Air Force officers who run big regional commands are rare birds indeed. In Europe, for example, there have been only two—Gen. Lauris Norstad, who served as the Supreme Allied Commander Europe during the period 1956-62, and Gen. Joseph W. Ralston, who held the same post from 2000 to 2003.

In fact, the only other regional command ever to be headed by an Air Force officer is US Northern Command, created after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks here. Two of its commanders—Gen. Ralph E. Eberhart (2002-04) and Gen. Victor E. Renuart Jr. (2007-present)—have been airmen.

Other than that—zip.

US Pacific Command, dating to 1947, has been led by 21 admirals but zero officers from the Air Force (or any other armed service). US Central Command, established in 1983, has had nine commanders, all from the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps. Not one of US Southern Command’s 30 commanders has been an airman. The newest regional entity, US Africa Command, drew its first commander from the Army.

|

Gen. Joseph Ralston, then Supreme Allied Commander Europe, leaves a meeting in Skopje, Macedonia. (Photo by Boris Grdanoski, Reuters/Corbis) |

True, Air Force officers today lead both US Strategic Command and US Transportation Command. In the recent past, airmen have commanded both US Special Operations Command and US Joint Forces Command. Airmen have also had their fair share of rotations as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, from Gen. Nathan F. Twining (1957-60) through Gen. Richard B. Myers (2001-05).

Still, with regional combatant commands growing in importance, there’s a sense that airmen have been overlooked and perhaps even slighted. If airpower is the dominant force in today’s military operations—and it is—you would expect to see more airmen in command. Why are they not

The first thing to say is that the record cannot be an accident of history; the numbers are too stark. Indeed, notes the airpower historian Phillip S. Meilinger, “The statistics are stunning.”

The birth of the unified command system roughly coincided with the birth of the Air Force, so random selection would have led to roughly equal numbers of commanders among the services. As Meilinger (a retired Air Force colonel) totes up the score, there have been 110 theater commanders since World War II, counting the four-star joint commanders on the Korean Peninsula and in the Vietnam and Iraq wars.

The Air Force has supplied only the four mentioned—Norstad, Ralston, Eberhart, and Renuart. The Army has been the overwhelmingly dominant service, supplying 75 of those 110 joint commanders. The Navy has produced 25 of them, most of them in the Pacific. Even the Marine Corps has outpaced the Air Force, providing six regional commanders, according to data prepared by Meilinger.

|

Gen. Lauris Norstad is one of only two airmen to serve as the Supreme Allied Commander Europe. |

When it comes to non-geographic-theater four-star command billets, USAF’s record has been better, but only marginally. USAF has supplied commanders in 21 of 71 of these cases. (On Oct. 7, 1999, Atlantic Command became US Joint Forces Command and its mission switched from geographic to functional responsibilities.) Even so, the Navy significantly surpasses the Air Force in this category of command, with 30 commanders.

Experts have cited a large number of possible reasons for the paucity of airmen serving in theater command. The list begins with the peculiarities of the Air Force as an institution and extends to the US military’s stunted view of airpower, politics of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Pentagon’s nomination and Congressional confirmation processes.

To begin with, it seems reasonably clear that, for a long time, the Air Force did not place much emphasis on the leadership of regional commands. As Meilinger described the state of mind at the time, “The epitome for airmen was to be Chief or ACC [Air Combat Command] commander.” Everything else, he went on, was “table crumbs.”

Throughout the long Cold War, USAF’s mission was focused tightly on nuclear deterrence underwritten by heavy bombers. Air Force generals had a lock on the awesome power of Strategic Air Command, a “specified” or single-service command. Over its 46-year existence, SAC had a total of 13 commanders. From George C. Kenney in 1946 through Curtis E. LeMay and Russell E. Dougherty and all the way to George Lee Butler in 1992, all wore Air Force blue.

