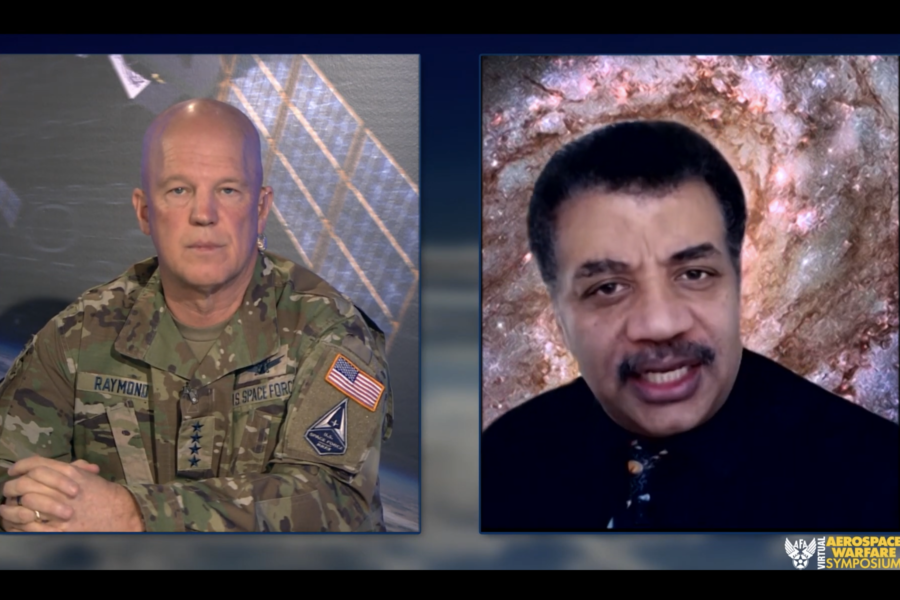

At the Air Force Association’s virtual Aerospace Warfare Symposium on Feb. 25, Chief of Space Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond laid out in plain language the serious threats facing U.S. and allied space capabilities. In a spirited discussion with renowned author and astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, the space Chief and the Scientist shared their common view of the value, opportunities, and vulnerabilities of space in the modern context.

Watch the segment or read the transcript below.

Chief of Space Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond: “Hey, Dr. Tyson, Jay Raymond. How are you, sir?”

Neil deGrasse Tyson: “Yeah, excellent. Sir, it’s great, it’s great, it’s great to see you.”

Raymond: “It’s great to see you as well, and I just want to, first of all, say thanks to the Air Force Association for providing us this venue, and more importantly I’d like to say thanks to you for agreeing to participate with me. I’ve had an opportunity to chat with you in person in your office, you are masterful at bringing very complex topics down so the average person like me can understand it and I couldn’t ask for better teammates here, so thanks for…”

