If it hopes to remain a dominant part of the nation’s military might, the Air Force must reinvent the way it organizes, trains, and equips its fighting forces for combat in a world of rapid change. There is no other option.

That is the conclusion reached by top USAF leaders who addressed the Air Force Association’s annual Air Warfare Symposium, held Feb. 21-22 in Orlando, Fla.

The service’s most senior generals warned that sweeping change is unavoidable. Some of it is under way, and some is still being considered. All are focused on achieving “cross-domain” dominance in air, space, and cyberspace.

Gen. T. Michael Moseley, Chief of Staff, told attendees, “We’re way past refusal speed. We’re committed to this. This is the flight path.”

|

An F-15 (top) and two F-22s soar above the Virginia countryside. (Photo by Rick Llinares) |

The senior USAF leadership urged that the service be allowed to refresh the fleet with new machines and new capabilities, while getting rid of old hardware that no longer meets the nation’s needs. They pushed for streamlined acquisition that will bring on new capabilities faster, and for organizational shifts that will make wartime deployments more seamless than ever.

The leadership also urged that USAF do a better job at advocating for its needs, since both national leaders and the public seem not to grasp the service’s crucial role in national defense.

Moseley used his time at the podium to summarize the new Air Force white paper, a vision statement that “connects the dots” between requirements, capabilities, strategies, and budgets. The new vision document took more than a year to craft and “lays out how we see the future … and what we are going to do about it,” Moseley said.

“I believe we have an opportunity to redefine American airpower,” Moseley said, adding that the opportunity will be lost if the service fails to become more intellectually nimble and adaptive to a future summed up best as “uncertain.”

He pointed to economic globalization, intensified competition for all kinds of resources, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, climate change and rapid technological change as factors all conspiring to create a world “equally complex, if not more,” than that of today, and one requiring an Air Force that is fully capable of handling any air, space, and cyber threat.

Moseley asserted that the service has “140 initiatives” at work aimed at linking strategy to budget and fielding new systems “in a much more timely manner.”

The Organizational Template

For starters, Moseley said, USAF is restructuring itself to make the squadron the “building block of everything,” since USAF typically presents forces to combatant commanders in squadrons.

“The organizational template [when] deployed should be the same as the template at home station,” he asserted. Too often, units deploy to war missions and “somewhere over the Atlantic, some magic fairy dust is sprinkled over the people and the organization, and then you become a theater command structure.” Not anymore, he said.

|

At Balad AB, Iraq, SrA. Rebeca Hill (top) and SrA. Christopher Jaeger perform maintenance on a deployed F-16. (USAF photo by SrA. Julianne Showalter) |

Major commands have been asked to “push … down” their combat headquarters into numbered air forces, since those outfits are typically already organized in line with regional air operations centers, and are configured to match up against joint organizations. This was also the reasoning behind the restructuring of the Air Staff to match up with similar organizations in the Joint Staff, such as A2 for intelligence, organized to mirror the Joint Staff J2.

The Air Force has extended and toughened basic training, with greater focus on the ground combat skills airmen are likely to face when they deploy to Southwest Asia, Moseley noted. He also wants to fill in the gaps that occur in the periods between stints of professional military education to reinforce skills and the warrior “ethos.” He is pushing for greater language training at all levels and plans to expand the opportunities for enlisted as well as officers to obtain advanced degrees.

Moseley acknowledged some USAF missteps that he hopes to rectify. The Air Force has “drifted” in its cultivation of intelligence professionals and selecting them for higher command. As a result, there are no USAF intelligence leaders “in any combatant command.” He said, “We need to do something about it,” and has instructed Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, head of USAF intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, to find a better way.

Similarly, Moseley said USAF’s skills at strategic communications—informing Congress and the American public about USAF’s roles and needs—have atrophied. The Air Force must “be able to tell that story much better than we have in the past.” In the near future, USAF will “reach out” not only to media, but “academia, think tanks, etc.” Moseley said, “We can do better in our communications business.”

The Chief said he’s pursuing 150 initiatives toward Total Force Integration and is moving to ensure that the reserve component is equally involved in all new missions, such as the F-22 and the new tanker.

