Is the Pentagon’s version of man- aged health care in stable condition, or should it be placed in intensive care? The answer depends on whether you are listening to congressional analysts, Pentagon officials, advocacy groups, or military retirees.

The Tricare system–so called because it combines the medical programs of the Air Force, Army, and Navy–has become the focus of a major Washington debate, one that extends well beyond the specifics of the plan itself. Issues surrounding the program include fundamental questions about the proper size of the nation’s postCold War defense medical establishment, as well as the promise of lifetime health-care benefits to military retirees and dependents.

One concern centers on what would happen if DoD decides to slash the size of its dedicated medical force, keeping only enough to carry out wartime functions. That move would seriously jeopardize the stability of the Tricare system. Even now, before the imposition of such a major reduction, military retirees have trouble gaining access to the system. They claim they are being shut out as a result of base closures and the overall drawdown of recent years.

In addition, there is the issue of retirees who, at age sixty-five and over, are eligible for Medicare and who up to now have been able to use the military medical system. Under Tricare, these retirees will be bumped out of the defense medical system altogether. (See “Base Closure and Retiree Health Care,” July 1995, p. 74, and “Health Care in the Lurch,” July 1995, p. 3)

The Road to Tricare

Tricare is the successor to the Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services (CHAMPUS), which actually has been incorporated into the new program as one of three basic health-care options.

Congress created CHAMPUS in 1966 under Public Law 89-614 specifically to handle the needs of active-duty dependents and military retirees and their dependents. Before 1966, those beneficiaries who could not get treatment in a military facility had to arrange and pay for their own medical care through the private sector.

Until the mid-1960s, this was not a big problem. Few beneficiaries experienced problems of access because space-available health care in a military facility was plentiful. The main reason was that, for most of the nation’s history, the number of active-duty members, dependents, and retirees using the system has been small.

In the mid-1960s, however, the situation began to change dramatically. During the Cold War, the nation for the first time maintained a large standing military force, which eventually produced a major numerical increase in retirees, dependents, and survivors. Moreover, the number of married active-duty members increased greatly, creating a corresponding rise in the number of dependents and placing a large new demand on the medical system.

For this growing pool of patients, access to military health care began to grow more difficult. It became apparent that many retirees could not gain access to military health-care facilities even though they were too young to enter the Medicare system, and they did not have the same advantages as federal civilian workers with their health-care plan.

Congress, seeking to redeem what it termed “the fading promise” of health care to retirees and to provide care to active-duty dependents not located near a military medical facility, passed the law that authorized CHAMPUS. It became effective January 1, 1967.

CHAMPUS was the military’s version of a private indemnity (fee for service, or FFS) health-insurance plan, providing coverage to active-duty dependents, retirees and their dependents under age sixty-five, and survivors (also under age sixty-five) of deceased service members, when they could not get care at a military facility. Unlike private health plans, CHAMPUS does not require premiums, but beneficiaries do share the cost of coverage.

Unfortunately, in the late 1970s and 1980s, overall costs for military health care, including CHAMPUS, began to rise at a much greater rate than was the case in the private sector.

A March 1995 General Accounting Office (GAO) report, “Defense Health Care: Issues and Challenges Confronting Military Medicine,” stated that the cost of military health care rose some 225 percent in recent years, compared to 166 percent for the nation as a whole. The medical portion of the defense budget doubled, rising from three percent to six percent; much of the increase stemmed from the growing cost of CHAMPUS service, which rose by 350 percent.

Unexpected Crunch

DoD had not predicted this major new spending requirement, which caused shortfalls in CHAMPUS funding that totaled more than $3 billion during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The GAO report, while noting that there had been a broad, nationwide rise in medical costs, went on to cite two additional specific problems that had helped produce the increased costs of CHAMPUS service.