Tyson: “Yeah, yeah, you’re an average person. Yeah, sure (laughing). Yeah, so I was, what I wanted to do was, if I could just sort of open up with some perspectives that I carry as a scientist, but also in a way, as sort of an emissary of the public, right? Because we just sort of watching, and rose up out of the, you know, from the firmament came the Space Force, at least that’s how people think of it, and I wanted to make sure that people understood. I think most in this audience know what I’m about to say, but if this gets posted online, it’d be nice to just sort of put it out there that many people’s first thought was that if the government creates a Space Force, then that’s a first step in the militarization of space. And all I can think of is the movies where there are sort of laser weapons and this sort of thing. And I’ve tried to remind people, or alert them, perhaps for the first time, that ever since Sputnik, space has been recognized as a strategic asset, or rather a strategic location. And so for the past 60 years, space has been the place for reconnaissance satellites, and, and navigation and, and so, so it’s not a new thing. It’s actually an old thing that is finally getting recognized in the way it needs to be, in terms of, within the, sort of the umbrella of national security. And I also try to remind people that, you know, often when people think of warfare and they think of space, they think of weapons and soldiers and armies and fighting, and, and they’re defending us, and I think to myself, well, it’s more than that. Of course, all right, wherever you have assets that you value, you will want to protect those assets, and who are you going to call, right? And if they’re national assets, you’re going to call a national, a national group to defend that, and that would be the Department of Defense. So, what do we have in space? We have satellites, of course, that monitor weather, climate, of course those are different: Your weather is what happens today and your climate are the trends over time. We have satellites that currently monitor, agriculture, checking rain. The, the humidification of regions and how that’s changing. We’ve got communication satellites, and of course, we have navigation satellites, among others. And when I think of communication satellites, you know, it’s not just, am I getting my live news broadcast from Europe? No. There’s like, Uber uses satellites, OK? So the value of our space assets is not just the cost of the design and launch of that one satellite, it’s the commerce it enables, which is rising through trillions of dollars of our commerce, and our economic stability. So, I can say to myself, OK, I don’t want anything bad to happen to that. And no matter where I am on the, sort of the peace-war spectrum, I don’t want anything bad to happen to that. And so, so at some point, we’ve got to turn to you, sir. And I’m going to ask you, do you foresee threats to our space assets? And because the total value is, is what I described, the total, meaning that it has to us in our way of life. So, do you foresee threats, and if you do, on what timescale, and are you equipping yourself to handle that? So I want to put that in your lap.”

Raymond: “First of all, I couldn’t agree more with, with your opening remarks. The United States has long known, long recognized that access to and freedom to maneuver in space is a vital national interest, as you said. It underpins our national security, it underpins our intelligence efforts, it underpins our treaty verification, it underpins our economy. And as you mentioned, there’s a growing, significantly growing economy in space between here and the lunar surface, estimates of over a trillion, trillion dollars over the next handful of years. It under, it underpins every instrument of national power, and we’ve long recognized that. The challenge is that the access to space and freedom to maneuver in space can no longer be treated as a given. It, it, we have to be able to protect, because there are threats that exist today. And if you look at it, China, which is the pacing threat, and Russia, and others, but primarily China and Russia, are doing two things that are concerning. First of all, they’re developing their own space capabilities to have the same advantage that we currently enjoy by integrating those capabilities into our, our way of war and our way of life. The other thing that’s very concerning is that they’re developing a spectrum of threats to negate our access to space, and they keep our nation, our allied partners, and, from being able to achieve those benefits. Let me put a little sharper point on that. Today—so this isn’t a future thing, this is today—there are robust sets of jammers that can jam both communication satellites and our GPS satellites, our navigation and timing satellites, if you will. Both China and Russia have directed energy weapons today. They have multiple systems that can, think lasers, that can blind or damage our satellite systems. Both China and Russia have missiles that they can launch from the ground and kinetically, kinetically destroy satellites in low Earth orbit in a matter of minutes. We saw that in 2007, very visibly, when China shot down one of their own satellites. Russia has a system called Nudol. It’s a similar system. It is designed to destroy satellites in low Earth orbit, as you said, where we have some pretty important capabilities. And both are developing capabilities on orbit that are concerning. I talked very publicly this year for the first time, about a Russian anti-satellite system. I referred to it as kind of like a nesting doll, where there’s a doll inside of a doll, inside of a doll. We’ve all seen those. Well, Russia launched a satellite right up next to one of our satellites, opened up, if you will, and released another satellite. We saw this before, this behavior before, a few years back. And that second satellite has the capability of releasing a projectile, and we know it is designed to kinetically, to kinetically destroy U.S. satellites in low Earth orbit. China, today, on orbit, has a satellite that has a robotic arm. That robotic arm can be used in the future to grapple, grab a satellite, if you will. And then there’s also cyber threats that we’re concerned about. So that threat spectrum exists today. It is very broad. It is robust that both China and Russia are continuing to develop those threats, and it’s something that we have to protect against today, and that’s why the establishment of the United States Space Force is so important. We are purpose-built to stay ahead of that growing threat.”

