving as commander of the U.S. Central Command at the time, told the Senate Armed Services Committee in 2021. “For the first time since the Korean War, we are operating without complete air superiority.”

As the drone threat grew, the U.S. and allied forces in the region have fired air-to-air missiles from fighters to blast the drones out of the sky, a costly but necessary solution to protect lives. The low-cost drones impose serious costs on the U.S. and its allies this way, as the cost of an air-to-air missile far exceeds that of the drones. Training to counter these small UAVs has become one of the military’s top priorities and a way to supplement ground-based defense like Counter-Rocket, Artillery, Mortar (C-RAM) rapid-fire guns.

“AFCENT’s strategy for dealing with the threat of Iranian unmanned aerial systems begins with deterrence,” said Lt. Gen. Alexus G. Grynkewich, the commander of Air Forces Central, in an emailed response to questions. “By maintaining robust, ready and lethal forward forces, alongside our partners throughout the region, we deter Iran and its proxies from attacking U.S. and partner forces with UAS. Our diverse intelligence collection detects UAS production, shipping, and storage.”

Air Forces Central regularly conducts counter-UAS exercises, including sometimes missions flown by the commander himself. One of Grynkewich’s top priorities—other than flying missions in support of the allied forces as part of Operation Inherent Resolve, the anti-ISIS campaign—is counter-UAS exercises as part of a broader push for better integrated air and missile defense in the region coordinated with U.S. allies and partners

“We maintain a range of kinetic capabilities designed to deny and delay UAS attacks, including both nonkinetic options and shooting down UAS using armed aircraft, both of which we train for routinely across the joint force and with our partners and members of the coalition,” Grynkewich said. “Finally, we defend personnel and installations with a range of systems which create a layered defense, synchronized with interdisciplinary, multinational teams to maximize efficiency and effectiveness. The UAS threat is constantly evolving, and so too are the ways and means by which we mitigate this threat. Like the threats from theater ballistic missiles and land-attack cruise missiles, no country or force operating in the Middle East region can completely mitigate the UAS threat alone—this is why regional integrated air and missile defense is my top focus area and a key focus area for the combatant command as well.”

But unlike U.S. forces and their allies in the Middle East, Ukraine does not have the kind of comprehensive air defense that AFCENT relies on, nor the firepower to back up a deterrence strategy.

The Shahed-136 and Shahed-131, or Geran-2 and Geran-1 in Russian nomenclature, are able to change targets in mid-flight, but are of only limited utility against hardened military targets. They are effective against soft infrastructure targets, however, such as in the case of attacks on Saudi oil infrastructure and the Mercer Street tanker.

“They don’t have very big warheads,” according to Michael Knights, a Middle East military and security expert at The Washington Institute. “They’re quite accurate, but they’re also quite easy to shoot down. So what you’re ideally hitting is an undefended, valuable target.”

The Biden administration says that Iran has provided Russia with hundreds of drones and has also sent technical experts from its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps to Crimea to provide technical support and to train the Russians in how to use them.

“There are a number of benefits for Iran seeing how they do in a little bit more modern battlefield,” said John Hardie, a security expert at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. “With Iran, its various drones and missiles, it’s proliferated, it’s always a learning opportunity. That’s No. 1. Number 2 is perhaps status. It’s legitimizing for the regime and for the revolution. Number 3, poking the West in the eye and distracting the United States and its Western allies, and perhaps drawing their attention away from the Middle East.”

