When the report was first released, two months after the close of World War II, Time magazine did not hold back. “Awesome and Frightful” read the headline on its Nov. 5, 1945 story. It was, in Time’s estimation, “the definitive source on man’s inhumanity to man, pre-atomic style.”

Gen. Carl A. Spaatz, the wartime head of US Strategic Air Forces and eventually the first Chief of Staff of the new US Air Force, supposedly refused to read it at all.

|

What remains of the German town of Wesel after an intense bombing raid by the Allies. |

“It” was the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, a detailed and controversial look back at the huge 1940s air wars that the Allies waged against Germany and Japan.

Few documents can boast its staying power. For more than 60 years, the USSBS has colored—some would say distorted—opinion about the efficacy of airpower and the value of the Air Force to the nation. Most major works about airpower reference the survey and its findings in one way or another.

Not bad for a project run by an eclectic group of Wall Street financiers and professors recruited for their total lack of knowledge about airpower.

The authors of the 1992 Gulf War Airpower Survey took “as their standard” the words of USSBS Chairman Franklin D’Olier: “We wanted to burn into everybody’s souls the fact that the survey’s responsibility … was to ascertain facts and to seek truth, eliminating completely any preconceived theories or dogmas.”

The USSBS wasn’t the first such survey. In 1919, the Army Air Service dispatched teams to more than 140 towns bombed by US, British, and French aircraft. That was a miniscule effort compared to the World War II bombing survey, though.

USSBS was a survey to end all surveys. Commissioned with a letter from President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself, it consumed the efforts of 300 civilians, 350 officers, and 500 enlisted men. At more than 200 volumes, the European Theater work alone created a unique record of everything from damage to German synthetic oil refineries to analysis of bombing effects on German railways. A second phase concentrated on Japan and the Pacific war. All told, the survey compiled more than 300 individual reports.

The staff comprised young economists—John Kenneth Galbraith, for instance—who later took up dominant positions in academia and government. D’Olier was the head of Prudential Insurance. Vice Chairman Henry C. Alexander ran J.P. Morgan, the blue-ribbon investment banking house. Survey director Paul H. Nitze, a Wall Street financier, went on to prominence in Cold War policy circles and served as Secretary of the Navy and deputy secretary of defense in the Johnson years.

By the middle of World War II, strategic bombing was taking the war directly to Germany long before ground forces engaged. The survey began in no small part as a way to look at the major targeting controversies (rail vs. oil, and so forth) that had so often consumed the attention of top Allied planners and leaders. Its original intent was to sweep up lessons from Europe for use in the ongoing war with Japan.

Staff members first set up shop in London in November 1944. Most came from anywhere but the air forces. D’Olier, then 68, had been an aide to Gen. John J. Pershing in World War I; he gave his team of 11 free rein. Nitze was a Roosevelt Administration insider brought to Washington at age 33 by James V. Forrestal, who at first kept him on the payroll of the Wall Street firm where both men were partners.

One day, Nitze met with Col. Guido Rinaldo Perera, the organizer of the survey. Perera told Nitze he was “looking for people who don’t know anything about airpower or air attack or anything else, who have had nothing to do with it. Would you be interested?” Nitze was indeed interested and came aboard.

In a way, the economists who staffed the survey were latecomers. Many academics were already mobilized throughout the government in World War II. The Office of Strategic Services, forerunner of the CIA, was one big employer. World War II was “an economist’s war,” remarked OSS employee Paul A. Samuelson, later author of the standard textbook on macroeconomics.

Airpower was often a focus. Economists had since 1942 been at work on methods for prioritizing industrial targets. A young Milton Friedman worked for a time on optimum sizing of anti-aircraft shell pellets. Friedman said decades later that the economists and social scientists were useful chiefly because they were better at working with poor data—unlike physical scientists, who wanted controlled laboratory conditions.

Risks and Costs

Certainly the economists were innovative. According to University of Chicago economist Mark A. Gugliemo, they “realized that to have an impact on the enemy war effort, a bombing raid had to take into account both the depth and the cushion of the enemy industry.” Depth referred to how long it would take the enemy to feel a shortage of tanks or fighters. Cushion measured the enemy military’s capacity to absorb losses from any one industrial sector.

|

Eighth Air Force B-17s release a cascade of bombs over Berlin. |

Nitze and others spent enough time with the air forces in Europe to be impressed with the risks and costs involved. Maj. Gen. Orvil Anderson served as a primary point of contact. In England, Nitze and the survey team also became aware of the heated debates between British and American targeting boards—and Nitze became fast friends with Solly Zuckerman, eminence grise of the British targeteers.