Moseley plans to merge Red Flag Alaska and Red Flag Nellis to improve combat training opportunities for USAF and allies. He wants to upgrade range threats “as close to fifth generation as we possibly can.”

In acquisition, there’s been some progress in speeding up the delivery of new space systems, and he wants to achieve the same with aircraft. Moseley believes getting a new bomber in service by 2018 is “doable,” if the existing plan is not perturbed.

Summarizing the new vision, Moseley said it gets back to the roots of the Air Force—range and payload, and “to fly and fight” and “to win our country’s wars”—with the new twist of doing it across the domains of air, space, and cyberspace.

|

The F-35, shown during a test flight, is needed to replace old F-16s and other fighter-attack aircraft. (Lockheed Martin photo) |

However, the new vision may not come to fruition if the Air Force can’t trade away obsolete aircraft for new ones appropriate to the threats faced by the nation. So said Gen. John D.W. Corley, head of Air Combat Command.

In a blunt warning, Corley said the US simply must have air dominance, but seems to be losing it.

Aggression, Simply to Survive

“It is a strategic imperative,” he said, and “fundamental to any military strategy. It saves lives, it directly impacts the length of the conflict, as well as the quality of the subsequent peace.” Air dominance allows all other functions of the military to perform their roles, he said.

“We must possess and maintain overmatch, and I would argue … that’s … increasingly at risk,” he said. It isn’t enough that USAF overwhelm the adversary with quality; it must have quantity, too, Corley said.

“Decades-old F-15s, F-16s are now overmatched by newer operational fighters,” he declared. Adversaries around the globe are aggressively pursuing new technologies to erase America’s asymmetric advantage in airpower, and their aircraft aren’t battle-worn.

The “legacy” fleet must fly “more aggressive tactics, simply to survive” against hot new adversary fighters and murderous advanced air defenses. Harder maneuvering puts more stress on old airplanes already tired from 17 years of continuous combat operations. New adversary defenses have greatly expanded range, putting US fighters in danger far away from the target, and putting some targets flat out of reach.

|

Artists’ conception of future bomber by Northrop Grumman (Northrop Grumman illustration) |

“We can’t allow a veiled curtain to be put around targets and not be able to provide our nation and our President options,” Corley insisted.

In fact, the US fighter fleet has decayed so badly that the US “no longer can dictate the time and place and the tempo of modern air warfare,” he asserted. American air dominance is “in doubt for today.”

In the 1980s, the US was technically at peace, but building up to 300 fighters a year, Corley noted. Today, the nation is at war, but is only buying 30 or so fighters a year.

“It’s not a viable strategy,” he maintained.

“History kind of gives us some pretty graphic examples [of] what happens” when a nation doesn’t have air dominance. He added, “We’re way into the red line on the acceptance of risk.”

Corley said last fall’s F-15 crash, which led to a fleetwide grounding for months, was a “wake-up call” that the fighter force’s age can’t be ignored anymore. The F-15’s woes, he said, are “not an isolated incident,” and he noted that F-16s are flying with cracked bulkheads while A-10s need a massive rewinging program to keep them viable.

Given the years of “Band-Aids” and patches put on the airplane to try to keep it going, Corley said stress has been shifted on the F-15 in unknown ways, and he’s had to ask Air Force Materiel Command to test the Eagle to see just how much more it can take.

“For far too long, we have bought way too much risk because we bought too little iron. If we don’t have the iron, we will not have any options,” Corley said.

Time Now an Absent Luxury

He advocates upgrading those aircraft that can endure a while longer, but “ramp … up … existing production lines” of combat aircraft to get them at economical rates, and try not to recapitalize “on the cheap, inside the supplementals.”

|

Artists’ conception of future bomber by Boeing could presage USAF’s 2018 Bomber. (Boeing illustration) |

Air Combat Command is readying a combat air forces strategic master plan that will rationalize the combat fleet with service strategy, and identify the “ends, … ways, [and] … means required to succeed against the threat.” It will also serve as a “master document” that will explain the role of each airman in supporting the wider mission.

New aircraft programs come along so infrequently that the Air Force has lost many of its skills in developing them, Gen. Bruce Carlson, head of Air Force Materiel Command, told the attendees.