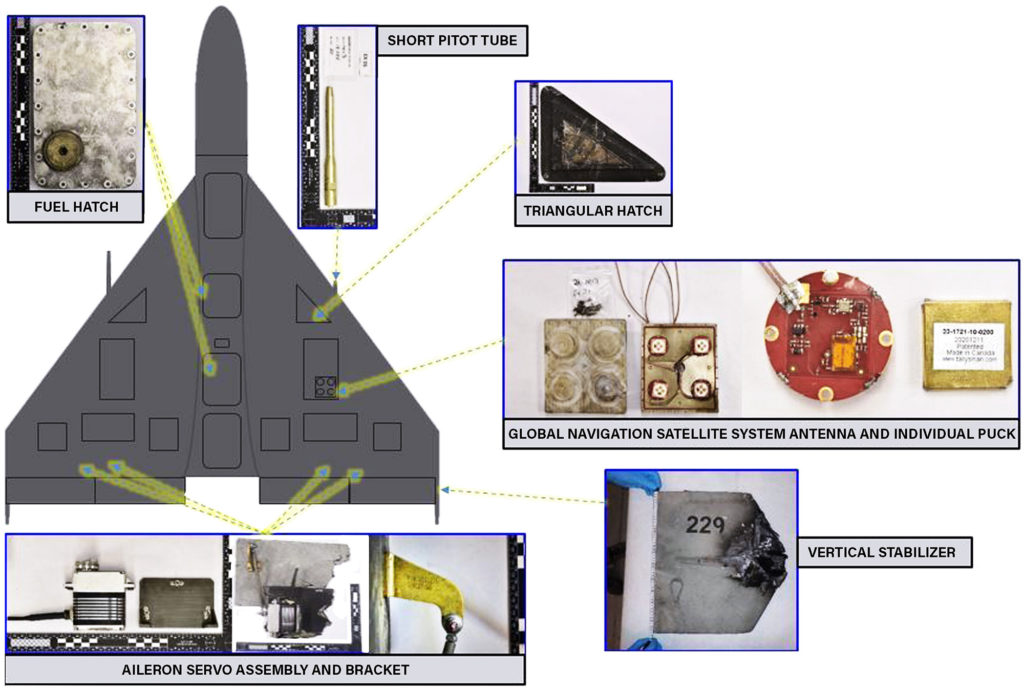

According to a report by the Royal United Services Institute, a British think tank, the Shahed-136 has a range of more than 600 miles and usually cruises at a speed of about 100 miles per hour, slower than a basic Cessna. The drone has inertial guidance and satellite navigation receivers. The drone is best at hitting fixed targets. The Shahed-131 is a smaller but visually identical version of the Shahed-136, according to the U.S. Army’s Training and Doctrine Command.

According to Conflict Armament Research, wreckage of the Iranian-made drones it inspected in Ukraine found that they “include high-end components, such as semiconductors and tactical-grade inertial measurement units, that have been sourced outside Iran.”

On Oct. 10, Russian forces used drones, Kalibr cruise missiles, and Iskander ballistic missiles to carry out a new strategy that has focused on targeting Ukraine’s electrical grid and power stations. The aim has been to deprive millions of Ukrainian civilians from heat and electricity.

By launching the drones along with cruise and ballistic missiles, Russia’s aim has been to overwhelm Ukraine’s air defenses. Russian strikes have been carried out from Crimea, or from Russian airspace or ships in the Black Sea. Russia is also launching many attacks in the middle of the night to catch Ukrainian defenders off guard and make it hard for air defense teams to spot their targets.

Those launching sites are generally beyond the range of Ukrainian weapons, meaning Russian forces have had a sanctuary. The U.S. has refrained from providing Ukraine with long-range ATACMS missiles that could strike deep into Russia, a policy that Biden administration officials say is aimed at reducing the risk that the Ukraine conflict could escalate into a direct U.S. and Russian confrontation. It has also extracted a commitment from Kyiv that the HIMARS launchers it has provided with GMLRS (Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System) rockets won’t be used to strike Russian territory.

As long as Russia can launch drones, it is extracting a steep cost from Ukrainian forces.

Experts such as Knights and Hardie reckon the drones are relatively cheap and cost around $20,000—though putting a precise monetary figure on Iranian and Russian military cooperation is difficult.

“There are lots of things the Russians have got that the Iranians want,” Knights said. “When it comes to technology, when it comes to joint production of materials, when it comes to nuclear research. Iran’s other friends include North Korea. If you’re the Iranians, and you’re highly isolated, Russia gives you a U.N. Security Council veto-holding friend.”

The relatively crude Iranian drones present a difficult cost imposition on Ukraine even if its air defenses are at their best. The estimated cost of each missile fired, for example, by Ukrainian ground-based air defenses such as the indigenous S-300, is up to $1 million. Even less advanced systems, such as U.S.-made Stinger man-portable air defense system (MANPADS) launchers, still cost tens of thousands of dollars per missile.

