During the early years of the Cold War, the United States developed and fielded a hydrogen bomb in the face of repeated military and political provocations by the Soviet Union. The explosion of a Soviet atomic device in 1949, in fact, gave major impetus to the US hydrogen bomb project.

A decision on whether to proceed with a thermonuclear bomb required the US to push the envelope of nuclear technology while memory of the atomic bomb attacks that ended World War II was still fresh. What resulted was a heated controversy among scientists, politicians, the military, and governmental officials ending in President Harry S. Truman’s landmark January 1950 decision to proceed.

|

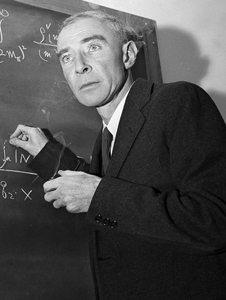

J. Robert Oppenheimer at Princeton University. |

The United States came out of World War II in sole possession of the atomic bomb, but it was rapidly demobilizing. The push to “bring the boys back home” reduced the US military from a wartime peak of 12 million to only two million in uniform by July 1946.

The Soviet Union was already casting a shadow over the postwar world. Despite massive wartime material and manpower losses, it had the largest army in the world, and countries in Eastern Europe were being turned into Soviet satellites.

In a historic speech in February 1946, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin declared that there could be no collaboration between communist countries and “the dying, corrupt” capitalist democracies. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas called Stalin’s speech a “declaration of World War III,” while British Prime Minister Winston Churchill warned that an “iron curtain” was descending across Europe, dividing East from West.

In February 1948, the communist coup in Czechoslovakia sent what Truman called “a shock throughout the civilized world.” Then, in June, the Soviets blocked access to Berlin, sealing off land and water routes, threatening two million Berliners with starvation.

In response, the US and Britain organized the Berlin Airlift and Truman approved the movement of non-nuclear Air Force B-29s to the United Kingdom.

Because of these and many other instances of hostility, the US made the decision to build a long-range atomic deterrent force. That decision would actually pose fewer difficulties than the question of whether to develop a thermonuclear bomb.

Truman, a hard-money man, had Defense Secretary Louis A. Johnson reign in defense spending. In conjunction with the Berlin Airlift and the onset of the Cold War, Johnson’s tight-fisted budgets in 1948-49 aggravated an already tense roles and missions confrontation between the Air Force and Navy over the atomic mission.

In China, meanwhile, the communists of Mao Zedong had triumphed and driven the Nationalist government to Taiwan. The Alger Hiss trials revealed accusations that a high State Department official had passed government documents to a Soviet agent.

Into this dangerous world of limited resources and Soviet provocation came a world-changing event. On Sept. 3, 1949, an Air Force WB-29, flying east of Russia’s Kamchatka peninsula, collected a radioactive air sample.

After additional flights, USAF’s Long-Range Detection Division informed the Atomic Energy Commission of its findings. The AEC convened a panel headed by Vannevar Bush with J. Robert Oppenheimer, who during World War II had been instrumental in developing the atomic bomb. The AEC panel concluded that the air samples carried products of nuclear fission consistent with an atomic explosion in the Soviet Union in late August 1949.

End of a Monopoly

Informed scientific opinion in the United States had predicted that a Soviet atomic bomb was years away, but the USSR already had the bomb.

Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg, Air Force Chief of Staff, informed Truman of the Soviet atomic explosion. At the urging of the Joint Chiefs, Truman announced on Sept. 23 that the Soviets had exploded an atomic bomb, ending the American nuclear monopoly.

The Administration’s austere defense funding continued even in the wake of the Soviet atomic explosion—despite increasing pressure from Congress and the public. Johnson continued to trim the defense budget for Fiscal Year 1950.

The path to initiating a concerted thermonuclear program remained difficult and controversial. The scientific community was divided about whether to proceed, with many leading scientists opposing an H-bomb project. The controversy became the postwar intersection of science and politics, setting up a tense atmosphere of scientist against scientist.

Theoretical work on the possibility of a thermonuclear reaction—a fusion of small nuclei into larger units, the opposite of fission—began in the US in the 1930s. An expatriate Russian, George Gamow, and Hungarian-born theoretical physicist Edward Teller studied thermonuclear problems centering on the lightest of elements, hydrogen.

Also in the late 1930s, fission was discovered and the possibility of an atomic bomb became a reality. On Aug. 2, 1939, Albert Einstein wrote President Roosevelt, noting the possibility of building a bomb of enormous power from uranium.

