In the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, as Washington prepared for war in Afghanistan, the US pursued overflight, landing, and basing rights in Central Asia. This vast, predominantly Muslim zone surrounding Afghanistan was one in which America had little access or influence.

Uzbekistan, however, was an attractive power projection locale. The US moved to secure basing rights at an old Soviet air base near the Uzbek towns of Karshi and Khanabad, 90 miles from Afghanistan, and at Manas airport in Kyrgyzstan. The US and Uzbekistan quickly signed a status of forces agreement granting use of Karshi-Khanabad (K2) Air Base at no cost.

This hasty “marriage” lasted only about four years. The bilateral relationship faltered, and the US response to the Uzbek government’s harsh crackdown on a spring 2005 domestic incident accelerated the decline. By fall 2005, Uzbekistan had evicted the US from K2.

|

|

Few, at the start of Operation Enduring Freedom, would have predicted K2’s swift demise. K2 became a bustling hub of action, with roughly 1,000 of the Army’s 10th Mountain Division among the first to deploy there. Eventually, hundreds of active duty, Guard, and Reserve airmen and soldiers operated there, coordinating surface shipments and supporting the 416th Air Expeditionary Group’s C-130 and C-17 cargo missions.

The status of forces agreement, according to analyst Kurt H. Meppen, showed America’s commitment to Uzbekistan’s future, “thereby strengthening the Karimov regime internally and in the region.”

The accord opened the door for extended cooperation. President George W. Bush and President Islam A. Karimov in 2002 signed a more substantial “Framework Agreement,” deepening their partnership in fighting terrorism and benchmarking reform efforts. In a classic quid pro quo, the US provided substantial funding for military hardware, security services, and US Export-Import Bank credits, and Uzbekistan promised to accelerate democratization, bolster human rights, and improve freedom of the press.

In spite of these agreements, trouble was brewing on Karimov’s home front. Regional expert Fiona Hill with the Brookings Institution said that nonsensical economic policies pushed Uzbeks into “subsistence survival strategies.” The problem was compounded by government repression that bred vast discontent and a political succession struggle that further agitated the people.

Marking the Report Cards Many Uzbeks turned to underground organizations including the Islamic activists of Hizb-ut-Tahrir and the terrorists of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan. Tension was not only evident on Karimov’s home front; his partnership with the US was also faltering.

Washington’s initial goodwill toward the Karimov regime cooled. More strain resulted when Karimov began insisting that the US pay for the use of K2.

|

USAF airmen carry gear back to their unit during a shift change at a guard booth at K2 in 2005. On the flight line are USAF C-130 cargo aircraft. ) USAF photo by TSgt. Scott T. Sturkol) |

Congress began using the Framework Agreement as a report card for Uzbekistan’s progress toward reform, and Karimov was definitely not making the grade. Due to Uzbekistan’s lack of progress toward democratization, the US held back FREEDOM Support Act funding. (This legislation was the main US means of assisting former Soviet republics in transitioning out of communism.)

Also, International Military Education and Training and Foreign Military Financing funds were curtailed because of human rights concerns. Karimov chafed at losing aid he had gotten accustomed to receiving, but the US government’s hands were tied by the legislation.

Karimov had learned the US paid Kyrgyzstan large annual sums for use of Manas. K2 was a military airfield, and the US saw it simply as an aspect of bilateral military-to-military ties. Manas, on the other hand, was a civilian airport, so the US felt it appropriate to pay for access.

After fruitless negotiations, Uzbekistan began to curtail flying operations at K2, but this brought no payoff, and the US foreign policy apparatus was blindsided by what was about to happen.

Bad Days Domestic turbulence worsened. In May 2005, it exploded in Andijan, the capital of Uzbekistan’s easternmost province. In the May 12-13 “Andijan incident,” 23 local Muslim businessmen, imprisoned on charges of religious extremism and connections to terrorism, were undergoing trial. On the night of May 12, armed militants stormed the prison to protest the trials and freed hundreds of inmates, some of whom joined the militants in seizing local administration buildings.

Throughout the morning and afternoon of May 13, thousands gathered in the main square to express their grievances, hoping for an audience with President Karimov. Uzbek security services surrounded the crowd and began shooting and pursuing those who fled—ultimately killing scores, possibly hundreds, of men, women, and children.

|

|

The US demanded to know what had happened. At a press briefing on May 18, State Department spokesman Richard Boucher stated, “It’s becoming apparent that very large numbers of civilians were killed by the indiscriminate use of force by Uzbek forces.” Boucher called for a “transparent accounting to establish the facts,” and also mentioned that militants may have had a role in the attack on the prison and other government facilities.

Since it was not clear if Uzbekistan attempted to target militants but killed civilians by accident, the executive branch was initially tentative about condemning Karimov for his harsh response.

Second, the US wanted to maintain rights to K2, a key logistics node in the air network between Europe and Afghanistan. The Defense Department clearly acknowledged that K2 was “undeniably critical” to OEF.

In addition to these near-term goals, the US intended to sustain bilateral relations over the long run. The State Department was quick to affirm US strategic interests in anti-terrorism cooperation, and the White House immediately expressed concern that “terrorists” from the prison might be a threat to US interests.

US policy-makers also wanted Uzbekistan to reform politically and economically. America had poured massive amounts of reform-oriented aid into Uzbekistan since its independence, and expected a return on its investments. On May 17, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice affirmed Washington’s relationship with Tashkent, but added that the US “held all countries equally responsible to engage in human rights practices that are sound and to engage in … democratization and openness.”

|

|

In an attempt to answer the ever-increasing domestic demands for a full accounting, Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), and Sen. John Sununu (R-N.H.) flew to Uzbekistan on their own initiative to meet with members of opposition groups and Andijan eyewitnesses. At a May 30 press conference, the trio said the events were “shocking, but not unexpected” in such a country. The Senators called for a complete investigation, and announced that a bilateral relationship is “very difficult, if not impossible, if a government continues to repress its people.”