“As a competitive strategy, where you force your opponent to put a lot of their effort into blocking something that’s very cheap for you to do, it’s very effective,” Knights said. “It imposes costs on your opponent—higher costs than you’re paying.”

Ukraine has a patchwork collection of surface-to-air missiles, manned aircraft with air-to-air missiles, MANPADS, anti-aircraft guns, and other defense methods such as electronic warfare.

“There’s a lot of counter-UAS going on in Ukraine right now,” said Tom Karako, an air and missile defense expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Russia’s drone attacks are essentially a war of attrition. Karako points out that air and missile defense is an area that even the U.S. admits it has little excess capacity even for its own needs.

Karako said advanced, expensive surface-to-air missile systems are not ideal for taking on small, slow, inexpensive drones. Instead, the better solution would be electronic warfare to disable the drones, or less costly anti-aircraft guns, Stingers, and Avenger systems, which use Stinger missiles mounted on a vehicle.

Biden Gives Ukraine Patriots and JDAMs

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and U.S. President Joe Biden at the White House, Dec. 21, 2022. White House photo

“The cost per kill is a challenge,” Karako said of counter-UAS efforts. “This is a universal problem.” The United States agreed to send a Patriot air and missile defense system to Ukraine and provide precision-guided munitions, a major step in arming Ukraine as its war with Russia approaches the one-year mark since Russian forces invaded in February 2022.

Amid a Russian barrage of drone, ballistic missile, and cruise missile attacks on Ukrainian infrastructure targets, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy visited Washington, his first trip abroad in 10 months, wearing his signature tactical green sweater and trousers, and expressing gratitude and a plea for still more help.

The State Department said the U.S. was making its “first transfer of Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAMs), which will provide the Ukrainian Air Force with enhanced precision strike capabilities against Russia’s invading forces.” In January, the U.S. upped the ante with Bradley Fighting Vehicles. But while Congress has authorized the training of Ukrainian pilots on U.S.-made F-16s, the U.S. has yet to offer those weapons out of concern that such long-range capability would be viewed as escalatory by the Russians.

The $1 billion Patriot is an integrated air defense system, consisting of interceptors, radar, command and control, and other support elements. It takes about 90 people to man such a battery. However, it will be several months before Ukraine can field the system.

“Patriot is one of the world’s most advanced air defense systems, and it will give Ukraine a critical long-range capability to defend its airspace,” a senior U.S. defense official told reporters. “It is capable of intercepting cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, and aircraft. It’s important to put the Patriot battery in context for aired defense. There is no silver bullet. Our goal is to help Ukraine strengthen a layered, integrated approach to air defense that will include Ukraine’s own legacy capabilities, as well as NATO standard systems.”

U.S. military aid to Ukraine has surpassed $21.5 billion in total weapons and other security aid provided by the U.S. since the start of the war in February.

Providing JDAMs signals a significant move to strengthening Ukraine’s Air Force. The U.S. did not disclose the exact munitions it would provide, how many aerial munitions, or the monetary value of those weapons. JDAM kits are fitted to unguided bombs.

Much of the aid has come by drawing down existing U.S. arms under Biden’s Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA), while the balance comes from other accounts, such as the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI).

The U.S. aid marks a significant step in its plan to improve Ukraine’s air and missile defense, fulfilling a long-standing request from Kyiv. Patriot is America’s most advanced tactical air and missile defense system, and each interceptor missile costs more than $4 million. Ukraine has been pummeled by Russian missiles, many of them launched from Russian aircraft. The Patriot provides a long-range defense capability Ukraine has not previously had.

The Biden administration has refrained from providing long-range systems to Ukraine in an effort to prevent escalation. While it has provided the High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS), for example, it has so far declined to provide the longer-range Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) for HIMARS.

Ukraine has carried out bold attacks into Russian territory with its own weapons. It blew up a bridge connecting Russia to Crimea, which Russia occupied and annexed in 2014. An air base deep inside Russia was targeted and several of Russia’s strategic bombers were damaged in an attack Ukraine has not denied. American officials maintain Ukraine is free to make its own military decisions with non-U.S. origin weapons.

The U.S. said it was not concerned about any escalatory effect of providing the Patriot battery. “This will be an air defense capability among others that they’re being provided as part of an integrated air defense system,” a senior military official said. “It is by default, by nature, a defensive system.”