In early 1942, a group of theoretical physicists recruited by Oppenheimer at the Radiation Laboratory of the University of California Berkeley studied the thermonuclear problem. They simultaneously developed the atomic bomb and probed the question of whether nuclei of deuterium, or heavy hydrogen, could be exploded. These physicists became convinced that a thermonuclear explosion could be accomplished.

|

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, President Harry Truman, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the Potsdam Conference in 1945. |

This work led to Los Alamos National Laboratory’s creation in 1943, under Oppenheimer’s direction. Oppenheimer was instrumental in the laboratory’s founding and he and Teller led the recruitment of scientists to work there. Some small thermonuclear research continued but was clearly secondary to the immediate, intensive work on the atomic bomb—the Manhattan Project, headed by Maj. Gen. Leslie R. Groves.

After the war, many of the physicists left Los Alamos, refusing to work on a hydrogen bomb. Some thought the US had no need for a thermonuclear weapon, others felt the Soviet Union was many years from developing their own nuclear weapons.

In any event, there was little support for development of a thermonuclear bomb in the years just after World War II. Then came the Soviet nuclear blast, and much changed right away.

The AEC’s General Advisory Committee, headed by Oppenheimer, convened to consider whether to develop a thermonuclear bomb. The AEC’s GAC had been created in December 1946 to advise the AEC “on scientific and technical matters relating to materials production and research and development.”

The committee unanimously recommended against developing a hydrogen bomb, a decision also supported by three out of five members of the AEC.

“We all hope that by one means or another, the development of these weapons can be avoided,” the report stated. “We are all reluctant to see the United States take the initiative in precipitating this development.” The committee noted, “The extreme dangers to mankind inherent in the proposal wholly outweigh any military advantage that could come from this development.”

A minority report, curiously similar to the majority, signed by Enrico Fermi and Isidore I. Rabi, argued that the H-bomb presented a danger to humanity. It was important for the President “to tell the American public and the world that we think it wrong on fundamental ethical principles to initiate a program of development of such a weapon,” it read.

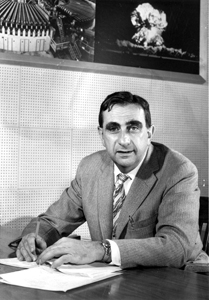

“I am convinced that if, after Hiroshima, men of Oppenheimer’s stature had lent their moral support—not their active participation, but only their moral support—to the thermonuclear effort, the United States would have shaved four years from the time it took this country to develop a superbomb,” wrote Teller, who would come to be known as the father of the hydrogen bomb, in his memoir.

There Is No Choice

Following the GAC meeting, but unaware of its formal report, Teller, anxious to tackle the theoretical and engineering intricacies of developing the H-bomb, met with Sen. Brien McMahon, chairman of the Congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy. Teller emphasized that proceeding with development was important to the nation’s security.

“There was no way to assess the military implications of thermonuclear weapons without knowing more about them,” he argued, and McMahon agreed.

Vandenberg testified to McMahon’s committee that the superbomb would make the strategic deterrent more effective, becoming the major weapon in the arsenal of Strategic Air Command.

The scientists at Los Alamos needed approval from the top, however. McMahon, AEC commissioners Lewis Strauss and Gordon Dean, and other members of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy urged Truman to proceed. Strauss proposed “an intensive effort to get ahead [of the Soviets] with the super[bomb].”

The Joint Chiefs made the case to Truman that the hydrogen bomb “would improve our defense in its broadest sense, as a potential offensive weapon, a possible deterrent to war, a potential retaliatory weapon, as well as a defensive weapon against enemy forces.”

Truman then formed a special committee of the National Security Council with Secretary of State Dean Acheson; Johnson; and AEC chairman David E. Lilienthal. This committee recommended that work on the hydrogen bomb proceed with a concurrent re-examination of US foreign and defense policies.

At a committee meeting on Jan. 31, 1950, Truman asked: “Can the Russians do it?” All agreed that they could. Truman replied, “We have no choice, we’ll go ahead.”

The same day, he publicly directed the AEC to develop the hydrogen bomb. “It is part of my responsibility as Commander in Chief of the armed forces,” Truman stated, “to see to it that our country is able to defend itself against any possible aggressor. Accordingly, I have directed the Atomic Energy Commission to continue its work on all forms of atomic weapons, including the so-called hydrogen or superbomb.”

|

Edward Teller, in 1958, as director of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. |

The detonation of the Soviet atomic device had been foremost in Truman’s decision. Then, within a few days of Truman’s announcement, it was revealed in London that physicist Klaus Fuchs, a member of the British Mission at Los Alamos, had been passing atomic bomb data to the Soviets since 1941.