By 1945, survey staff had an unprecedented opportunity to gather empirical data—if they could get there fast enough. Nitze combed the Army manpower records for German speakers and Ph.D. holders and dispatched them to locations such as Schweinfurt to find out about depth and cushion.

Survey staff prided themselves on following the ground troops into key target areas. Their MO was to find factories, round up top production officials, take photographs, and then comb through plant accounts and records. They were so close to the action that four survey members were killed.

“We had to get unambiguous data in such fine detail that it couldn’t be questioned because otherwise people wouldn’t have believed it,” Nitze said.

Interrogations also formed an important part of the survey’s research. Although they talked to Hermann Goering and others, their greatest coup was the interrogation of Albert Speer, the Third Reich’s minister of armaments and industry.

They found Speer holed up in Glucksburg Castle. Nitze, Galbraith, George Ball, and others flew to the site where American, British, and Russian teams were already in place. For 10 days, they grilled Speer in English and German.

Speer “leaned over backwards” to help, claimed Nitze. He “directed us to where we could find the pertinent records of what he had done during the period, including his personal reports to Hitler.” Many of these were in a safe in Munich. Ultimately, Speer “gave us the keys to the safe and combination, and we sent somebody down to get these records,” said Nitze.

The survey turned up real surprises. Germany’s war machine had more depth and cushion than anyone realized. Galbraith calculated that Hitler did not truly mobilize the German economy until late in the war. Partial German demobilization after the fall of France in 1940 left the economy with excess capacity.

The Germans did not fully mobilize again until late 1944—a date that coincided with the tremendous increase in the weight of strategic bombing attacks. Conclusions about the capacity of the German economy rippled throughout the economics-based analysts of the bombing campaign. It led the survey’s analysts to rate many famous attacks—including the bloody efforts at Schweinfurt and Regensburg—as less effective than attacks on oil targets.

“When it came to the attacks on the synthetic oil plants and the related chemical plants, those attacks were much more successful than the planners had anticipated,” Nitze recalled.

|

B-29s from the 20th Bomber Command release tons of bombs on a large Japanese supply depot in Burma. |

Air attacks worked best on industries where repairs were difficult and alternatives were few. The European summary report pointed out that even the most heavily attacked industries had a way of reconstituting. In the case of ball bearings, there were extreme work-arounds and, of course, Swedish imports.

Airpower Was Decisive

As for morale, the survey found Germany’s civilian economy had substantial cushion in consumer goods, a factor that helped keep up morale.

For all that, the European report was unequivocal in its assessment of the contribution of airpower.

Here is what it stated: “Allied airpower was decisive in the war in Western Europe. Hindsight inevitably suggests that it might have been employed differently or better in some respects. Nevertheless, it was decisive. In the air, its victory was complete. At sea, its contribution, combined with naval power, brought an end to the enemy’s greatest naval threat—the U-boat; on land, it helped turn the tide overwhelmingly in favor of Allied ground forces. … It brought the economy which sustained the enemy’s armed forces to virtual collapse.”

Had the survey ended its work after V-E Day, it might have remained just a fitting conclusion to the targeteering debates that surrounded strategic bombing during the war. Instead, Gen. Henry H. Arnold, the US Army Air Forces Chief, set the staff loose on the Pacific campaign while it was still going on.

Nitze came up with plans to halt fire-bombing in favor of concentrating on targets such as railway tunnels. Branching from this work, Nitze and colleague Fred Searls Jr., a geologist, conjured a targeting plan to force Japanese surrender through interdiction of the rail system and other lines of communications targets. Nitze estimated that, by bombing the right targets, Japan would be unable to hold out past March 1946.

All of that planning became moot when B-29s dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, ending the war.

President Harry Truman sought a full survey of the air war in the Pacific. Nitze once again took a leading role. This time, the survey was plagued with problems. It had to include the naval campaigns—a tasking that became the opening round of postwar roles and missions battles.

Once again, survey experts tracked down industrial and municipal records and gleaned details about the direct effects of the atomic attacks. They found that train passengers who’d been sitting near open windows suffered more radiation effects. Passengers with closed windows suffered cuts and wounds from shattering glass but gained some protection from radiation. It made for compelling reading.

The main findings of the Pacific war report were ready in June 1946. Like the European report, it praised airpower far and wide, but it made a dramatic, bombshell claim:

“Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts,” it read, “and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the survey’s opinion that certainly prior to 31 Dec. 1945 and in all probability prior to 1 Nov. 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.”

The summary report made the case that it was just a matter of time until Japan realized its “military impotence” and accepted the inevitable. In their opinion, air supremacy over Japan could have exerted enough pressure to bring about unconditional surrender.