Carlson noted that the last time the Air Force had the luxury of trying out an aircraft design and then not using it was in the 1980s, with the F-20 Tigershark. Since then, “there’s just no room for error,” Carlson said. Each program has become too precious, and “must succeed,” because “we’re only going to get one or maybe two per decade.”

That’s not healthy, he said, and the result is that there’s a steadily decreasing pool of expertise, “financial resources, [and] political support” for new aircraft. Moreover, the industrial base is no longer robust enough to permit trying out a number of concepts and choosing one that works best.

It’s a deficit in what’s called “developmental planning,” Carlson said, and encompasses a broad array of disciplines from threat assessment—not just at the outset, but at initial fielding and every decade after that—to maintenance innovation.

The pressure to keep the few approved programs on track is great. Programs find themselves being pushed forward before they are technologically ready to proceed, with the result that AFMC has sometimes been “unable to deliver” when expected. Moreover, the political process is totally unforgiving of any missteps, he said.

“There are fewer dollars, fewer new starts, and our aircraft are flying longer,” meaning there are very few opportunities for engineers to gain experience in developing aircraft, Carlson noted.

“It will take some time to rebuild” USAF’s expertise in this area, he said. “We simply can’t do it overnight.”

Programs will work better, he said, if more attention is paid up front to life cycle costs, requirements, and technical maturity.

Healthy aircraft development is not just a matter of time, Carlson emphasized. He pointed out that Russia started its F-22 equivalent program in the late 1990s, and said it will fly the aircraft, called the T-50, in 2012 and enter production in 2015. He believes Russia will “hold to” that schedule.

“So, it’s possible to do this, and do it in a shorter time frame than we do,” he observed.

Carlson also warned that the US is experiencing a brain drain, and that foreign students who come and take advantage of America’s excellent education system return home and are “leveling the playing field” by developing technology equal to our own.

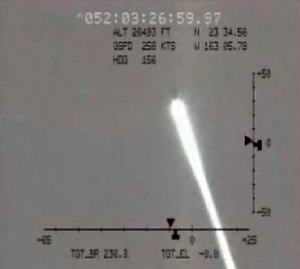

|

Two Navy images capture the missile shot and destruction of a defunct spy satellite in February. USAF Gen. Kevin Chilton, commander of US Strategic Command, led the shootdown operation. |

|

The US lead in “propulsion, in metals, in nanotechnologies … has decreased significantly, and it’s decreasing at an ever-increasing rate,” he cautioned.

AFMC is in the midst of a debate to determine its new philosophy about how airplanes are maintained. In the 1970s, Carlson said, the Air Force’s idea was called “safe life,” and it mandated that every part on the airplane be perfect through a predicted lifespan. However, once that age was reached, it grounded them.

The Air Force then went to an inspection regime, in which it would inspect parts, replace them, and send the aircraft back up to fly. He said the air logistics centers, when asked, will dutifully agree that they can keep practically any machine flying, no matter how old. However, that doesn’t address the issue of operational obsolescence, and becomes a liability when the service is trying to argue for more modern equipment. So, the inspection regime is being rethought, Carlson said.

Despite the challenges, AFMC has had some big successes in recent years, such as fielding the MQ-9 Reaper and Small Diameter Bomb well ahead of schedule, and getting the ROVER system into the hands of the troops, Carlson said. He believes that, with the right levels of support, AFMC will be able to do as well in the future.

Cross-Domain Domination

Gen. C. Robert Kehler, head of Air Force Space Command, echoed Moseley’s remarks, saying that USAF is no longer supported by space and cyber capabilities, but is now “all about cross-domain integration.”

Since space assets operate in both space and cyberspace, and aircraft operate in air and cyberspace, it’s “critically important … how we put those three domains together to fly, fight, and win,” Kehler said. Space Command is working to unify its efforts across all three.

Kehler believes that space capability has come to be taken for granted, as an always-on 365-day utility that no one pays much attention to unless it isn’t working.

Space is an inherent part of everything the US military does, he asserted. If the nation were to lose a significant chunk of its space capability, it would be like going “back in time,” Kehler suggested; the US would still be able to fight, but it would require far more assets, funds, and “far more casualties.”

