The Space Force’s first planned satellite launch to begin a new missile warning constellation in medium-Earth orbit has slipped from late 2026 to spring 2027 as a key component remains unproven. But the service is making progress and moving forward with plans for new batches of satellites, the Guardian in charge of the effort said July 1.

Just last month, Space System Command’s space sensing directorate announced it had awarded a contract to BAE Systems for 10 satellites as part of what it’s calling “Epoch 2” for its Resilient Missile Warning/Missile Tracking MEO program. During a webcast with AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, Brig. Gen. (Select) Robert W. Davis said the Space Force plans to issue another contract for more Epoch 2 satellites this fall.

Davis noted that the second contract could cover two more “planes” of satellites. Budget documents indicate that could mean 10 to 12 more satellites.

“We’re seeing a huge response from the industrial base every time there’s a call for proposals and the source selection for a tranche or an epoch,” Davis said. “We’re seeing that response coming from industrial base. That’s very exciting, as we are able to pull in nontraditional players in this area that drives innovation.”

In many ways, the Resilient MW/MT MEO program is following in the footsteps of the Space Development Agency’s own missile tracking architecture in low-Earth orbit, Davis noted. Like SDA, his team is taking an incremental approach, regularly competing and awarding multiple new contracts instead of consolidating them into one big deal. By doing so, they hope to spread out their missile warning capability across many different satellites, incorporate new technologies faster, and encourage more competition.

Yet just as SDA has run into delays executing its breakneck timelines, SSC has also encountered hiccups.

Davis acknowledged supply chain issues and technical challenges have cropped up as the service tries to institute the “right testing, the right rigor on the ground, so once we get to orbit, we have a functional system.”

As a result, Epoch 1’s first launch, originally scheduled for the end of fiscal 2026, has now been pushed back to sometime in the first half of the 2027 calendar year.

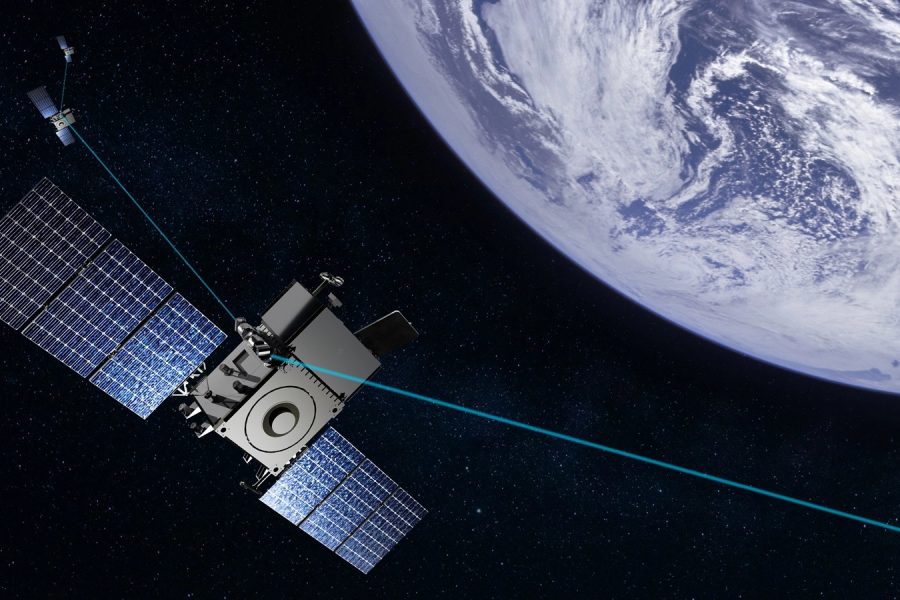

Another similar issue facing both SDA and SSC involves the laser optical crosslinks that will pass data between satellites, a much faster and more secure process than radio frequency signals offer.

SDA has established some laser crosslinks in low-Earth orbit with its demonstration “Tranche 0” satellites, but the technology is still relatively new. The watchdog Government Accountability Office argued earlier this year that the agency was investing too heavily in the option without being certain it will work.

Davis called the laser crosslinks the “linchpin” of the new proliferated constellations in low- and medium-Earth orbit, but also said it is the potential risk to the MEO program the Space Force is watching the closest.

To address that risk, “we’re really leaning into lessons learned at Tranche 0 and investing more in our ground architecture to be able to do more testing and risk mitigation of that crosslink technology,” Davis said. That way, the service will be more prepared to respond to any issues that pop up on orbit.

There are differences between the work underway at SDA and SSC. Unlike SDA, which is trying to establish crosslinks between satellites built by different vendors, Davis’ team at the space sensing directorate “made the choice not to push the envelope on the crosslinks,” he said. As a result, Epochs 1 and 2 will have crosslinks connecting satellites from the same vendor, but not between systems built by different companies.

The optical crosslinks at medium-Earth orbit will also require different standards than those at low-Earth orbit, given the distances and altitudes involved. Davis said his team is working with SDA and industry on those baseline requirements.

“We’re in a little bit of a horse race to see which one’s going to mature in the industrial base, which one’s going to be the best to put on contract for Epoch 3,” he said.

Despite the challenges, Davis argued that new missile warning capabilities in low- and medium-Earth orbits are necessary to complement the Pentagon’s existing legacy systems in geosynchronous orbit that have proven their worth against real-world threats in recent years.

“We have a very robust missile warning architecture today,” Davis said. “It has shown that the nation can defend itself, can help our allies defend themselves. That’s absolutely working today.”

“What we don’t have,” he continued, “is architecture that’s responsive to the emerging threats. And so this first set of tranches and epochs are hyper-focused, pun intended, on those hypersonic targets and other dim targets that are out there that are really more challenging to the current architecture.”

Perhaps the most important part of that architecture, Davis said, is the ground segment that will ingest huge amounts of data from the many new sensors on satellites going into orbit. For the MEO constellation, Davis’ team is working on a system called FORGE that will also be used for missile warning satellites in geosynchronous and polar orbits.

As with the satellites, Davis said his team is taking an incremental approach to the ground system that asks smaller companies to develop “chunks” of software at a time. The ground segment is poised to receive around $350 million in 2026.