Among the 14 general officers who were dismissed or have announced early retirement since President Donald Trump took office in January, two appear likely to have long-term institutional impact for the Air Force: the departures of Vice Chief of Staff Gen. James Slife in February and the impending retirement of Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin this fall.

By effectively beheading the Air Force’s military leadership, the new administration cast into doubt initiatives launched in the past two years intended to reshape the design, operations, and organization of the service.

Allvin and Slife were the military leaders on the small team assembled by Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall to lead a proposed revamp dubbed “Re-optimization for Great Power Competition,” a collection of about two dozen changes intended to reset the Air Force to better deter or defeat China in the future. Some of those changes, such as department-level exercises and the revival of warrant officers, could prove enduring.

But others, such as centralizing the requirements process within a new Integrated Capabilities Command, or reorganizing Air Force wings to present standardized force packages to combatant commanders, may not survive without the leaders who championed them. ICC and other re-optimization programs have been effectively on hold since early February, following an order from Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth.

Those ideas, along with Allvin’s push to de-emphasize the Air Force’s major commands, were unpopular among his fellow four-stars, particularly with the two leading contenders to replace him: Air Force Global Strike Command boss Gen. Thomas A. Bussiere, already nominated to succeed Slife as vice chief, and Gen. Kenneth S. Wilsbach, who recently departed as the head of Air Combat Command, but has not yet officially retired.

“The four stars who run [Air] Mobility Command, Global Strike, and Air Combat Command, in particular, kind of view themselves as somewhat quasi-independent,” one former civilian official told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “They want to have a lot of authority over what happens in those stovepipes.”

Global Strike Command oversees the Air Force’s bomber and missile forces, two legs of the nuclear triad, and is responsible for both developing and manning the weapons and platforms. Air Combat Command has parallel responsibilities for the fighter force. That vertical integration is a strength, but Kendall also saw it as fueling disconnects between different parts of the force, particularly in systems’ ability to communicate and share data in real time.

Kendall wagered the success achieved in his first two years on the job on a final drive to engineer and implement a more integrated approach to weapons development and other re-optimization changes. He dedicated his entire last year to seeing that through and believed the moves would endure after he departed.

“They’re all about the heart of the matter of how we organize, train, and equip the force,” he told reporters at AFA’s 2024 Air, Space, and Cyber Conference. “The support goes down through the ranks. … I’m really not worried.”

If there was support through the ranks, however, there was not support from the new administration. It took Hegseth barely two weeks to freeze those initiatives pending the arrival of a new secretary and undersecretary of the Air Force. Now, with a new chief of staff coming on board, it is safe to expect that individual will also get a say on the future of those plans.

Air & Space Forces Magazine spoke with six current and former Air Force officials who were granted anonymity in order to speak candidly about sensitive matters. They said Allvin grew unpopular as he forged ahead in the face of opposition from his fellow generals, who saw the ICC and deployable combat wing initiatives as misguided and impractical. These critics say Allvin ignored operational input, sought to stretch the force too thin, and didn’t do enough to prepare the service to face off with China.

“This is not the point in your career where you get to figure things out along the way,” one retired general officer said. “This is the point in the career where you were hired for your wisdom, your intellect, and your ability to get things done.”

Their complaints eventually reached civilian leadership, who gave Allvin the chance to retire rather than be openly fired, sources said. How Trump, Hegseth, or Air Force Secretary Troy E. Meink arrived at the decision remains unclear. The White House did not respond to a request for comment on Allvin’s planned retirement. A Pentagon spokesperson referred questions to the Air Force, where another spokesperson declined to comment.

But conditions in the Trump administration were ripe for Allvin’s unusual exit, sources agreed. Some suggested he could have bowed out on his own if his vision for the future didn’t match that of the Trump administration, or if he saw a dead end looming after Trump nominated Bussiere—an officer sources said had clashed with Allvin—to be vice chief. Yet it seemed clear from Allvin’s public comments and statements that he was working to align his initiatives to the administration’s approach.