A Transformation

Until fairly recently, moreover, ostensibly “unified” regional commands were in reality dominated by the doctrine and preferences of the single service which served as the principal supplier of forces to the region. In Europe and the Americas, it was the Army. In the Pacific, that was the Navy. In the Middle East, it was the Marine Corps as well as the Army.

In the relative quiet of the late Cold War, the CINC job was not popular because it would keep a top officer away from his military branch and its own forces. Power, by and large, rested with the services. In that framework, it was better for an airman to command Strategic Air Command or Tactical Air Command than to take over largely administrative and diplomatic duties in some distant geographic theater.

Then came three transformative developments. They were:

|

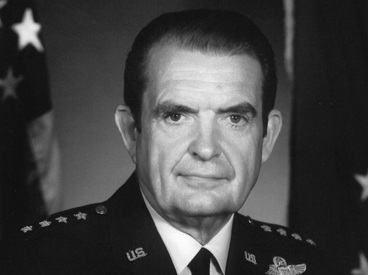

USAF Gen. Nathan Twining, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1957-60. |

The Goldwater-Nichols Act. Signed into law in October 1986, Goldwater-Nichols altered the national chain of command so that combatant commanders had direct authority over forces in their area of operations. Instead of Army, Navy, and Air Force components planning and directing their own operations, combatant commanders now had the whip hand. The combatant commander, in turn, reported not to his own service branch but rather to the Secretary of Defense, who is in fact the immediate superior of the combatant commander. In practice, the reporting is by custom done via the JCS Chairman, who has an advisory role.

The Gulf War. Desert Storm in 1991 demonstrated, in spades, the new power and prestige of a regional commander. The war made a global superstar of a once-obscure Army officer—Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf. When he assumed leadership of CENTCOM, Schwarzkopf felt as though he had “stumbled upon a neglected frontier,” he later wrote. He was also brutally frank about how he got the job. “Central Command had traditionally alternated between the Army and the Marine Corps, and since the current commander, Gen. George Crist, was a marine, his successor would almost certainly be the man [the Army Chief of Staff] chose.” He was that man. Victory in the Gulf propelled Schwarzkopf and the CENTCOM post into the spotlight. The combination of rapid victory and global media surrounded Schwarzkopf with glamour not seen since the days of Eisenhower and MacArthur.

The rise of regional policy. After the troops left the Gulf region, the US and several allies stayed behind to maintain no-fly zones in the southern and northern portions of Iraq. For 12 years, CENTCOM contained Iraqi power from the air while, to a less important degree, Navy warships enforced sanctions at sea. However, the command continued to alternate between the Army and the Marine Corps. The strangeness of ground-force specialists commanding an air and maritime theater led some to question why Air Force generals were not considered for this top regional post.

It was against this backdrop that the absence of USAF generals in command began to stand out. It seemed that airpower was being left out of the big game in town.

All of the three factors, but especially the accent on regional policy in the post-Cold War world, turned the combatant commanders into important players in defense policy. Suddenly, emphasis was on partnerships and alliances. Regional commanders found themselves at the leading edge of cooperative engagement, larger military training enterprises, and so forth.

|

USAF Gen. George Brown, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1974-78. |

Back in Washington, policy-makers, in turn, were listening more closely to the views of regional commanders. What they had to say had new weight in the reformulation of defense strategy and plans. The mid-1990s saw new emphasis on joint doctrine and joint vision statements, with impact on service actions.

Some argued that the regional commanders should have a stronger voice in the Pentagon’s planning, programs, and budget deliberations. Those commanders had long been generating annual integrated priority lists, naming the top new systems desired by their commands, but the lists always had gotten polite brush-offs. Now, some wanted to give the combatant commanders real and significant influence over resources, at the expense of the services’ “organize, train, and equip” powers.

This raised a troubling question: If regional commanders were to have a bigger role in requirements, and none of them were airmen, who would convey USAF’s perspective

In July 2000, Air University’s College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education published a paper titled, “Once in a Blue Moon: Airmen in Theater Command,” written by Air Force Lt. Col. Howard D. Belote. Belote’s study located the problem in the fact (as he saw it) that “airmen appear to have a narrower upbringing and less exposure to the political process than other service members.” Further, Belote’s research suggested that Army and Navy commanders tended to log numerous assignments within the theaters in which they eventually commanded.

