Everything’s coming together to make 2025 a pivotal year in the Space Force’s long-running effort to make GPS more resistant to jamming, a senior service official said April 29.

“That entire architecture is really focused now on meeting the anti-jam and spoofing threat,” said Cordell A. DeLaPena, program executive officer for military communications and position, navigation, and timing, said during a virtual Schriever Spacepower talk with AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

GPS remains the gold standard among Global Navigation Satellite Systems, DeLaPena said: “We’re the best in the world” in terms of accuracy, integrity, and availability.

But jamming and spoofing are growing challenges, highlighted by Russia’s aggressive electronic warfare in Ukraine as well as concerns about China’s potential to try to deny GPS access to U.S. and allied forces. GPS signals can be drowned out with powerful radio frequency signals broadcast at the same frequency, jamming the signals that users leverage to find their location.

The Pentagon has been working on countermeasures by upgrading GPS satellites, software, and receivers, but each effort has been plagued by its own set of delays.

Now the wait is almost over, DeLaPena promised. “All three of those lanes in the road … converge in 2025 and enable the warfighter to start depending and training with anti-jam,” he pledged.

Satellites

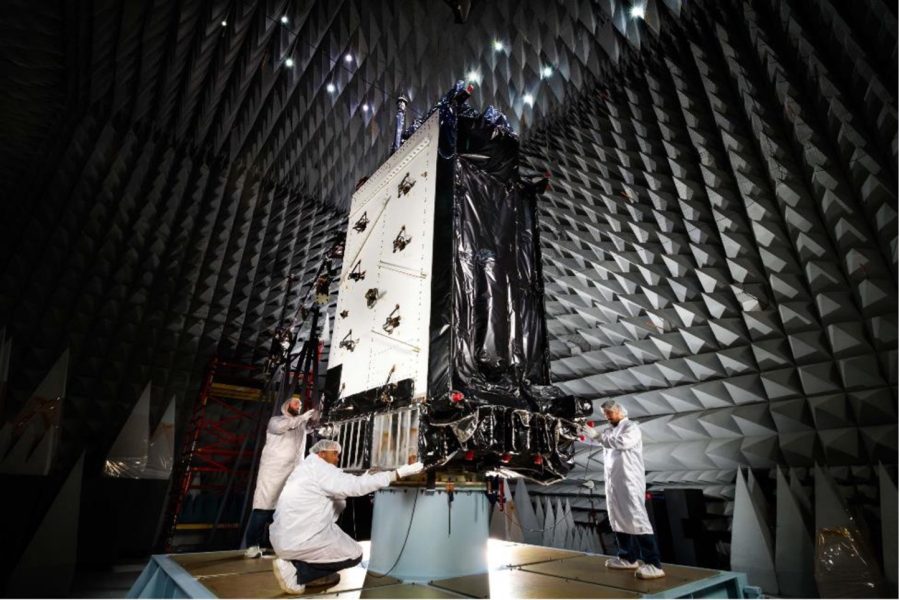

At the end of May, the Space Force plans to launch the eighth of 10 GPS III satellites, just a few months after launching the seventh spacecraft in the series. USSF is using a new rocket—SpaceX’s Falcon 9—and accelerating integration and readiness checks.

The seventh through 10th satellites in the constellation were built months ago and put into storage as the Space Force waited for the original launch vehicle, ULA’s Vulcan Centaur, to be certified.

The GPS III birds take full advantage of M-code, a more robust, encrypted, jam-resistant signal for military use. While other GPS satellites can transmit M-code, GPS III can beam the signal at target areas. But the real key is having a large enough constellation.

With seven spacecraft in orbit, “we have sufficient on-orbit capacity for anti-jam,” DeLaPena said. The remaining two satellites in the series will be launched over the next year and a half.

After that, comes GPS III Follow-On, which will have even better anti-jamming tech.

“The next era of anti-jam: a higher power, tighter beam called RMP, which stands for regional military protection,” said DeLaPena. “And because GPS is occurring in L-band, optimized for that orbit, we counter jamming by concentrating our power and we blast our way through it. That makes it very, very hard for our adversary to go against that power, because they’d have to build multiple, enormous jammers that are vulnerable in other areas as well.”

With M-code and RMP, the Space Force will be “almost all the way” to having a jam-resistant capability. Beyond that, DeLaPena said his office is exploring new technologies through contracts with the Space Force’s innovation incubator SpaceWERX.

OCX

While GPS III satellites started going up several years ago, the software system to control them proved bedeviling. The Next-Generation GPS Operational Control System, or OCX, has been a “tough, tough program,” said DeLaPena, who first started managing programs in 1990. “I’ve been in this business a while. … OCX is the hardest I’ve ever worked.”

Since contractor Raytheon was tapped for OCX in 2010, the program has been delayed again and again and even incurred a “Nunn-McCurdy” breach due to soaring costs.

Former Space Force acquisition executive Frank Calvelli called the failure to deliver OCX his biggest regret, but DeLaPena says it’s coming soon.

“Raytheon is scheduled to submit their DD-250 within the next 30 days, which will allow government testing and operational testing,” DeLaPena said, referring to the form that signals the Pentagon has accepted ownership of a system. “And the PEO will certify it’s ready to transition to operations by the end of the year. Huge milestone.”

MGUE

The last pieces in the puzzle are the terminals that receive the GPS signal. The Pentagon has been working on its Military GPS User Equipment program for more than a decade, another of the the programs Calvelli bemoaned as “problem children” in his portfolio.

The first increment of MGUE terminals are being tested now. “We’re flight testing with an Army UAV, we’re taking it to the jamming range. Next week, we’ll fly it against the jammers, and we’re scheduled to certify the final variants of MGUE Increment 1 in July of 2025,” he said.

MGUE is needed to receive M-code, making it part of the anti-jamming solution. And moving forward, DeLaPena said a second increment will help even more by allowing users to tap into position, navigation, and timing signals from non-GPS satellites.

“What increment two brings is incorporation of other PNT sources, not only just U.S. GPS, but it’ll incorporate some alternate PNT sources that the Army uses,” DeLaPena said. “It’ll incorporate international GPS, multi-GPS from space, things like from our allies, incorporating the Europe solution, incorporating the Japanese solution, and it’ll blend those solutions.”

The key to doing so is moving toward software-defined receivers, with antennas that can be reprogrammed quickly to tap into more signals. Flexibility in general will be key to future anti-jamming efforts, DeLaPena said.

“In the future, we’ll look at making sure that we’re not designing our anti-jam solution to be optimized just in one orbit in one waveform,” he said. “We need diversity in terms of the spectrum to allow flexibility into the other orbits as well, and a lot of that can come through these software-defined terminals that are being investigated across all the services.”