Tyson: “Yeah. How do you handle inquiries that sort of feel like the, the dandruff problem, and that’s the only way I can think about it in simple terms, where as you go up to someone after you learn they’re using a dandruff shampoo, and you say, you say to them, ‘Why are you using it? Why are you using a dandruff shampoo?’ You don’t have to answer it. They don’t have dandruff because they’re wearing, they’re using the dandruff shampoo. So I’ve got people saying, you know the world is basically at peace among superpowers, so, so why… will people take for granted that things are at peace, not knowing and not realizing that you’re there on the frontlines, maintaining that peace and our access to space. So how do you, how do you, how do you address that? Because they might say, ‘The budget is huge, it doesn’t have to be that big. We don’t need it.’ And, well, yeah, yeah, and do you need your dandruff shampoo, either, you know, I’ll take it away and watch how fast the dandruff comes back. So, yeah, how do you, how do you jump into that conversation?”

Raymond: “Yeah, well first of all, I’m lucky that I don’t have a dandruff problem, so I’ve got that going for me. (Tyson laughing). So thanks for bringing that up there, Dr. Tyson. Let me just say, it’s kind of like deterrence. Our, our primary mission is to deter conflict from beginning or extending into space. We don’t want to get into this fight, and if we can deter conflict from beginning or extending into space, we think we can deter conflict from spilling over into other domains. And so we want to do that from a position of strength. We cannot afford, you talked about the cost of space. If you look at the overall Department of Defense budget, the cost of space—although every taxpayer dollar is precious and every taxpayer dollar has to be spent wisely—the cost of space is a very, very small portion of the Defense Department budget. And oh, by the way, space is a huge force multiplier. Space enables us to do things with, that the other services can do with smaller force structures because they have integrated space to their advantage. We cannot afford, as a nation, to lose space. That’s why the space force is so important. We’re not going to lose space. We’re the best in the world of space, and we are running fast, the Guardians are running fast, to be able to stay ahead of that threat to determine from a position of strength and make sure that we don’t have dandruff.”

Tyson: “So, you comment that we are leaders, OK, that makes a good soundbite. But just moments ago you said that you’re noticing these capabilities, in particular, Russia and China and perhaps latter-day participants in space will, will also be so capable, and now we are responding to threats. So if we’re responding to threats, that means the threat pre-dated our capability. And I bring this up only because when we reflect on our history, exploring space, let’s go back to our golden age of space exploration, the Apollo era. We, as Americans, we reflect on that as, well, we’re explorers, we’re leaders, we’re Americans. ‘Mericans. And, but if you really unpack what unfolded over that time, the Russians, the Soviet Union, beat us at practically every metric that mattered at the time. You know, the first satellite, the first non-human, animal, the first human, the first space station, the first person of color—a Cuban person, of course in the, in the, in the communist bloc. The first docking for, you know, there’s so many things that they beat us at. And my read of that era is we were good at responding, because we were coordinated, we were not so tribalized, for example, as we are today. We said, oh my gosh, this is important. Let’s do this. And then we responded to each one of those threats, ultimately leapfrogging where the Russians left off. And we landed on the moon, and then we said, ‘OK, we win,’ but in fact, that’s not how that arc went. So, what assurances do we have that we’re going to stay out front, rather than sort of dragging behind, saying, ‘Oh we’ve got to do that, or let’s do that because they’re doing it.”