“We have seen a preference by this administration to want to put into key roles military leaders that they deem are fully aligned with what the administration is trying to accomplish,” a second former civilian official said. “It seems that Gen. Allvin has endeavored to align his approach in the Air Force to this administration’s priorities, but perhaps the administration view is different.”

Indeed, the tone of Allvin’s social media and other communication changed with the arrival of a new administration. He tweeted about “warheads on foreheads” and at AFA’s Air Warfare Symposium in March, he inserted a clip from Hegseth’s confirmation hearing to demonstrate alignment with the new secretary’s priorities. Later, after getting the go-ahead to declare a winner in the Next-Generation Air Dominance fighter competition, he designated the future jet the F-47, a reference to Trump as the 47th president of the United States.

Multiple former Air Force officials warned that dropping the programs pursued by Allvin, Slife, and Allvin’s predecessor as chief, Gen. C.Q. Brown Jr.—who Hegseth fired as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in February—could undermine the service in the future. The former officials expressed concern about adequate budgeting and the ability to sustain operations like the June airstrikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, for example. The turnover could spur a new look at how much money the Air Force requests from Congress and how it’s spent.

The short-term outlook may not change much; if China tries to invade Taiwan in 2027, as Chinese President Xi Jinping has told his generals to prepare for and as some U.S. officials believe is possible, deployable combat wings that could help defend the island nation would still be in their relative infancy. But risk to the U.S. grows the longer the Air Force puts off a major revamp, the first former civilian official said.

Removing senior military officers who have been instrumental in defining the future force “really undermines the bipartisan approach to China,” the second former civilian official added.

The clock is ticking to name Allvin’s replacement, and a nomination could come as soon as this week.

Wilsbach is a decorated fighter pilot experienced in the Pacific, including nearly four years commanding Pacific Air Forces prior to taking over ACC in February 2024. Wilsbach’s wife Cynthia has worked in both Trump administrations, where she is now a senior writer for presidential correspondence, White House records show.

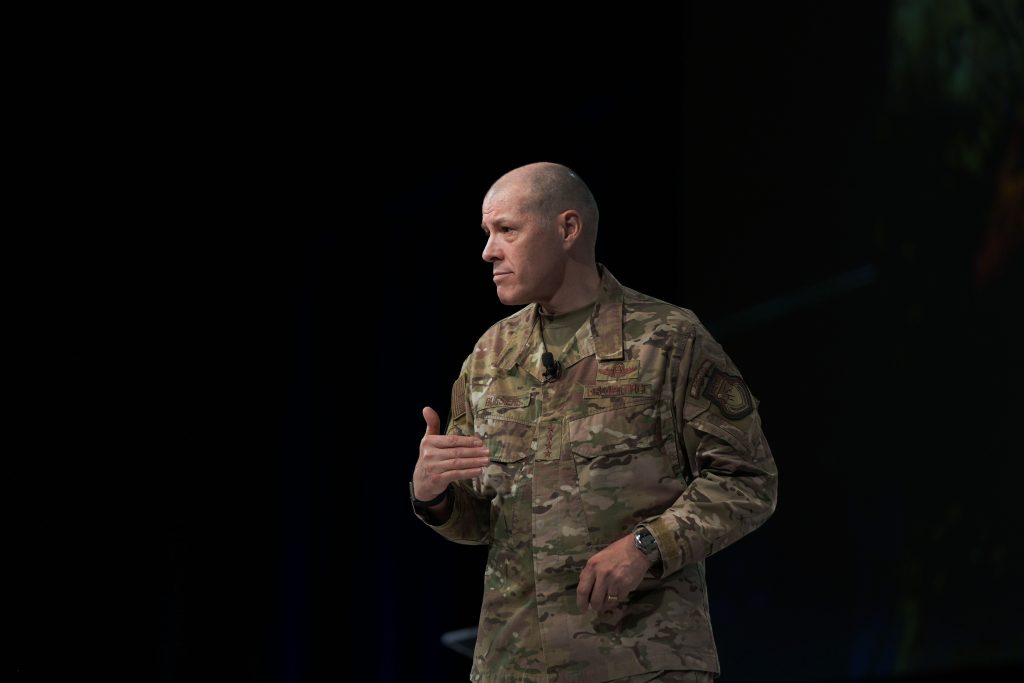

Bussiere, who as head of Air Force Global Strike Command was the top officer in charge of the bomber fleet when Operation Midnight Hammer struck Iran in June, is another possible contender for chief.

