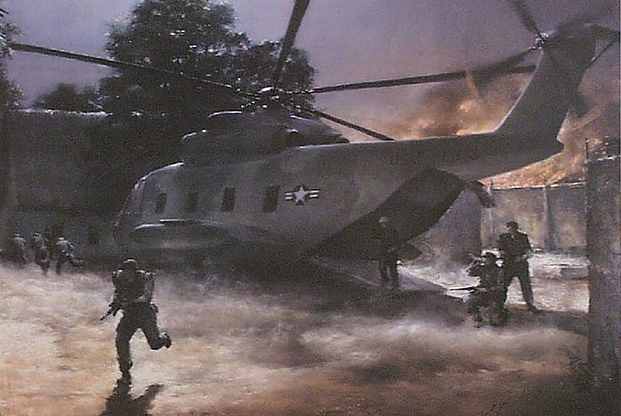

Raiders exit a deliberately crashed helicopter at the Son Tay prison camp in North Vietnam. Painting: Mikhail Nikiporenko/USAF

Poring over reconnaissance photos in May 1970, US Air Force intelligence analysts noticed a new wall and a new guard tower at an enclosed compound near Son Tay on the Song Con River, 30 miles west of Hanoi.

Closer inspection revealed rocks in a corner of the compound, arranged in the shape of the letter K—search and rescue code for “come and get us.”

Intelligence first estimated there to be six, then 50, then 70 American prisoners of war at Son Tay.

In 1970, the US knew the names of more than 500 POWs held in North Vietnam. Several of the prisons—including Hoa Lo, the infamous “Hanoi Hilton”—were located in the North Vietnamese capital itself, where the POWs were beyond any hope of rescue.

That was not the case with Son Tay and consideration of a rescue began right away. For various operational and political reasons, though, it would be six months before everything was ready to go.

The concept for the raid was approved by the Joint Chiefs of Staff on July 10.

It was the first joint military operation ever conducted under direct JCS control. Extraordinary secrecy was imposed. Even US Pacific Command and Military Assistance Command Vietnam, in whose territory it would occur, were not in the loop. Execution of the plan required approval by the president.

The mission was launched just before midnight Nov. 20 and involved 116 aircraft flying from seven air bases and three aircraft carriers. The ground assault was conducted by 56 US Army Special Forces troops. Only the planners and leaders knew the destination ahead of time. The rest of the raiders were kept in the dark until the mission was underway.

The attack force descended with complete surprise on Son Tay in the early morning hours of Nov. 21. From a military standpoint, the operation was almost perfect. Even the single mistake turned out to be fortunate.

However, the first report flashed back from Son Tay was staggering. The POWs were not there. As it was later determined, they had been moved while the rescue was still in the planning stages.

EGLIN

May 1970 was not a good time to suggest a raid deep into North Vietnam. The controversial incursion into Cambodia at the beginning of the month was fresh in the news. Public clamor was for winding down the war as rapidly as possible.

The United States no longer had agents in North Vietnam to aid in the insertion. Nine such teams, 45 trained Vietnamese, were abandoned after the bombing halt in 1968.

The proposal for a raid was sponsored mainly by the joint counterinsurgency/special activities staff. Their feasibility study in June led the Joint Chiefs to approve the operation in principle in July. The planning and training phase, which began in August, was designated “Ivory Coast,” and was disclosed to as few people as possible.

Air Force Brig. Gen. LeRoy J. Manor was chosen as mission commander and Army Col. Arthur D. “Bull” Simons was named as deputy and ground force commander. Most of the training was in a secluded section of the Florida panhandle at Eglin Air Force Base Auxiliary Field No. 3, near where the Doolittle Raiders trained for their mission against Tokyo 28 years previously.

Air Force aircrews and Army Special Forces troops prepared for a mission that would involve dissimilar aircraft flying close together at low level at night, under radio silence, and landing an HH-3 Jolly Green helicopter inside the walls of the compound.