Raymond: “Yeah, so there’s, there’s no assurances. That’s why, that’s why this is, this business is so important. It is too critical to our nation to not be the leaders. And so, I would agree with you. I’d push back a little bit. We have been the leaders in space. We are the leaders in space. The end of the Soviet Union, we clearly have had, we’ve got the best capabilities, we’ve integrated those capabilities to great effect. GPS is the gold standard, for example, across the world. I mean, we have the best capabilities, and there’s no doubt about that. That threat has recently reemerged, if you will, over the last, you know, we saw in 2007 the visible detonation of a satellite, by the, by the Chinese, or destruction of a satellite from a missile launched on the ground. So now, although we have the world’s best capabilities, we now have a new mission area. And that’s that you can’t just launch a satellite, build a satellite, an exquisite satellite, launch it and assume that it’s going to be there forever. You have to be able to protect and defend it. That’s the new mission area. That’s why the United States made the decision to both stand up both the U.S. Space Command, the operational arm, the warfighting arm, and the Space Force, which is the, the organize, train, and equip arm. Where I think we lead, I think commercial industry, and you talked about this in your opening comments that, you know, the, the economic advantage that is provided from space. Our, our commercial industry is the best in the world. You look at what’s going on across commercial space, the U.S. is leading in that, in that business in almost every in almost every metric. If you look at our partnerships, the value of partnerships today is way greater than it was in the past. You didn’t need partnerships in the past, and our partnerships that we have with our closest allies are second to none in delivering advantage. And then I would suggest to you that, our people. We have incredible people in the Space Force, we have handpicked, handpicked every single person that came into this force. And if you look at what we’ve brought into the force, what we brought in are space operators, engineers, acquisition, intelligence, cyber and software coders. That’s it. It’s, every single person that was handpicked to come in this service has a role in deterring conflict from beginning or extending into space, and to win if, God forbid, if deterrence were to fail. Those people are spectacular. And in the Space Force, we took an opportunity to develop, because we’re starting with clean sheet of paper, we took an opportunity to develop a human capital strategy built for the 21st century, where we can bring in the talent of America, diverse talent, we can develop those folks, retain those folks, and, again, do that purpose-built for the domain in which they operate.”

Tyson: “Yeah. You make a really excellent point there that I want to sort of further develop here. So what you’re saying, I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but what you’re saying is that, as we move forward, our security will be measured not solely by how many missiles are packed in the silo, but how many scientists and engineers and coders you packed in, in the programming room. And so this is a change of the face of modern warfare, if you will. And if that’s the case, because I happen to know that scientists are cheaper than missiles. So if that’s the case, how do we continue to move forward with by far the hugest military budget in the world, that of the United States? How much of that is sort of legacy of how wars used to be fought, you know, let’s bring in the battleships, and bring in the marching armies, and if that’s not who’s threatening us today, what, what is going to happen to that budget as we go forward, or what’s your vision of that 10 years out, 100 years out?”

Raymond: “So first of all, if you look at the National Security Strategy and the national defense strategy, it outlines a very complex strategic environment, an environment that has global challenges, multidomain challenges. And, and, and challenges that move very, very fast, at great speeds and across great distances. When we decided to establish the Space Force, it was not just space for space sake. This was about our national security. It’s a national security imperative, and this is about making sure, as I’ve mentioned before, that we can stay ahead of that threat. I mentioned briefly earlier that, again, every taxpayer dollar is precious. Let me, let me give you a story to bring this to life a little bit. Back in World War II, the Air Force had 1,000 bombers to go with nine weapons, nine bombs on each bombers, so 9,000 bombs going after one ball bearing factory. And on a good day, about 100 of those bombs would strike close, somewhere close to the target. Look at where we are today. You can take off a bomber, with multiple weapons, and hit multiple targets all very, very precisely, and the way you do that is you integrate multidomain capabilities into that bomber—space and cyber. Again, that’s that, that advantage that that integration provides. So, if we lost space, do we have 1,000 bombers in our Air Force today? We don’t. So that’s why I said we can’t afford to lose space, and we’re not going to lose space. It’s too important to us. And most importantly, again, if we can assure our access to space, a vital national interest, then we are, feel that we can deter conflict from spilling over into the other domains, which we desperately don’t want.”

Tyson: “Thanks for that ball bearing example. That’s, I think, one to be repeated when that topic comes up. When I think of space, also, there’s a lot of sentiment in the public. These are people who don’t really do their homework, but just react to a news headline. The idea that, ‘Oh my gosh, now the military is going to weaponize space,’ and I tell people, there was a U.S. Space Command that was living within the Air Force. And so this, at least for the moment, was a horizontal shift, almost budget neutral. And just confirm if this is correct, a budget neutral shift, so that the Space Force can be thought of with its own priorities as we move forward. And it seems to me that greatly resembles what happened just after the Second World War, where the Air Force itself was a sort of a wholly contained sub branch of the Army, the U.S. Army Air Force, and then the Air Force sort of slid over to the side. And it was kind of obvious, you know, command and control was different, the training of the soldiers was different. And so no one questions that move today, looking back on it. And so I bring that to the face of people who were saying, ‘Why do we need an Air Force?” But would you agree with what I just said there.”

