Northrop is moving into test and integration with a new software-controlled, multimode, “ultra-wideband” sensor that it said can simultaneously conduct radar operations, communications, and electronic warfare.

The new technology leverages the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s efforts to accelerate sensor upgrades, and could be intended for use on Air Force Collaborative Combat Aircraft or the Next-Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) family of systems.

Called EMRIS, for Electronically-scanned Multifunction Reconfigurable Integrated Sensor, the new device was designed to be “easily scaled and reconfigurable” across a variety of platforms, said Krys Moen, Northrop vice president for advanced mission capabilities. It employs an open architecture, she said, so “we can rapidly add new or improved capabilities to increase performance while avoiding redesign.”

EMRIS builds on DARPA’s Arrays at Commercial Timescales (ACT) program, which set out to break existing patterns in which sensor upgrades to 10 years to develop and remained in use for 20-30 lifespans, requiring costly service life extension programs. DARPA wanted to bring sensor array upgrades more in line with commercial upgrade cycles and narrow the widening performance gap “between the radio frequency (RF) capabilities of military systems and the continuously improving digital electronics surrounding those systems.”

Northrop did not identify any specific platforms for EMRIS, but the technology is compact enough to fit in a small drone. Rather than targeting “any particular program capture,” Moen wrote in an email response to questions, the EMRIS investment is intended “to enable earlier insertion into a variety of future programs.”

The architectures “are easily scaled and reconfigurable for a wide applicability across platforms and domains,” she said, and the sensor can be “either mounted in the nose of an aircraft or integrated within the skin of a platform.”

EMRIS could be retrofitted to existing platforms or designed into future ones, the company said.

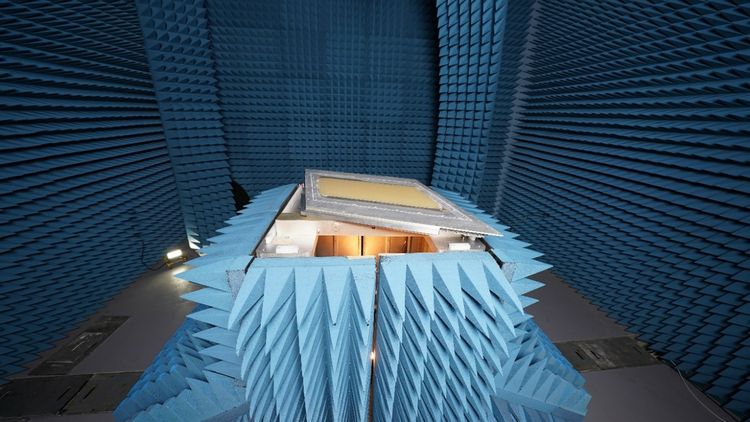

An image of the hardware under test in an anechoic chamber indicates a flat, trapezoidal aperture, suggesting the sensor could be flush-mounted on a flat surface or inside an aircraft’s nosecone.

The new technology consolidates “multiple functions into a single sensor, decreasing both the number of apertures needed and the size, weight and power requirements for the advanced capabilities,” Moen said. Those advantages also would lend themselves to reduced cost and complexity in an aircraft and improved stealth.

EMRIS was designed using common building blocks, Northrop said, which was among DARPA’s objectives in its ACT program.

ACT sought to create “a digitally-influenced common module comprising 80-90 percent of an array’s core functionality” that could be used in a “wide range of applications,” DARPA said at the time. Building blocks included “reconfigurable and tunable RF apertures for spanning S-band to X-band frequencies.”

Moen said EMRIS is flexible technology that will have numerous applications.

“We can scale the frequency range based on what a specific customer requires,” she said. “The multiple degrees of freedom allow EMRIS to respond to a wide range of threat systems through software updates.”

As threats evolve, she said, “so too does the software-enabled capabilities in the system.”