Belote based his conclusion, in part, on the declared views of one Richard B. Cheney, then a former Secretary of Defense but not yet a United States vice president. In an interview with Belote, Cheney contended that the Army and Navy tended to have placed in the command queue many officers “who’ve worked their way up” in a specific theater. The Air Force had not.

|

USAF Gen. David Jones, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1978-82. |

Tradition obviously factored heavily into selections, and the Air Force wasn’t the only service to get shortchanged. United States Southern Command seemed to have been locked in for the Army from 1963, when it became a four-star command. The thinking was that most militaries in the region were run by soldiers, so the US should also send an Army man to deal with them and tighten the links with foreign officers. That concept changed only in 1997 with the appointment of a Marine Corps general to lead the command. Still, while the post now has been held by soldiers, sailors, and marines, it has never gone to an airman.

The Navy Hold

The appointment of Air Force Gen. Joseph W. Ralston as Supreme Allied Commander Europe was a headline-making event. Ralston took over for Army Gen. Wesley K. Clark, who had fallen out of favor in the wake of Operation Allied Force, the 1999 NATO combat operation in Serbia. Ralston’s appointment marked the first time since 1963 that an airman had headed up a big regional command.

Ralston’s career at first glance seemed to run counter to advice on how to build a regional combatant commander. A fighter pilot with extensive Vietnam experience, Ralston held a number of command jobs within the Air Force and spent significant amounts of time on the staff in research, development, and acquisition. He attended Army Command and General Staff College and later the National War College, but these were his only assignments outside the Air Force until he became vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1996.

Ralston was considered for nomination as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He withdrew his name amid reports that he had engaged in an extramarital affair years before, when he had been legally separated from his wife. Army Gen. Henry H. Shelton was selected, making it three in a row for the Army.

In reality, though, Ralston had just the right resume for the European post. His combat credentials and staff experience were well-matched by in-depth assignments in research and development of new technologies—an especially important factor in the European Theater. Most important, Ralston during his years as vice chairman had earned the confidence of the Joint Chiefs and the Pentagon leadership.

|

USAF Gen. Richard Myers, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2001-05. |

Even with the Cold War over, the SACEUR job was the crown jewel of theater commands. Ralston served ably until retirement in 2003. However, the next attempt to appoint an airman to a major regional command did not fare so well.

This time around, Pentagon leaders nominated an airman, Gen. Gregory S. Martin, to succeed retiring Adm. Thomas B. Fargo as the leader of Pacific Command. In the end, though, it was clear that neither Goldwater-Nichols nor any other mortal force could blast the Navy out of that chair.

We now know that emotion and tradition have conspired to give the Navy a lock on that command. In the service’s historical narrative, the US fleet and aviators turned the tide of World War II in the Pacific. Since then, the emotional attachment to the command at Pearl Harbor has scarcely dimmed. There is a logic to keeping such a large maritime theater in Navy hands, yet similar logic has been discounted in other commands. For example, Navy and Marine Corps officers take turns with USAF officers at the helm of US Strategic Command, the lineal descendent of USAF-dominated SAC.

In summer 2004, Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld tried to break the Navy hold on the Pacific. Known for scrutinizing all service nominees for key posts, Rumsfeld also had shown himself willing to reject service nominees for joint or senior service billets, often running through several names before settling on a candidate. Those in charge of guiding senior officer career moves learned to expect major churn from Rumsfeld.

So, with Fargo edging toward the door and with senior admirals speculating which of their number would wind up at Pearl Harbor, Rumsfeld unexpectedly nominated Martin, a stellar Air Force officer, to take the top Pacific job.

When it happened, a PACOM public affairs officer issued to Stars and Stripes a remarkably bland statement: “US Pacific Command is like all joint commands. It can be commanded by qualified officers from any service.” For his part, Fargo praised Martin as “a superb officer.”