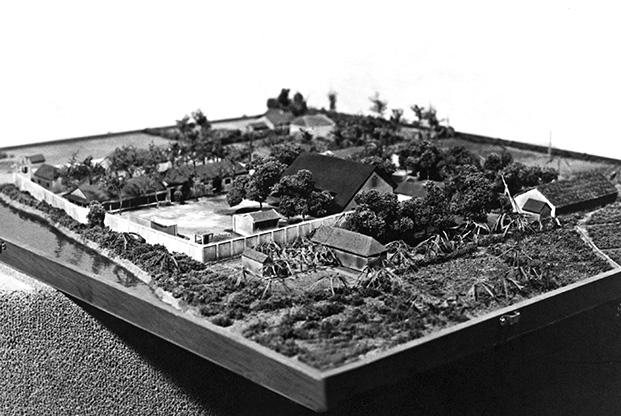

The CIA built a tabletop replica—code named “Barbara”—of the Son Tay compound. Optical viewing equipment permitted the camp to be studied as it would appear under various lighting conditions and phases of the moon, and from any angle.

There was a full-scale mockup of the camp. The dimensions of the buildings were carefully staked out by two-by-four posts in the ground with yards of cloth stretched between them to simulate the walls.

An abiding myth, still repeated today, is that the mockup was dismantled every morning lest it be discovered by a Soviet Cosmos satellite that passed over Eglin twice a day. The posts were supposedly removed, the cloth rolled up, and the post holes covered with lids. Daylight training was limited to times when the satellite was not in position to observe.

In fact, USAF reconnaissance photos showed that such labor-intensive disassembly was not necessary. “The cloth walls were not distinctive enough to suggest solid structures,” said Maj. John Gargus, lead navigator for the strike force. “The site looked like a stockyard in repair,” and it was “highly unlikely that even the sharpest photo interpreter would identify the construction as the Son Tay camp.”

Manor traveled from command to command to line up resources, everything from helicopters and fighters to aeromedical transports. He had to deal with senior officers who could not be told about the mission. He was aided in this by a letter from USAF Chief of Staff Gen. John D. Ryan directing commanders to give Manor whatever he needed, no questions asked.

The CIA built a tabletop replica of the Son Tay camp so it could be studied from all angles. Photo: National Archives

ASSEMBLY

The direct strike would be conducted by 28 aircraft: six helicopters, two MC-130 pathfinders, and 20 fighter-attack escorts.

Five of the helicopters were HH-53C Super Jolly Green Giants. They would fight their way into Son Tay, deliver the Army assault force, and bring the POWs out. The other helicopter, a smaller HH-3E Jolly Green, would land inside the compound.

Neither the helicopters or the five A-1 Skyraiders, going along to prove close air support, had the navigational capability to fly the precise approach to the camp in the dark, so they would be led there by the MC-130s.

The Air Force had only 12 of the highly classified MC-130E Combat Talon special operations aircraft. They were coated with early stealth reflective paint, and because of their terrain-following radar and other electronic features, they were always parked in their own part of the ramp with armed guards to prevent unauthorized persons from getting too close.

The formations would be difficult to maintain since the helicopters, the Skyraiders, and the MC-130s flew at significantly different speeds.

Manor forecast two “windows” for the mission—Oct. 21 to 25 and Nov. 21 to 25—times when moonlight conditions would be ideal. National security adviser Henry Kissinger ruled out the October option as in conflict with “ongoing political discussions” with China. Thus the November window was chosen for Operation Kingpin, as it was designated.

Intelligence reports were mixed. High-altitude imagery from the SR-71 was supplemented by low-level photos by the Ryan 147S Buffalo Hunter drone.

None of it was conclusive. A source inside North Vietnam said the POWs were no longer at Son Tay, but SR-71 overflights Nov. 2 and Nov. 6 revealed “a definite influence in activity.”

Tight security complicated matters. In early November, the CIA station chief in Saigon insisted on using the HH-53C helicopters for a raid in Laos and was unwilling to take no for an for answer without being told why. USAF broke the impasse with an elaborate subterfuge in which all of the HH-53s were temporarily grounded, allegedly for safety reasons. An exception was made for Son Tay, but not for the CIA.

The joint force began deployments from Eglin Nov. 10, and by Nov. 14 was in a secure area of Takhli Air Base in Thailand. President Richard M. Nixon’s formal approval for the mission arrived Nov. 18.

The strike was supposed to begin on the night of Nov. 21 but that was upset by a typhoon, moving slowly toward the mainland from the Philippines and forecast to bring bad weather to North Vietnam. Manor advanced the timing by 24 hours. The mission would go on Nov. 20.