He said that the Air Force doesn’t get “the credit that we deserve for the national and … international mission that we perform,” to include global positioning navigation, weather, communications, space surveillance, and a wide range of other missions. He wants a better effort at conveying to the public and the rest of the national security community “what it is that the United States Air Force does.”

“None of our space capabilities ever are down for a week or two … while we modernize,” he said. That’s like changing a TV from analog to digital “while the TV’s on.” If ever a space asset is offline even shortly, the joint community is “on your case about, ‘where are you?’ “

|

An MQ-9 prepares to launch from Creech AFB, Nev. Gen. Bruce Carlson, AFMC commander, says the Air Force must strive for rapid developments of the sort that fielded the Reaper. (USAF photo by Lawrence Crespo) |

In short, Kehler summarized, “we don’t have the luxury” of not providing expected capabilities for the military, nation, or the world.

Kehler believes that “we have turned the corner on the worst of our acquisition issues,” and while “we … still have problems to solve,” Air Force Space Command is setting records for successful launches and years of on-orbit operations “without a premature failure.”

However, “as we look to the future, we’re going to have to come to grips with a new way of developing and deploying space capability,” because the current system “takes us too long” to put new capabilities in orbit. He pointed to the ability to quickly launch satellites, and the use of smaller satellites, as two ways to approach this requirement. “Tacsats” won’t last as long as big ones, but will cost less, can be fielded in larger constellations, and can be refreshed more rapidly.

| The View From US Strategic Command

The February shootdown of a derelict reconnaissance satellite was a historic first because it marked the first operation in which US Strategic Command was the supported entity, its chief, Gen. Kevin P. Chilton, told the AFA symposium. “Our space forces are normally in support of other regional combat commanders,” Chilton said. “In this case, we needed support from regional [and functional combatant commanders] as well, to pull this off.” A Navy cruiser fired a specially modified Standard missile to break up the satellite while still in space, because it was feared that the spacecraft’s hydrazine propellant tank would survive re-entry and pose a hazard to people on the ground. Chilton said STRATCOM got everything it needed from US Pacific Command, Air Force Space Command, the National Reconnaissance Office, NASA, the State Department, the Missile Defense Agency, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, US Transportation Command, and others for the highly successful mission. There was never any question over who was in charge, nor any hesitation to support the operation, Chilton said. The effort showed that STRATCOM has it “about right” in how it is addressing its missions and capabilities. Chilton is charged with eight missions, but focuses on three: “space, cyberspace, and strategic deterrence.” He puts those first because they are the ones in which STRATCOM actually has forces assigned and for which it is the logical focal point for execution. STRATCOM has intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance responsibilities, but this is chiefly in the area of apportioning “very limited ISR resources, to find better ways that we can share” air-breathing, space-based, and seaborne capabilities. Chilton insisted there be no letup in fielding the next generation of early warning systems. The nation “cannot tolerate a gap in missile warning from space,” he said, nor can it bear an interruption of ISR services from space. “We shouldn’t have continuing discussions on this,” he said. By now, it ought to be understood as the right thing to do, “and we just move on and make it happen.” Chilton also pushed for the restoration of an ability to build and test nuclear warheads. Within 40 years, he said, the plutonium in the warheads in America’s nuclear arsenal will decay to the point where the weapons may not work properly. Meanwhile, the people with the expertise to do such work have nearly all retired. He advocated making new warheads of a configuration making them useless if stolen by terrorists. He also argued for developing a new, nonexplosive way to test the weapons and ensure their safety, reliability, and effectiveness. “We cannot do that today in our Cold War-era weapons,” he said. To maintain a level of 2,000 warheads at a 40-year replacement rate, the US would have to start immediately building new ones at rate of 50 per year, Chilton noted. If the US fails to keep its nuclear warheads credible, nations under the US nuclear umbrella might feel compelled to develop their own, and proliferation would ensue, he argued. “No one has to stand up and clap on this one, but I’m telling you folks, we’ve got to get on with this. This is a problem that we need to invest in and focus on today.” |