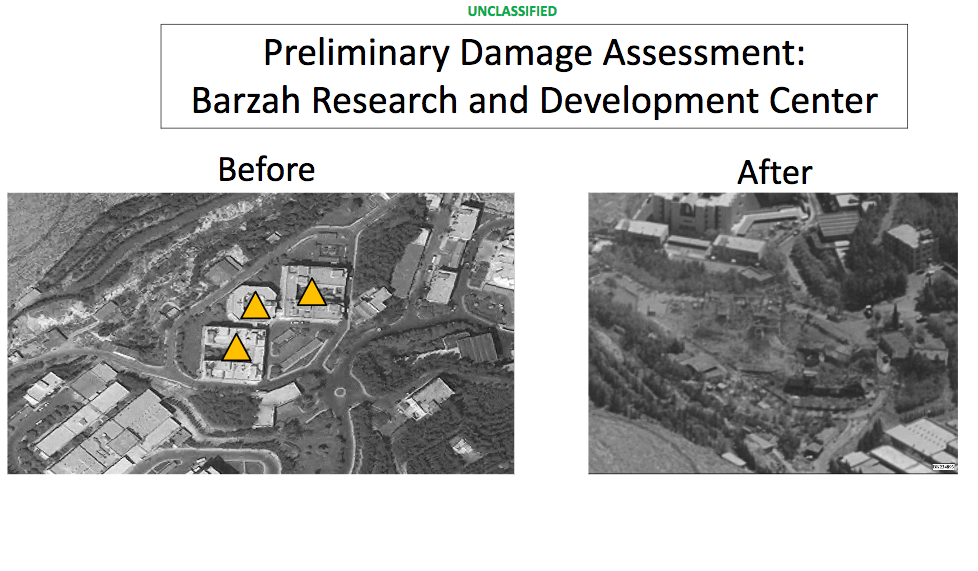

The Pentagon on Saturday showed reporters before and after pictures of the Barzeh research and development site, which was struck by a total of 76,000 pounds of explosive in a late Friday strike in Syria. Screenshot of Defense Department briefing slides.

Russian trolls have been dismissing the effectiveness of the US-Anglo-French strike on Syria’s chemical weapons infrastructure since the April 16 attack, saying, in effect, that if a true chemical weapons site had been hit, then any stored weapons at the facility would have been released, injuring or killing civilians in the area. No such release has been detected.

US officials have only said that the strike was designed to “mitigate” such a dispersal of toxic gases.

Asked what those ”mitigation” efforts may have been, Air Combat Command chief Gen. Mike Holmes, in an interview Monday, declined to comment specifically on the Syria situation, “because I wasn’t involved in it.”

However, “in generic terms,” he said, when attacking a chemical weapons site, the calculus involves “a thorough target study,” that models “the wind, the weather, and everything else.”

Then, “the weaponeering solution is to choose the right weapon and the right number of weapons, to reduce the risk” of a chemical weapon getting out.

Holmes advised paying close attention to the number of weapons employed against the target; numbers put out by the Pentagon itself on Saturday morning.

“Numbers matter in terms of reducing the risk of stuff being spread around, and how much you … burn up on-site.”

The Barzeh research and development site was struck by 57 Tomahawk Land-Attack Missiles (T-LAMs) and 19 JASSM-ER missiles, each with a warhead of at least 1,000 pounds of explosive, but with considerably more destructive effect, meaning the site was hit by more than 76,000 pounds of explosive. By contrast, hardened targets struck in the two Iraq wars were typically taken out by two 2,000-pound bombs.