Raymond: “So first of all, I would say right off the bat, space is a warfighting domain just like air, land, and sea. And so an, example years ago, you know, we, we are a maritime country. And commerce and trade flow sailed over the oceans, if you will, and we had a Navy to be able to protect that ability to do that. The Army operates, best Army in the world, operates on the ground, on the land domain. We have an Air Force that operates in the air domain. And, as it has clearly been recognized that space is a warfighting domain, we now have a service that is focused on protecting and defending that domain, and all the benefits that we talked about upfront about that. We did have a service, we did. The Air Force was responsible for the vast majority of the space mission, although the Army has space capabilities and as the Navy, and there’s Marine capabilities as well, but the Air Force was largely, had the largest portion of that. And what the United States decided to do was to act on an opportunity, to not wait until we were playing catch-up, like your question from before. This was, ‘Let’s take the opportunity while we’re still ahead, while we’re still the best in the world at space, and focus this new service, to be able to move at speed. To stay ahead of that growing threat, and not respond to it. So what we’ve seen by elevating space to an independent service, that was largely resource neutral, there is no additional manpower associated here, this was all came out of hide, and the dollars spent to establish the Space Force were just a few 10s of millions of dollars. This isn’t, we’re not talking huge, huge budgets here this was largely taking dollars that existed and shifting it into, into this independent service. What it has allowed us to do, though, as you elevate that, it elevates the chief of the service as a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, it elevates our, our voice in requirements. It elevates our ability to compete for dollars to get resources for those capabilities that are so vital to our nation. It elevates our ability to develop our own people, and to attract and retain, assess, recruit, and retain those people. So on all metrics, we have seen just in this first year, significant increase and significant goodness by having this, this new service.”

Tyson: “I have more of a subtle question that just occurred to me in this moment. So, if you, you mentioned earlier how important our commercial space has been to what we are as a nation, and, and we lead the world. SpaceX most visible among them in leading this effort. And let me go back to the Second World War, where, OK, the Army needed Jeeps. OK, so they knock on Chrysler’s door and they say, ‘Can you turn this assembly line on,’ I’m simplifying here, of course, ‘and roll Jeeps off.’ OK, yes. And so that, there goes the contract, out come the Jeeps, and, and the military did not have to make their own automobile factory to do that. OK, so there are efficiencies that came about because of it. As we go forward, I will presume that that’s the kind of relationship the military would want to have with our, with our, the business base of our space assets here in the United States. But to the extent that businesses have become multinational, then it’s no longer sort of our own, our own assets is it? It’s sort of, it has consequences globally. So I’m just wondering, what does that look like going forward, if you want to reach for a company that that happens to also do business in China or, and or in Russia, and now they’re going to do some work for the military?”