Privately, however, the Navy was shocked senseless. More to the point, the same was true of senior members of the Senate and House. One of the shockees was Sen. John S. McCain (R-Ariz.), a retired Navy officer who had served in the Pacific and was a POW in Vietnam. McCain’s father, Adm. John S. McCain Jr., had been PACOM commander in the years 1968-72.

The stage was set for confrontation. It came during an October hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee on whether to confirm Martin in the Pacific post. Although officers called to testify must swear to speak truthfully and candidly, Martin’s hearing turned into a minefield.

Senate questions submitted in advance to Martin had concentrated heavily on topics of interest in the Pacific. In the hearing, however, McCain bore in on Martin about former Air Force acquisition executive Darleen A. Druyun, who had been convicted of contracting favoritism and ultimately served jail time. Martin said he had seen “nothing inappropriate” when he worked with her several years before. McCain angrily declared, “I’m questioning your qualifications for commands.”

It was an oily insult to one of the US military’s premier officers, but Martin gracefully withdrew his nomination, stating, “I believe it in the best interests of the Pacific Command and the Air Force Materiel Command [Martin’s venue at the time] for me to withdraw my nomination, even though I have not been involved with the KC-767 tanker program.”

Get In the Game

Adm. William J. Fallon was summoned from his post at the Navy’s Fleet Forces Command in Norfolk, Va., to take over the now open post in the Pacific.

McCain’s disruption of the Martin nomination marked the start of a retrenchment for the Air Force. In March 2007, Fallon was selected to move from the Pacific to take the helm of Central Command in the Mideast. The surprise move ended 24 years of Army and Marine Corps leadership of CENTCOM. Clearly, there was no prejudice about handing command to a Navy man. It appears that no one from the Air Force was even seriously considered.

Not long afterward, retirement opened up the top post at Southern Command. This prize, too, went to the Navy.

Whether the reasons are personal or institutional or both, the Air Force has long been underrepresented in top command jobs. The disparity matters more than ever as the regional commands become a focus of defense strategy. At the least, the airmen’s perspective is likely to be given short shrift.

|

Then-Lt. Gen. Charles Horner (l) and Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf speak at a press conference in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, during the first Gulf War. (Photo by Jacques Langevin, Corbis Sygma) |

It seems undeniable that the pattern must change—if not immediately, then reasonably soon. As Belote said, “If … airpower is to have the game ball, should not someone who has devoted a career to airpower quarterback some of the games?”

Three transformations are vital.

First, the Air Force must groom its leading generals for command positions. Today that means not only staff assignments but tours where Air Force officers gain credibility as warriors. As Belote’s study pointed out, understanding ground operations—which have dominated US military thought—is also essential. The recent experiences of airmen in Iraq and Afghanistan should go far toward broadening the base of air and space warriors armed with outstanding joint skills.

Second, the airman seeking a top combatant command must catch the eye of those in the political process. At all costs, the Air Force should guard against running its promotion process based on “political acceptability,” counseled one retired Air Force four-star. At the same time, the record bears out a need for acclimating prime candidates to circles outside of the Air Force. Sending forward the best candidates demands a blend of experience on top of the excellence that got the officer to three stars in the first place.

Third, all evidence is that the institutional Air Force needs to find a way to fight harder or politic better for those general officers whose names do go forward. “We need to do a far better job in the political arena fighting for our people,” said Meilinger. “We seem not to want to dirty our hands with the political process, and we pay for that seeming fastidiousness.”

Rebecca Grant is a contributing editor of Air Force Magazine. She is president of IRIS Independent Research in Washington, D.C., and has worked for RAND, the Secretary of the Air Force, and the Chief of Staff of the Air Force. Grant is a fellow of the Eaker Institute for Aerospace Concepts, the public policy and research arm of the Air Force Association. Her most recent article, “The Long Arm of the US Strategic Bombing Survey,” appeared in the February issue.