Uzbek officials refused to meet with the Senators.

|

|

Journalists sensed an apparent rift between State and Defense in the weeks following the tragedy. A senior diplomat told the Washington Post, “There’s clearly interagency tension,” admitting that State seemed “extremely cool on Karimov,” while DOD wanted to avoid upsetting Uzbekistan.

The Andijan Refugees The public perceived the security vs. democracy dilemma as the media hinted that DOD worried about losing K2, and thus pragmatically opposed a NATO inquiry into the killings, while State seemed concerned that the US would lose credibility by supporting a brutal government.

After State concurred with international demands for an investigation and declined Karimov’s invitation to send observers to the Uzbek inquiry, Karimov countered by restricting night flights and curtailing C-17 operations at K2. Furthermore, Karimov and two other Central Asian Presidents jointly called for members of the coalition supporting Afghanistan operations to establish a date to end use of their nations’ infrastructure.

|

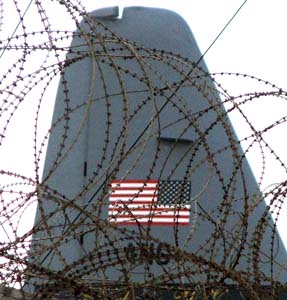

The tail of an Air National Guard C-130 can be seen through a tangle of concertina wire at K2. ( USAF photo by TSgt. Scott T. Sturkol0) |

Perhaps the greatest source of irritation for the Uzbeks was the US decision to airlift Andijan refugees. After the violence, hundreds of residents had fled across the border into Kyrgyzstan, becoming refugees protected by the United Nations. The Uzbeks wanted to question the residents, whom they described as “escaped criminals and … suspected rebels.”

The US negotiated with the UN to airlift one group of refugees to Romania on July 28; a courier delivered a demarche from Uzbekistan to the US Embassy in Tashkent on July 29, invoking the SOFA’s 180-day termination clause. A second group of refugees was airlifted out of Kyrgyzstan on Aug. 2; the official announcement of US eviction from K2 was made the next day.

|

|

The eviction notice effectively gave the United States 180 days to vacate K2. However, the US had already begun adjusting operations. It transferred search and rescue aircraft to Bagram, Afghanistan, and because of Uzbek complaints of runway damage, rerouted C-17 flights through Manas. On Nov. 21, the US officially ceased operations at K2—well ahead of the 180-day deadline.

Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld had visited Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in July 2005, shoring up America’s sustained presence in Central Asia, but he did not visit Uzbekistan. Secretary of State Rice similarly gave Uzbekistan a cold shoulder, choosing not to visit while touring Central Asia in October.

Karimov took the hints, and turned instead to those who affirmed his actions in Andijan. Throughout the fall, he solidified a partnership with Russia by hosting a joint military exercise, signing an alliance treaty, and lauding Russia as “the most reliable bulwark and ally.”

A Two-Pronged Approach Uzbekistan’s counterreactions prove the United States did not achieve its policy aims. The US hoped for a full accounting of the killings, but got none. To the contrary, adding America’s voice to the multilateral choruses of condemnation effectively conceded Uzbekistan to the Russians, thereby undermining both long-term relational and reform goals.

Nor was the US aim of keeping access to K2 realized; the refugee airlift effectively slammed the door on that. Further, the two major “non-visits” did not align with any of the United States’ four goals. Instead, they did more harm than good and contributed to Uzbekistan’s realignment with Russia.

Access to Central Asia is essential to US and NATO operations in Afghanistan. But the late 2005 departure from K2 left the US with Manas as the sole air base in the region.

|

A1C Janine Sivak, a security forces airman, guards an entry to K2 before the US withdrawal. ( USAF photo by TSgt. Scott T. Sturkol) |

The Air Force has witnessed, on an almost continual basis, the precariousness of its position at Manas. Minor incidents and made-up allegations have been repeatedly used by Russian-controlled media to foment anti-American sentiment around Manas. Moscow went so far as to pressure the Kyrgyz government to oust the US from Manas in 2009. Even now, it is still unclear whether the government installed this spring will let the current lease expire, extend previous agreements, or attempt to extract from the US even greater usage fees and developmental aid.

What can the US do to pre-emptively “lead-turn” future Andijans and attempts to expel American forces? Finding tools to engage nations that are helpful in prosecuting overseas contingency operations—yet are deeply steeped in their Soviet past and under intense Russian pressure to show the US the exit door—is indeed a tall order.

Policy-makers and airmen can take a two-pronged approach to set up the lead-turn. The first prong is to turn the tide in the “battle of the narrative” via public diplomacy. Relatively minor incidents are long remembered by locals, while major positive contributions are soon forgotten by elites operating from a “what have you done for me lately?” mind-set. The military leadership needs to continuously remind their hosts about the benefits of the American presence.

The second prong in securing US interests is to assist the local population with “basic blocking and tackling” of democratization, economic growth, human rights, and other aspects of good governance. This will remind all parties that there are broader issues at stake.

These approaches will help both the US and the host nation meet their immediate military and political needs while simultaneously preparing for the day when US troops draw down or leave. The US may have lost K2, but there is still much in Central Asia to win.

Lt. Col. Scott G. Frickenstein is analysis branch chief in the Force Support Division on the Joint Staff/J8. He has written extensively on statistics, military professionalism, and Central Asian security. This is his first article for Air Force Magazine.