Raymond: “So it’s a great, great question, and one that we’ve put a lot of thought on, and one that I think offers us a lot of opportunity. The first year of, of the argument, we’ve been, the Space Force was established 14 months ago, so we’re 14 months old, and when the initial planning was taking place, what we thought we were going to do was spend about 18 months planning for this Space Force, and then we’re going to stand it up. So if that was the case, I’d be sitting here today with you and I would say, you know in about three or four months, we’re going to, we’re going to actually start doing something. Well, we actually started 14 months ago we built an entire service in that period of time. And we, we’ve moved at speed. This second year is all about integration, and integrating this force. It’s driving the car that we built. And as we drive that car, the key pieces of driving that car is integration, and integration with commercial industry, integration with the interagency, and integration with our allied partners. And we think there’s huge opportunities in all cases. If you look at historically what has been commercially viable in space, it was commercial launch and large communication satellites. The barriers to entry to space and an increase in technology that allows smaller satellites to be more operationally relevant has now said that almost every mission that we do in space has a commercially viable path. And so, we want to build a very fused connection with commercial industry. We’re a small service, and we think we can do that, and with the, this is a terrible word to use in the commercial space business, but the explosion of commercial space things that are occurring, as you highlighted, provides us a great opportunity. The other big piece of this is that we have an opportunity with our allied partners. And so, in this first year of standing up an independent Space Force, we’ve also set up some partnership offices. And we have inked [a memorandum of understanding], for example, with Japan, to put a hosted payload on Japanese satellites, to provide capability at a reduced cost and increase the speed of when we can launch it. We did the same thing with Norway. We put, we’re going to put two communication payloads on two Norwegian satellites. It saved us over $900 million, just shy of a billion dollars, and will get us onto orbit sooner. And so as we design this force, and that’s one of the critical things that an independent service does. It, it designs its force structure. As we design that force, we want to design it in a way that capitalizes on this new business model that has emerged, that that produces satellites off of a production line, rather than the one-off, handmade wooden shoe that takes years and years and years to build. And we want to build this coalition-friendly from the beginning, to allow our international partners to invest, and we think that partnership is key to deterrence and key to our strength.”

Tyson: “Is there any thought given, I’m sure there is, but what kind of thought is given, to the 1967 Space Treaty. I read that treaty carefully. It’s very sort of Kumbaya, you know, it’s space will be a peaceful place. And when I first read it, I was, yeah, yeah, that’s how it should be, that’s the future. And then as I got older and a little more cynical, I thought to myself, you know, people can’t get along on Earth’s surface. What possible confidence do you have that just by going into space, everyone is going to be friends? And so I, I was saddened that I came to that realization, but that’s, you know, given the tribalism we’ve seen, especially in recent years, I don’t really believe that space can be thought of as a peaceful domain until that’s demonstrated to happen here on Earth’s surface. My point then to you is, I do remember there was one cause, or one phrase, that allowed the peaceful use of outer space to include the capacity to defend your assets. So, is anything the Space Force doing today in violation of the Space Treaty, or is there a new space treaty that’s going to be necessary for the 21st century? How much, what kind of thinking is, is, along those lines? I think of it almost like the Geneva Convention, as an attempt to guide the, the principles and engagements of war.”

Raymond: “So today, Dr. Tyson, space is the wild, wild West. There really is no rules. The Outer Space Treaty that you mentioned basically says you can’t put a nuclear weapon in space, or weapons of mass destruction in the domain, and you can’t build military bases on planets, and that’s about it. Beyond, besides that it’s the wild, wild West. I get asked a lot, I frequently get asked, you know, what, as you are establishing this service, what capabilities do you want your successors to have? And my first answer to that, besides capabilities, is I would like my successors to have some rules of the road, on how you operate in space. It is not safe and professional for Russia to put a, a threatening satellite in close proximity to a U.S. satellite. That’s not responsible, safe, professional behavior. And so, we’re working with our partners to develop these norms of behavior. We’ve been exercising this, we’ve been wargaming it. We’ve made some really good strides, and we operate to demonstrate that good behavior. We operate in a way that demonstrates that we’re not violating any treaty. In fact, we’re the most transparent and voluntary service in the world in space, we share data broadly, we warn China that they’re about to hit a piece of debris that they created when they blew up their satellite in 2007. We want to keep that domain safe for all. And so I really believe there’s an opportunity here to, to develop some norms of behavior. Now I’m not naive to think, as you’ve stated in the question, that those norms of behavior are going to, you know, solve all the, all the ills that might occur in that domain. But I do think it will help us identify those that are running the red lights as we drive this car. And I’m hopeful to, I’m hopeful to be able to, working with our allies and partners to develop some norms of behavior that we operate with today, and will continue to operate with tomorrow.”