Manor’s command post would be at Monkey Mountain, a USAF tactical air control center near Da Nang in South Vietnam, where he had communications with all elements of the force, including aircraft carriers and the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Simons would go to Son Tay as on-site commander. At Takhli, he selected the 56-member ground force from the 100 troopers who had deployed—an expected action but nonetheless disappointing to the 44 not chosen.

On the evening of Nov. 20, Simons told the assault team that the mission was to rescue POWs at a place called Son Tay. They boarded transports for a short hop to Udorn Air Base in northern Thailand, where the helicopters were waiting.

Special Operations troops assigned to the Son Tay raid. Fifty-six troopers were selected for the ground raid. Photo: USAF

INGRESS

First up were the Combat Talon MC-130Es, which took off from Takhli and were joined over Laos by the helicopters from Udorn and the A-1 Skyraiders from Nakhon Phanom. They refueled from HC-130P tankers and took up a low-level course across the mountains for Son Tay.

Shortly after midnight on Nov. 21, three US Navy carriers from Task Force 77 in the Tonkin Gulf began a massive diversion, launching 59 sorties that dropped flares in the vicinity of Haiphong harbor. This completely captured the attention of the North Vietnamese air defense system which did not notice the small raiding party approaching from the other direction.

Over Laos, the air assault force divided into two elements, the six helicopters behind one of the Combat Talon C-130s and the five Skyraiders behind the other.

“The normal cruise speed of a C-130 at low level is about 250 knots,” said Benjamin Schemmer in The Raid, published in 1976, the first detailed account of the operation. On this night, however, the MC-130s were held back to 105 knots, 10 knots above stalling speed.

“They had to fly that slow because the helicopters couldn’t fly any faster,” Schemmer noted.

The helicopters were stacked in echelon, three on each side, slightly above and behind the wings of the Combat Talons. “They would have to fly ‘in draft,’ tucked in close enough behind the C-130’s wings to be ‘sucked along’ in the plane’s vacuum,” Schemmer said. The other formation, with the A-1s trailing the second MC-130, flew in close proximity.

Also en route to Son Tay were 10 F-4D Phantom fighters from Udorn to provide protection against MiG interceptors and five F-105G Wild Weasels from Korat for SAM suppression. The Red River basin, where the assault force was heading, was a hotbed of SA-2 surface-to-air missiles and anti-aircraft artillery.

All arrived undetected over Son Tay, and at 2:18 a.m. the lead Combat Talon dropped four flares to light up the night sky and the camp. One of the Super Jollys swept low over the prison to demolish the guard towers and strafe the barracks with its Gatling machine guns.

29 MINUTES

At precisely 2:19 a.m., the HH-3 Jolly Green helicopter set down hard in a small space inside the prison walls, the rotor blades chopping limbs from the trees as it went in. One large tree was completely severed and limbs and debris were still falling as the troops dismounted.

Damage to the HH-3 did not matter. Its trip was planned as one-way all along, and the demolition charges were already in place, set to explode on a timer.

The first raider off the HH-3 announced with a broadcasting bullhorn that, “We are Americans! This is a rescue!” The assault team soon disposed of the guards as they emerged and a room-by-room search began.

Two of the HH-53s broke away to wait nearby in a holding area until called to pick up the rescued POWs. The other two Super Jollys were supposed to land adjacent to the prison compound to deliver the ground force.

One of them did so, but the other—specifically the one carrying ground force commander Simons and 22 raiders—mistakenly landed 400 meters south alongside a similar-looking compound labeled “Secondary School” on the intelligence maps.

The mistake turned out to be extremely fortunate. The Secondary School was occupied by a contingent of more than 100 enemy troops, and a firefight ensued. Had Simons and his party not stumbled across them, they would probably have struck the US troopers at the main compound by surprise and with considerable effect.

The Secondary School defenders did not wear North Vietnamese Army dress and were taller than usual for North Vietnamese. The Americans figured them to be Chinese or Russians. One of the raiders whose belt broke during the attack stripped a replacement from one of the fallen defenders. The buckle was later determined to be that of a Chinese officer.

The A-1s attacked and destroyed a small bridge on the Song Con River when activity was detected on the other side. The fighters maintained orbit over the camp but encountered no challenge.

“The raiding element was on the ground for not more than five minutes when the mistake was realized,” Manor said. “Simons and his men reboarded the helicopter and moved into the correct position at the Son Tay prison. The entire camp was searched and the devastatingly disappointing discovery was made that there were no Americans at the camp. The coded message—”Negative Items”—was received at my command post.” The code word for POW was “item.”