“Bussiere is a force of nature,” the retired general officer said. “He is incredibly passionate. He has incredibly high standards. He’s gruff, he’s direct, he’s got an enormous foundation of operational credibility. He’s savvy, and he doesn’t sit on an opinion just because it’s counter to what the head of the table thinks.”

Neither four-star is a fan of Integrated Capabilities Command or the design of deployable combat wings, sources said, making it more likely that those initiatives would be scrapped if either becomes chief of staff. As secretary, Meink would ultimately have the final say in whether they move forward than the chief of staff.

In all, seven Air Force generals have been dismissed from top roles in the U.S. military since January—comprising half of the total general and flag officers ousted so far, and more than any other branch of the armed forces.

In addition to Brown, Allvin, and Slife, the list of Airmen dismissed by the Trump administration (from most recent to earliest) include:

- Defense Intelligence Agency Director Lt. Gen. Jeffrey Kruse: Fired Aug. 22, possibly because a leaked preliminary assessment of limited damage to Iranian nuclear sites clashed with Trump’s view, according to the Associated Press

- U.S. Cyber Command and National Security Agency boss Gen. Timothy Haugh: Fired in the spring. Right-wing activist Laura Loomer appeared to take credit for his ouster with a social media post suggesting Haugh had ties to the Biden administration and Army Gen. Mark Milley, Brown’s predecessor as chairman of the Joint Chiefs.

- Lt. Gen. Jennifer Short, the senior military assistant to the defense secretary: Fired in March when Hegseth sought a new military aide

- Judge Advocate General of the Air Force Lt. Gen. Charles Plummer: Fired by Hegseth in February, along with his counterpart in the Army, in a bid to install lawyers aligned with the Trump administration’s objectives

Air Force Gen. Dan Caine replaced Brown as the military’s top officer. Bussiere is nominated to replace Slife, and Short retired. Haugh’s deputy, Army Lt. Gen. William J. Hartman, is now acting head of CYBERCOM; Plummer’s replacement has not yet been named.

Though it’s too soon to tell how removing Airmen from key joint positions could shape the service’s influence on military operations, the second former civilian official argues Congress should probe the potential impact that axing more than two dozen Senate-confirmed officers might have on the services.

Others argue the Air Force remains stable and the Airman’s perspective in the joint force prevails.

“The reality is, military organizations are used to people coming and going at unexpected times and in unexpected ways,” the retired general officer said.

Allvin’s early departure makes his tenure among the four shortest among the 23 chiefs of staff since 1947 when the service was founded. The only shorter tenures were those of the first chief, Gen. Carl A. Spaatz, who had run the Army Air Forces prior to the Air Force’s independence and who held the job for only about nine months; Gen. George Brown, who was promoted to become chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff after less than a year as CSAF; and Gen. Mike Dugan, who was fired after less than three months on the job in September 1990 for telling reporters how he expected the Iraq war might be waged.

Allvin will become the fourth CSAF to depart early in the past 35 years—totaling about one-third of the 11 chiefs in office since 1990. In addition to Dugan, Gen. Ronald Fogleman resigned over a dispute with Secretary of Defense William Cohen in 1997, and Gen. T. Michael Moseley was fired in 2008 by Defense Secretary Robert Gates over the Air Force’s mishandling of nuclear weapons and his insistence that the Air Force invest in high-end capabilities to fight peer threats in the midst of low-end counterinsurgency conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In contrast, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Lisa Franchetti and Coast Guard Commandant Adm. Linda Fagan were the only other chiefs fired or who retired early from the top of any U.S. military service during that same period. The Trump administration ousted both women within weeks of taking office.

Rachel S. Cohen contributed to this story.