Tyson: “Sir, you need the trust but verify, you need red light cameras up there, and if anyone runs the red light, you’ve got them, and you know exactly where they’re coming from and where they’re going. I want to highlight something just, again, I think anyone listening live to this wouldn’t need this exposition, but I think some others might. You mentioned directed energy weapons versus kinetic weapons, and directed energy, I can actually characterize all of the history of warfare in one sentence. OK, it’s: I have energy over here, and I want to put it over there. That is the decision any warfighter makes, for every, practically every decision, for every action they take. From, from a bow and arrow, I have energy here in, you know, cocked into the string, it goes to the arrow, the arrow takes the energy to a target. Same for a bullet. Same for a missile, same for any of this. So, in a directed energy weapon, you’d have a laser or some other electromagnetic pulse, it sends energy from one point to another, and a kinetic kill, a kinetic impact is, the object, your weapon is moving so fast it does not need an explosive in order to do damage to its target, because the kinetic energy is sufficiently high to do whatever it needs to do on impact. So just as a, that’s my preamble to my question to you. It seems to me that a directed energy weapon keeps the satellite intact, you just sort of disabling a circuit board or something, or jamming it, whereas a kinetic weapon makes a big mess in space, and I’m thinking to myself, it makes a big mess, that would take us out, but it would also take out any adversary, because you’re not controlling where all these little bits and pieces are going. And so, all I can think of is in the First World War, when someone says, I have an idea, let’s use chemical gas weapons. Yeah, what an idea. So then they spray it onto the field, and then the wind direction changes and it comes right back at you, and then it becomes, OK, let’s rethink that one. So, so, I don’t know, I guess this isn’t the question, I’m just sort of putting it in your lap: Why does anyone want to completely destroy a satellite if it if it contaminates the sandbox for everybody?”

Raymond: “It’s irresponsible behavior. We don’t want that to happen, and that shouldn’t happen. If you look at the 3,000 pieces of debris that was caused back in 2007, we’re still tracking that. It’s in low Earth orbit. It’s in, it’s in the orbit that the International Space Station is in. And so we work very hard each and every day, we act as the space traffic control for the world. We track 27,000 objects in space today. There’s probably about a half a million that we can’t track because they’re too small. Of that 27,000 objects, about, just shy of 4,000 now are active satellites. And if you think about it, when I last talked to you on “Star Talk” just a couple years ago, the number of satellites were 1,500. And if you look at where this is going with, with proliferation of low Earth orbit satellites, you know, you’ve got the company you mentioned, SpaceX, with the, with their proliferated LEO constellation has over 1,000 satellites on orbit now, and that’s, that’s just been launched this year. So if you look at the numbers that are happening, that are being launched, it’s getting more congested, and the trends are going up significantly, because there’s other companies, as you mentioned as well. So we are all about keeping that domain safe, we do not want, again, to get into a conflict that begins or extends in the space and, and we would encourage responsible and safe behavior in the domain, just like we do in the air domain and on the sea.”

Tyson: “Yeah, I’ve got to emphasize something you just said, all right, you just said, that, you gave a number of stuff you’re tracking in space, and some small fraction of that number were active satellites, which means most things you’re tracking is junk, junk in space. And I joked that, you know, the reason why we haven’t been visited by aliens is because they saw the junk that’s in orbit around the Earth, they said we’re not going to land there, they’re going somewhere else. So, let me just ask then, if I were to, sort of, put on your portfolio, things that it’d be nice if the Space Force made a priority, it might be to sort of clean up space. I know you don’t want to be thought of as sort of the sanitation workers of space, but if the space domain is something we all care about, then, inventing some innovative way to get the debris out of space could be something very useful for the future. And I want to add to that. What about asteroid defense? So I hear you’ve been protecting the whole world, not just the United States, and that’d be the noblest thing you could possibly do, in my biased humble opinion.”

Raymond: “I would agree. We want to keep the domain safe and limit debris. And I think if you and I could figure out a way to clean up all that debris that’s moving so fast and over those vast distances, let me know, and I’ll invest with you, because we’ll be well off.”

Tyson: “I’ll get to work on it now.”