The first was the expansion and changed nature of the beneficiary pool. The larger pool contained a higher percentage of people actually using CHAMPUS; the number of users went up by 162 percent between 1981 and 1990. Outpatient visits increased by 200 percent. In fact, a separate DoD study found that military beneficiaries use health-care services some fifty percent more frequently than do civilians in standard FFS health-care plans.

The second problem cited by GAO was an alleged propensity of military hospitals to increase their work loads to get additional funding. Traditionally, DoD allocated funds to hospital commanders based on historical trends in the work load, providing incentives for administrators to hospitalize patients for periods longer than necessary.

The recent GAO report also stated that prior to implementation of the Defense Enrollment/Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS) in 1981, the CHAMPUS program was vulnerable to fraud and abuse. Before DEERS, estimates indicate, DoD lost $40 million annually in the form of services provided to persons who were not eligible for medical benefits.

Large cost overruns in the military health-care system prompted Congress to authorize DoD to experiment with a number of alternative health-care programs during the late 1980s and early 1990s. (For details on these programs, see “The Tricare Era in Military Medicine,” October 1994, p. 38.) Those tests led the Defense Department in 1993 to establish Tricare, a managed health-care program comprising twelve joint-service geographical regions within the US. The Pentagon expects Tricare to provide more equitable service, improve its members’ access to care, preserve a choice of medical-care providers, and help contain costs. It incorporates the current CHAMPUS program and some private-sector practices.

DoD published the proposed rule for Tricare in the Federal Register in February 1995, although it had already been negotiating contracts for private-sector health-care services. According to Dr. Stephen C. Joseph, assistant secretary of defense for Health Affairs, who testified before House and Senate committees in March, publication of the final rule this summer should answer questions that had been raised in February.

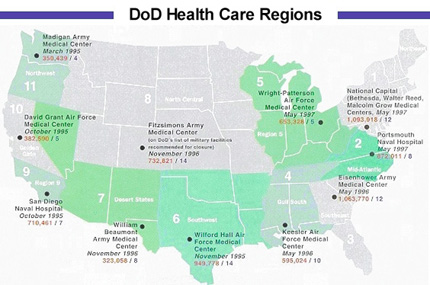

Additionally, DoD will publish some “basic marketing materials” that each of the twelve regions will receive. However, the details of each region’s health-care delivery plan have been left to the “lead agents” of the twelve regions and the commanders of associated military treatment facilities (MTFs). The lead agent for a region is a commander of one of the military medical centers located within the region. The map on p. 6465 shows the regions, lead agents, number of potential beneficiaries, and number of hospitals or medical centers within each region.

Under the Tricare program, regions with large populations of CHAMPUS-eligible beneficiaries will offer a health maintenance organization (HMO) option called Tricare Prime.

|

DoD awarded the first Tricare Prime contract in March, nearly two years after beginning the process. David Baine, GAO’s director of Federal Health-Care Delivery Issues, told Congress on March 28, “So far, DoD’s experience with contracting for private-sector health-care services is proving to be cumbersome, complex, and costly, resulting in contractor protests, schedule delays, and an overall lengthy procurement process.”

Lucrative Contracts

Meanwhile, three contracts have been awarded. The first, covering Region 11 and starting March 1, went to Foundation Health Federal Services, of Rancho Cordova, Calif., for $438.1 million. The second contract, valued at $2.5 billion, was awarded to QualMed, Inc., of Pueblo, Colo., for Regions 9, 10, and 12 with implementation scheduled for October 1. Foundation Health also won the third contract, valued at $1.8 billion, covering Region 6. It goes into force November 1. The last two contracts run for five years.

Dr. Joseph, the Pentagon’s top health-care official, said that, when fully implemented, the Pentagon will have seven fixed-price, at-risk contracts covering the twelve regions. Officials expect to have Tricare Prime operating in all twelve regions by summer 1997.

Since Air Force Magazine first reported details of Tricare in October 1994, the Pentagon has made some changes to Tricare costs and schedules. The system provides an eligible beneficiary with three options. The table on p. 68 (below) outlines the basic costs for each. The map on p. 64-65 (above) shows the current schedule for Tricare implementation in each region.