The raiding party began pulling out of Son Tay at 2:40 a.m. They had been on the ground for 29 minutes, a minute less than anticipated in the plan.

REACTION

The SAMs, silent until now, opened up as the raiders departed. They were immediately engaged by the F-105 Wild Weasels, one of which was damaged by a rising SA-2 missile. The F-105, leaking fuel, went down before it could reach the tankers over Laos. The crew landed uninjured in the mountains and was subsequently rescued. Otherwise, the total US casualties amounted to a broken ankle and one minor bullet wound.

The assault force was out of North Vietnam by 3:15 a.m. and back to Udorn at 4:28 a.m., roughly five hours after takeoff. “I received a message from Admiral Moorer [the JCS chairman, Adm. Thomas H. Moorer] instructing me and Simons to return to Washington posthaste,” Manor said.

Flanked by Manor and Simons at a press conference in the Pentagon on Nov. 23, Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird announced the basic facts of the mission. “The rescue team discovered that the camp had recently been vacated,” Laird said. Manor and Simons declined to answer questions about details.

The headline in the Washington Post the next day was “US Raid to Rescue POWs Fails.” Reaction from Congress was mostly supportive, but Sen. J. William Fulbright (D-Ark.)—chairman of the Armed Services Committee and a foremost critic of the war—called the raid “a very provocative act” that represented “a very major escalation of the war, that it seems to me, will entail greatly increased conflict between North and South.”

Sen. Birch Bayh (D-Ind.) said it was a “John Wayne approach” that might lead to “POWs being executed.”

The predictions of dire consequences proved unfounded. “The North Vietnamese, fearing a repeat performance but not knowing when and where, closed down the outlying POW camps and consolidated all POWs into the two remaining prisons in downtown Hanoi,” Manor said. “The number of POWs in these prisons now grew to the extent that POWs lived in groups rather than what for many had been solitary confinement. Morale immediately improved, and as a result, general health improved.”

A total of 96 decorations were presented to Air Force and Army participants. Every member of the ground assault force received the Silver Star or a higher decoration. Originally, Army bureaucrats had decided that the Army Commendation Medal—a minor award—was sufficient for more than half of the raiders. They backed down when Simons told the Chief of Staff that his team, regarding such “recognition” as insulting, might refuse to accept the Commendation Medal.

PERSPECTIVE

It has been established that the POWs were removed from Son Tay in July.

There is conjecture, still repeated today, that this was done because of flooding of the Son Tay River—supposedly related to a CIA cloud-seeding program to generate heavy rain to wash out road surfaces and river crossings.

This theory has been largely debunked.

“We moved—pure, plain, predetermined administrative move to quarters that had been in the planning and building for us for a considerable period of time,” said Air Force Col. Richard A. Dutton, who was a prisoner at Son Tay.

“It was just coincidence.”

The mission is regarded as a major event in special operations history. The Son Tay Raider Association was formed in 1990 and for many years held reunions and conducted informational programs.

In a thoughtful essay for Parameters, the journal of the US Army War College, USAF Lt. Col. Mark Amidon said the planning and training for the mission “stands arguably as the preeminent model of all special operations missions conducted by the US military.” It is in sharp contrast with Desert One, the disastrous effort to rescue US hostages in Iran in 1980, aborted after the loss of aircraft and lives in the middle of a sandstorm.

Lt. Gen. Donald V. Bennett, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, “appeared before Admiral Moorer on the morning of 20 November with two stacks of ‘evidence,’ one saying ‘they’ve moved’ and an equally large one saying ‘they’re still there’,?” Amidon said.

The unavoidable question is the extent to which decision-makers allowed themselves to be convinced by what they wanted to believe. In his essay, Amidon concludes that it was a case of “collective rationalization” and “group think” at the Pentagon.

John Gargus, the lead navigator for the mission and the author of his own comprehensive account of the operation, agrees with Amidon.

“Military leaders in Washington were so motivated and committed to the rescue of the prisoners that their desire for solidarity and unanimity overrode any realistic appraisal of what was facing them,” Gargus said.

John T. Correll was the editor-in-chief of Air Force Magazine for 18 years and is now a contributor. His most recent article, “The Making of MAD,” appeared in the September 2018 issue.