Raymond: “What we are doing, and one way to solve the debris problem is not to create to bring in the first place. So, you know, warning people about potential conjunctions, having better engineering standards, so satellites don’t break apart at the end of life, having better launch standards so when you launch rockets into space, you don’t also litter the domain with debris, and so we’re working a lot with that. We also signed [a memorandum of understanding] on the asteroid work, we’ve signed an MOU with NASA to share information more broadly. That largely falls in their, in their mission set, but I do think there’s partnership opportunities and we’re working on that. I know we’re getting really close on time, and if you would allow me to turn the table, I want to ask you a question if you could.”

Tyson: “Oh, I’m sorry, I hogged all the time. It’s not every day I’m, in, you know, hanging out with you, so, OK, bring it on.”

Raymond: “So here’s the question for you: When I was up in New York with you in your studio for “Star Talk,” you are masterful at bringing the very complex down to easily understandable ideas. One of the challenges that we face in space is that, we have a saying, that a satellite doesn’t have a mother. You can’t see it, you can’t touch it, you can’t feel it, you know, it’s hard to have that connection, but that connection is really real. How would, how would you suggest that we communicate this thing that’s not tangible better to the American people so they understand just how reliant they are, and just how vulnerable those capabilities are, if we don’t protect and defend?”

Tyson: “OK, here’s what you do: You get “Saturday Night Live” to do a skit where they systematically remove things from a person’s livelihood and life, and home life, that was enabled or empowered, or, or conceived, for our having access to space. And basically by the end, they’re left in a cave, you know, sending smoke signals or something. I mean, I think it wouldn’t, you don’t have to be too clever in the marketing of this fact. I hate the word marketing because it implies you’re, you might say something that’s not true, but everything that you say would be true about what it is you can no longer do, in modern time, that we all take for granted. And so it’s a matter of moving what we take for granted into something that’s front and center in our lives. And by the way, the fact that we take it for granted, that’s overall a positive fact, because it meant we’ve absorbed it into our existence, and it becomes transparent to how we live our lives. I don’t have a problem with that, but if you simultaneously stand in denial of its value to you, that’s, that’s where the problem is. So yeah, it’s your, is it an ad campaign? I don’t know, I’m out there trying to do it. So maybe we need more.”

Raymond: “OK, sir, I’ll tell you what. I’ll join you on the stage at “Saturday Night Live.” You work the invite, and I’ll be there with you. Sir, I can’t thank you enough, it’s always it’s always a pleasure to chat with you, I really…”

Tyson: “Can I get to one last, I know we’re running short on time, I just, who introduced us? Orville Wright introduced us? What, what? Someone named Orville Wright? OK, and so I was looking at my notes and I actually own an original letter from Orville Wright, and I’m assuming the gentleman who introduced us is not 150 years old. So if you give me a moment here to share my screen, I want to show you a letter written by Orville Wright, and here it goes. I think I’m doing this right. I’ll read it to you. December 19, 1918. Orville Wright, Dayton, Ohio. And this is a letter to the president of the Aero Club, Aero Club of America, and here it goes. ‘My dear Mr. Hawley, Thank you for your very nice telegram remembering the 15th anniversary of our first flight at Kitty Hawk. Although Wilbur, as well as myself, would have preferred to see the airplane developed more along peaceful lines, yet I believe that its use in this great war will give encouragement for its use in other ways.’ And so let me end screen share there. So I put that up to make the following point, that I don’t, I know of no force operating on the ambitions of a next generation, than people looking up into the night sky, and thinking, what is there, how can I participate in its discovery? The entire STEM spectrum, science, technology, engineering, and math is all represented there, and these are the fields that when they’re stoked in an economy, will generate the entire next generation of economic value to a nation that embraces it. So for me, the Space Force can lead the way in people’s ambitions to want to, to want to, to want to create a future that we all dreamt of, and somehow, has not yet arrived.”

Raymond: “Yes sir. That’s a great, great way to wrap it up, sir. Thank you very much. It’s been an honor to serve, share this virtual fireside chat with you.”

Tyson: “Thank you.”