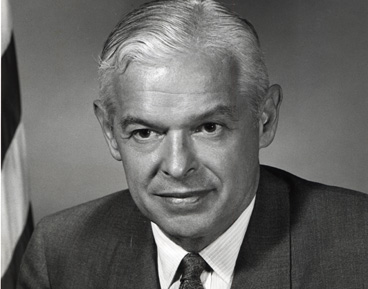

|

Paul Nitze, who directed the USSBS, held high national security posts in later Administrations. |

This startling conclusion was directly traceable to the truncated targeting work performed by Nitze in early summer 1945. At that time, Nitze had pushed hard for the new targeting plan based on his experience in Europe and a quick survey of Japanese targets. He’d gone so far as to take the proposal to James F. Byrnes, who would become President Truman’s Secretary of State.

Nitze’s friend Forrestal, now Secretary of the Navy, had poured cold water on the idea. He pointed out that millions of men converging on the Pacific Theater couldn’t be kept waiting for months in hopes Japan would surrender.

A bigger roadblock was the opposition of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Chiefs didn’t see much military merit in wait-and-see operations, and they blocked it.

It was a bureaucratic slight Nitze did not forget. Unlike with the European work, where the USSBS staff conducted deep and searching interrogations, the abrupt end to the Pacific war caught the survey team with an open-ended theory and no data to prove it. Even so, Nitze and the report authors ended up putting the theory into the Pacific war summary.

The survey’s widely published conclusions became source material for questions about whether the Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks were a military necessity. While a group of scientists had written to Truman imploring him not to use the bomb, their objections rested on wider moral grounds. Nitze’s assertions were the first to attempt an authoritative military case for another alternative.

The Only Possible Decision

When Nitze injected his theory into the Pacific war report, it sparked a controversy that has lasted for generations. Thirty years later, Nitze sat for an important oral history in which he allowed, “It seems to me that Mr. Truman made the only possible decision.” By then, though, Nitze was too late. The Pacific war survey, with its hedging about atomic attacks, had already given critics the leverage they needed.

The speculations of the Pacific war volume and the cool statistical conclusions of the European war summary accounted for much of its staying power.

Yet part of the reason for the longevity of the USSBS was that the Army Air Forces commanders did not produce a comparable operational survey of their own.

In Britain, Air Chief Marshal Arthur T. Harris penned a final report titled, simply, Despatch on War Operations. This commander’s history covered the period from February 1942 to May 8, 1945. It had a blend of tactical and operational detail not found in the US survey. It was too technical, in fact, for the RAF to declassify it after the war and the study languished for decades in the Public Record Office until finally printed in 1995.

The snappy statisticians of the USSBS cut to the chase with more statistics than adjectives. The terse and direct verbiage of the survey’s two summaries served it well. Most of all, the analysis of industrial effects remained a guide to what might happen in a nuclear war.

|

B-17 Flying Fortresses of the 398th Bomb Group approach Neumunster, Germany, in 1945. |

The survey, then, endures as the main source document for views on strategic bombing. The survey’s great strength was also its great deficit. By concentrating on effects, it left no room for the operational context of major campaigns and command decisions.

In the end, the survey left its deepest marks on the academic debates about strategic bombing and airpower in general. What Nitze, Galbraith, and others on the survey staff could not have predicted was that their careful and precise work would remain open to so many varying interpretations.

Writer Rick Atkinson, in his 1993 book Crusade, quoted verbatim a Pacific war survey sentence that he held out as evidence of how “historical baggage pressed” on Air Force planners commanding air strikes in the 1991 Gulf War. In 1994, controversy over the Smithsonian’s plan to exhibit the Enola Gay bomber linked directly back to the doubts raised by the Pacific war summary volume of the survey.

A few years later, historian Thomas A. Hughes concluded his scholarly study of airpower and Operation Overlord with zingers on the failure of bombing. Hughes also complained that the USSBS “appropriated” accomplishments of tactical air by mushing together fighter and bomber results of attacks on transportation systems, for example.

For other authors, the survey stood out as gold-standard proof of the evils of strategic bombing. A recent example of this was Stephen Budiansky’s 2004 book Air Power, which threw USSBS data together with others—some British—to make his case.

The survey itself was plain enough. It delivered its precise analysis of input, output, cushion, and depth. But its verdict on airpower was uncompromising. It was, in a word, decisive. That, too, has stood the test of time.

Rebecca Grant is a contributing editor of Air Force Magazine. She is president of IRIS Independent Research in Washington, D.C., and has worked for RAND, the Secretary of the Air Force, and the Chief of Staff of the Air Force. Grant is a fellow of the Eaker Institute, the public policy and research arm of the Air Force Association. Her most recent article, “The Dogs of Web War,” appeared in the January issue.