“Atomic bombs in our possession had seemed absolute weapons,” Teller said. “Atomic weapons on both sides now seemed to herald absolute uncertainty.” Even if the US failed to develop a hydrogen bomb, the Soviets might well build one.

Truman, however, wanted a long-range reassessment that integrated foreign and defense policies into an effective national security program, putting economic and military objectives in priority order. With this in mind, concomitant with the hydrogen bomb decision, he directed a re-examination of foreign policy and strategic planning in light of the Soviets’ “probable fission bomb capability and possible thermonuclear bomb capability.”

Acheson and his policy planning chief, Paul H. Nitze, headed the State-Defense team that structured the document that became known as NSC-68. It was submitted to Truman in early April 1950 and was still being studied when the Korean War erupted in June 1950. NSC-68 stated a basic incompatibility between the political systems of the US and USSR and recommended a massive defense buildup—including development of a hydrogen superbomb.

NSC-68 estimated that the Soviet stockpile would increase from 20 atomic bombs in mid-1950 to approximately 200 by 1954.

This would bring about an atomic stalemate, while the Soviets maintained their conventional war superiority. “The actual and potential capabilities of the United States … will become less and less effective as a war deterrent,” the seminal document stated. The US would have to maintain “the capability of conducting powerful offensive air operations against vital elements of the Soviet war-making capacity.” NSC-68 failed to make specific cost estimates but emphasized that increased defense expenditures were justified due to the critical nature of the threat.

Meanwhile, the Joint Chiefs had recommended “immediate implementation of all-out development of hydrogen bombs and means for their production and delivery.”

In March 1950 ,Truman gave H-bomb research the highest priority.

The developmental challenges were severe. It had yet to be demonstrated that a hydrogen bomb—a quantum jump in nuclear technology—was technically feasible. As Truman described the situation, “Everything pertaining to the hydrogen bomb was … still in the realm of the uncertain.”

First, But Just Barely

There were other difficulties as well. An all-out H-bomb effort would slow the building of the atomic stockpile and divert critical Uranium-235 resources. Above all, the question remained: Would the hydrogen fusion process work

The answer was not long in coming.

|

SAC B-36s on a training mission during the Cold War. The decision to build a long-range deterrence force was easier than deciding to proceed with the H-bomb. |

At Los Alamos, Teller and Stanislaw Ulam evolved a design that featured a fission bomb trigger staged with fusion fuel—nuclear fusion resulted from a radiation implosion compressing and igniting the fusion field. This Teller-Ulam trigger design opened the way for development and production of the hydrogen bomb.

At Princeton University, John von Neumann had led the computer calculations for the project, which was extremely important to the Los Alamos hydrogen project.

The first hydrogen bomb was exploded in the “Mike” test at Eniwetok atoll in the South Pacific on Nov. 1, 1952. Teller had left the Los Alamos laboratory and returned to the University of Chicago, and was invited to watch the explosion, generating the equivalant of 10.4 million tons of TNT, at the seismograph at the University of California Berkeley.

“I believe that everyone who was closely or distantly connected with this effort—along with those who have made subsequent contributions—was driven by the knowledge that the work was necessary for the safety of our country,” he said.

Teller then supported the opening of a second laboratory—opposed by Oppenheimer—which subsequently was established at Livermore, California.

Physicist Harold Brown joined the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory when it opened, became its third director, and in 1965 was named Air Force Secretary. At Livermore, Brown led the drive to improve the effectiveness of thermonuclear weapons in cost, yield, and weight.

The hydrogen bomb was successfully developed despite the opposition of many in the scientific community—Oppenheimer, Fermi, and Einstein among them. These scientists opposed the H-bomb project primarily on moral grounds.

Teller himself became a controversial figure, some scientists arguing that his fixation with developing a megaton-yield device—rather than a high-kiloton yield—actually slowed development of the H-bomb. In 1954, Oppenheimer ignited another controversy when, after an AEC hearing, his security clearance was revoked due to his associations with members of the Communist Party.

|

The first hydrogen bomb exploded at Eniwetok atoll in 1952. It generated the equivalant of 10.4 million tons of TNT. |

The importance of the H-bomb decision was made manifest when in August 1953—just nine months after the first US hydrogen explosion—the Soviet Union announced its own thermonuclear explosion and then conducted its first major hydrogen bomb test in November 1955.

Truman’s final decision to go ahead with the H-bomb project showed that the nation was prepared to do whatever it thought necessary to preserve the US edge in strategic nuclear deterrence during the Cold War.