Tricare Prime. This option is the key to and principal focus of the new health program. Basically, it is an HMO option employing an MTF and a network of civilian health-care providers.

Tricare Prime covers all active-duty members automatically, while others will have to enroll. There is no fee for active-duty dependents, but other eligible beneficiaries will pay an annual enrollment fee up front of $230 per person or $460 per family. Although the fee can be paid quarterly, the payer incurs an additional charge of $5 per payment.

Each individual who enrolls in Tricare Prime chooses a primary-care manager to provide or arrange for his or her health care. The PCM, or someone from the PCM’s team, will treat most ailments and arrange for follow-ups or referrals to specialists. Because access to military facilities may be limited, the standard priority system will continue, providing care first for active-duty members, then their dependents, and finally retirees and their dependents. This system will have the effect of placing some Tricare Prime enrollees with civilian providers. However, those civilian providers will fill out any necessary paperwork.

The Prime option also offers low copayment features, including lower costs than the other two options for inpatient care at a civilian facility. Currently, enrollment is for one year.

Tricare Extra. This second option features a preferred-provider discount of five percent whenever a beneficiary selects a medical provider from the contractor’s network. The beneficiary pays no up-front fee, but he or she does have to pay annual deductibles and make higher copayments than would be the case under the Tricare Prime option. Civilian providers will fill out claims forms for beneficiaries, who will not be forced to use network providers exclusively but instead can elect to use them on a case-by-case basis.

Tricare Standard. The third option is CHAMPUS under a new name. This program allows the greatest freedom in selecting civilian physicians but entails the highest costs. The annual deductible is the same as for Tricare Extra, but both outpatient and inpatient care cost more. Moreover, beneficiaries who receive treatment from a non-CHAMPUS civilian provider must file the necessary paperwork themselves.

Beyond the Tricare Promise

Tricare Prime appears to have the highest potential for providing comprehensive and fairly inexpensive coverage. However, the Pentagon may have to limit the number of applicants it can accept. GAO’s Mr. Baine testified that “DoD expects that availability will be limited, and not all eligible beneficiaries will be permitted to enroll.”

Further complicating matters, he said, is this fact: When it comes to receiving treatment in a military facility, military retirees–even those enrolled in Tricare Prime–will have a lower priority than active-duty dependents who are not enrolled. This means that retirees may have to use civilian providers.

Some even question the Defense Department’s ability to find enough civilian health-care provider networks to cover all twelve areas of the country. If it doesn’t, beneficiaries in those areas will be limited to Tricare Standard.

The ongoing process of base closure and realignment has also caused some uncertainty about continuing availability of military health care. Dr. Joseph said that, in most base-closure areas, the military has created preferred-provider networks for CHAMPUS participants. Additionally, both CHAMPUS- and Medicare-eligible beneficiaries in those areas can participate in either a retail pharmacy network or a mail-in pharmacy program. DoD just expanded the mail-in program to cover ten more Air Force bases and two Army posts. (See “Aerospace World,” July 1995, p. 28.)

Even more worrisome is that DoD’s health-care costs under Tricare may go up. Neil M. Singer, the Congressional Budget Office’s deputy assistant director of the National Security Division, told Congress in March that the effects of Tricare are likely to range between additional costs of about six percent to savings of less than one percent–meaning that the Pentagon will save no more than $100 million and could pay an extra $500 million.

“Based on a range of assumptions about how key factors would affect costs,” said Mr. Singer, “CBO concludes that, if Tricare was fully operational in 1996, the total cost of DoD’s peacetime health-care mission would probably increase by about three percent or about $300 million.”

Of major concern, said CBO, is the lack of control by lead agents. Ostensibly in charge of a region, lead agents will have little real authority over hospital commanders, who will still be controlled by their own service.

