When seven Air Force B-2 stealth bombers hit Iran’s deep-underground nuclear development sites on June 21, the tool of choice in “Operation Midnight Hammer” was a unique weapon conceived and designed two decades ago for exactly such a mission: the GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator.

Built by Boeing, along with the Air Force and Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the MOP is a 30,000-pound, 20-foot-long behemoth that is 31.5 inches in diameter and includes a warhead weighing in at 5,740 pounds. The B-2s dropped 14 MOPs in the operation, which Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said was the first-ever operational use of the weapon.

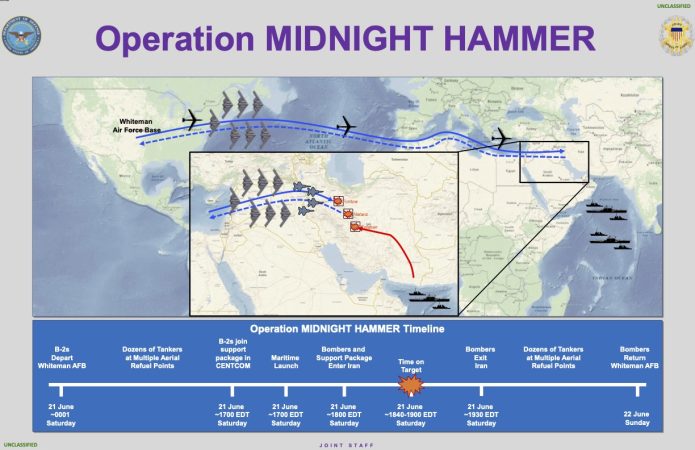

Seven B-2 bombers—each with two MOPs—took part in the operation, while two other B-2s flew in a decoy operation that gave the impression the U.S. was deploying its stealth bombers to Guam. This meant that virtually the entire flyable B-2 inventory—there are only 20 B-2s in all—took part in the operation.

Fourth- and fifth-generation Air Force fighter jets. joined the B-2s in the operation as well. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dan Caine did not say which platforms were used.

In all, Caine said “more than 125” aircraft participated in the mission, including the B-2s, fighters, “dozens and dozens of air refueling tankers,” and a “full array” of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft. In addition, “hundreds of maintenance and operational professionals” supported the operation, he said.

A Navy submarine in the Arabian Sea launched “more than two dozen Tomahawk land attack cruise missiles against key surface infrastructure targets at Isfahan,” Caine said. He added the TLAMs were “the last to strike” after the B-2s left the area.

Besides being stealthy and able to carry a heavy payload, the B-2’s radar allows it to map the target area in three dimensions with high resolution, and deliver ordnance very precisely against very specific aimpoints, such as ventilation shafts or other apertures.

A former B-2 pilot said that, once over the target area, B-2 pilots can use the radar to generate target coordinates “usually even more precise than intel has provided.”

B-2s have a rated maximum weapon load of 40,000 pounds, requiring special considerations to carry two 30,000-pound MOPs. The former B-2 pilot said the bombers likely took off with “a very minimal fuel load” and then refueled almost immediately after getting airborne. He said the B-2’s computer systems manage the aircraft’s flight so that, when the extremely heavy weapons are released, the aircraft doesn’t pitch violently upward, which might risk exposing it to tracking radars.

The MOPs were likely dropped from as high as 30,000 feet, sources said. Footage of MOP test flights show the bombs rapidly point nearly straight down after release, meaning the B-2s had to be virtually directly above the targets when the MOPs were dropped.

Developed beginning in the late 1990s, the MOP was inspired by U.S. defense leaders’ concern that work on nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons could be conducted out of reach of existing weapons in hardened, deeply-buried facilities. North Korea and Iran were both building such underground bunkers. While low-yield nuclear weapons were initially considered, U.S. officials worried that employing nuclear weapons would be considered escalatory and provocative.

In 2004, the Air Force and DTRA set about designing a conventional weapon capable of penetrating through layers of solid rock, steel, concrete and other materials to reach laboratories and storage facilities buried 200 feet underground. The GBU-72, a 5,000-pound penetrator rushed into service for use against Iraq during the 1991 Gulf War, could not reach those targets.

The MOP was designed with a hardened casing that, using gravity alone, would slice through protective layers of earth, rock, concrete, and steel. Inside the bomb, sensors can detect how many voids and layers it’s passing through and detonate at the chosen level.

It’s not known exactly how many MOPs were built. Public records suggest 20 were purchased, but nearly that number has been expended in tests.

Although it was initially tested with the intent of dropping it from a B-52, the MOP was always intended to equip the B-2 bomber since the heavily protected targets it was designed to hit were expected to be defended with top-tier air defense systems. Initial operational capability was achieved in 2011.

Test drops from B-2s were conducted in 2014-2016; four were tested in 2017 to validate enhancements. The most recent upgrade is the Large Penetrator Smart Fuse modification, which was tested in 2020 against a tunnel target. Three more tests were conducted between 2021 and 2022. Two full-scale tests were made in 2024 to verify B-2 integration work and lethality.

An Air Force fact sheet on the MOP describes integration activities for the weapon as “complete.” It said Boeing got the contract to complete integration of the MOP in 2009, which “entailed minor modifications to the MOP and to the aircraft.”

Other weapons likely employed in Midnight Hammer include:

ADM-160 MALD. Caine’s mention of “decoys” may reference the Raytheon ADM-160 Miniature Air-Launched Decoy, or MALD. The MALD is a low-cost missile that emits signals mimicking those of fighters and other combat aircraft, meant to fool air defense systems into shooting them instead of the crewed airplanes. The weapon has no kinetic mission, but is available in a radar-jammer version as well as the basic decoy model. The MALD has a range of about 575 miles and is most frequently carried by F-16s. If it were used in Midnight Hammer, it would mark the first combat use of the weapon.

BGM-109 TLAM. The 3,300-pound Tomahawk Land Attack Missile, also built by Raytheon, is a ship- or submarine-launched, GPS-guided weapon with a 1,000-pound blast/fragmentary or unitary warhead. The “D” model TLAM is a submunitions dispenser. It’s capable of precision attack against fixed targets, but it can be reprogrammed in flight to strike other targets. TLAMs fly at subsonic speeds at low altitude, evading defender radars by hugging the terrain. More recent models have a camera that will allow TLAMs arriving after some have already struck to transmit imagery of battle damage back to their launch platform.

AGM-88 HARM or AARGM-ER: Caine did not specify which “high-speed” defense-suppression weapon was used against the defensive missiles and radars around the three nuclear sites, but the Air Force has two such weapons. The AGM-88 High-Speed Anti-Radiation Missile, or HARM, was used to great effect in the 1991 Gulf War. It quickly detects a search or tracking radar, and when launched, follows the emissions at extreme velocity directly to the radar, destroying it. Iraqi radar operators quickly stopped turning on their air defense radars when it became clear that any emissions would result in an explosion a few seconds later. A defense official told Air & Space Forces Magazine numerous HARMs were used in the operation. The HARM’s successors are the Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile (AARGM) and the AARGM Extended Range, made by Northrop Grumman. Besides being less jammable, the AARGM can fly farther and faster, is stealthier to prevent it being shot down, and can better distinguish between targets. It will also be the basis of the Stand-in Attack Weapon (SiAW), which the Air Force expects will succeed the Joint Direct Attack Munition series of guided bombs.

Pentagon Editor Chris Gordon contributed reporting.