DoD plans to incorporate a utilization management program, similar to those found in private-sector managed-care plans, that will include prospective review, concurrent review, discharge planning, case management, and retrospective review. The CBO report pointed out, however, that decisions about use made by a military hospital commander will not be binding on the private contractor.

Additionally, about thirty percent of eligible beneficiaries, some two million people, do not currently use military health care. The existence of this huge “ghost population” has always hampered the Pentagon’s efforts to plan, according to CBO’s Mr. Singer.

The Defense Department estimates that roughly 6.4 million of 8.2 million eligible beneficiaries currently use MTFs. Almost all active-duty members and their families, totaling 4.2 million, use military medical facilities. Only about two-thirds of the three million military retirees and their dependents under age sixty-five use MTFs regularly. About one-third of beneficiaries over age sixty-five, some 1.2 million, regularly use a military health-care facility.

|

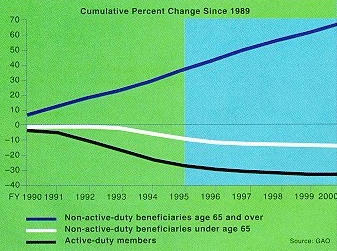

The chart at left shows the projected trend in the beneficiary population through 2000. |

Private-Sector Funding Technique

The Pentagon believes that Tricare will weather these difficulties. This optimism stems in part from use of incentives in funding, which contrasts with DoD’s traditional “historical work load” approach. DoD began using what is called “capitated budgeting” in October 1993 and expects it to help contain health-care costs.

Capitated budgeting essentially allocates a fixed dollar amount on a per capita basis. DoD uses biannual surveys to estimate the number of beneficiaries who will use the military health-care system during a specific period, then determines payment amounts based on that estimated patient pool.

Secretary Joseph said that capitated budgeting “will spark decisions designed to ensure [that] only necessary care is provided and that care will be received in the appropriate setting.” He added that it gives health-care managers “a much improved ability to predict health-care expenditures.”

However, CBO cautioned that DoD’s capitated budgeting method could retain existing inefficiencies because the Pentagon based its per capita rates on past spending levels, which may have been artificially inflated.

At the same time that the Pentagon began developing its Tricare program, Congress directed DoD, through Section 733 of the National Defense Authorization Act of Fiscal 1992 and Fiscal 1993, to analyze the fundamental economic issues bearing on the size of the military medical system. Specifically, Congress wanted to know whether it was cheaper to provide direct medical care to beneficiaries or to reimburse military beneficiaries for care obtained in the private sector.

Wartime Needs Only

After studying the contentious issue for nearly two years, the Pentagon in April 1994 released its report, known as the “733 Study.” Previously, DoD had based the size of its medical establishment on the military’s wartime requirements. During the Cold War, those requirements called for a medical capacity that actually exceeded what it needed to provide day-to-day care for active-duty troops, leaving plenty of capability to care for non-active-duty beneficiaries. Basing its findings on the current strategy of fighting two nearly simultaneous major regional conflicts, the 733 Study found the wartime requirement greatly reduced.

An unclassified summary of the report stated that “medical demands in CONUS [continental US] could be met by about one-third of the 30,000-bed capacity of the MTFs planned to be operating in FY 1999. Similarly, about half of the active-duty physicians projected to be available in FY 1999 would be needed to meet wartime requirements.”

The study pointed out that, if the Pentagon reduces its medical establishment to a size needed for wartime missions, it will also diminish its peacetime capability and force more beneficiaries from the direct-care system into CHAMPUS or Tricare. William J. Lynn, the Pentagon director of Program Analysis and Evaluation who presented the 733 Study to Congress, said that the threshold issue is whether such a shift would reduce or increase DoD health-care costs overall.

The study concluded that MTFs can provide health care “less expensively on a case-by-case basis than can CHAMPUS.” In fact, the study “found a price advantage of ten to twenty-four percent” for a given work load through an MTF as opposed to CHAMPUS. Mr. Lynn attributed this advantage to five factors:

- MTFs provide care in more austere settings than civilian facilities do.

- The military system, with some exceptions, is under less pressure to adopt unproven technologies, thereby slowing the pace of technology-driven cost growth.

- DoD has no financial responsibility when malpractice claims are upheld in court.

- DoD is responsible for almost no indigent care.

- Because military physicians are salaried employees, they have less incentive to prescribe greater amounts of testing and treatment that may be of marginal benefit.

Having noted the potential savings from going to more “in-house” medical care, the 733 Study then switched course and explained how increasing MTF usage would actually raise costs.

With expanded access to the military medical system, it claimed, beneficiaries who had previously chosen not to use DoD health care, whether through an MTF or CHAMPUS, would start to use the system. According to a Rand Corp. study, for every ten patients pulled into MTFs from CHAMPUS, the MTFs would also see about six patients who would have sought care through third-party insurance or would have deferred care entirely–creating a total new work load of sixteen while saving only the costs of the ten from CHAMPUS.

The Rand analysts also found a secondary effect: With expanded opportunity for free MTF care, those who had been using the system would do so more frequently. That would add yet another three cases for every ten pulled from CHAMPUS.

Thus, the total increase would actually be nineteen, not ten–generating what DoD terms “the demand effect”–nearly doubling the original CHAMPUS work load potentially transferred to MTFs. The demand effect would wipe out any cost advantage.

GAO’s Mr. Baine used that same logic to suggest that “an improved health-care benefit option, such as that offered in Tricare Prime, may attract more people than the system can accommodate without increasing total costs.”

He added, however, that the 733 Study was based on data taken largely from a Tricare predecessor, the CHAMPUS Reform Initiative, and that specific projections therefore would “have little direct applicability to the new program.”

So pervasive and heated is the issue of military health care that the Commission on Roles and Missions of the Armed Forces also reviewed the situation. The commission did endorse Tricare “as an important step to a total quality medical program,” but it stated that “Tricare currently does not provide the degree of choice needed to establish a competitive environment that will foster more efficient health care.”

That seems to be the congressional view, as well. At least Congress did ask CBO to study a Tricare alternative featuring the Federal Employees Health Benefit Program. Several groups, including the Commission on Roles and Missions and the National Military Family Association believe FEHB would be less costly and more equitable for beneficiaries.

Evidently, the debate still is wide open. Meanwhile, Tricare marches on.

|

Tricare Options Comparison | |||||||

| Category | Tricare Standard (CHAMPUS) | Tricare Extra | Tricare Prime | ||||

|

Annual Enrollment Fees | |||||||

| Active Duty | $0 | $0 | Automatic enrollment;$0 | ||||

| Active-duty dependents | $0 | $0 | Must enroll;$0 | ||||

| Retirees, military survivors, and dependents | $0 | $0 | Must enroll;$230/ person or $460/ family | ||||

|

Annual Deductibles | |||||||

| E-4 and below | $50/ dependent; $100/ family | $50/ dependent; $100/ family | $0 | ||||

| E-5 and above | $150/ dependent; $300/ family | $150/ dependent; $300/ family | $0 | ||||

| Retirees and dependents | $150/ person; $300/ family | $150/ person; $300/ family | $0 | ||||

|

Outpatient Care at MTF | |||||||

| Active duty | $0 | $0 | $0 | ||||

| Active-duty dependents | $0 | $0 | $0 | ||||

| Retirees and dependents | $0 | $0 | $0 | ||||

|

Outpatient Care at Civilian Doctor | |||||||

| Active-duty E-4 and < dependents | 20% | 15% | $6 | ||||

| Active-duty E-5 and > dependents | 20% | 15% | $12 | ||||

| Retirees and dependents | 25% | 20% | $12 | ||||

|

Inpatient Care at Civilian Hospital (General) | |||||||

| Active-duty dependents | $9.50 | $9.50 | $11 | ||||

| Retirees and dependents | $323/ day + 25% of doctors bill | $250/ day + 20% of doctors bill | $11 | ||||