A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carries an Iridium satellite into orbit from Vandenberg AFB, Calf., in January. Photo: SrA. Clayon Wear

QUESTIONS REMAIN AS LAWMAKERS MULL SPACE FORCE PROPOSAL

By Rachel S. Cohen

Some lawmakers on Capitol Hill are confident an agreement on how to create a Space Force is within reach, although the path forward remains murky.

In the nearly two years since Alabama Republican Rep. Mike Rogers and Tennessee Democrat Rep. Jim Cooper rolled out a Space Corps proposal, the idea has picked up steam, thanks to continued congressional debate, President Donald J. Trump’s support, and the Pentagon’s formal Space Force proposal.

That plan calls for a separate Space Force within the Department of the Air Force. The new organization would encompass Army, Navy, and Air Force space groups, instead of limiting changes to Air Force Space Command as the initial Space Corps proposal asked.

“If we have legislation passed this year by the Congress, within 90 days we would stand up a space staff in the Pentagon with 200 people,” Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson said.

But right now, it’s unclear what legislation Capitol Hill may consider to organize, train, and equip space warfighters.

The Pentagon submitted draft bill text to lawmakers in February as part of its formal Space Force proposal, drawing mixed reviews.

Cooper, who chairs the House Armed Services strategic forces subcommittee, recently called the Defense Department’s version “about as close to our original House proposal as you can get.” It is more modest than Trump’s “over-the-top” idea for a new military department, he said. Trump has supported the idea of a Space Force within the Department of the Air Force, though he’s also made it clear he’d eventually like to see the service become its own department.

“You can quibble about this element of the bureaucracy or that, but the key principles, I think, are there,” Cooper said March 20 at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “We’ve got to have an unrivaled space capability, and I think we’re on track to make that happen.”

He told reporters later that day there’s a “greater chance for Senate acceptance than we’ve ever had before.” The case for a Space Force is “overwhelmingly strong, he said, and “we’re going to win.”

But HASC Chairman Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.) later criticized the plan for creating too much bureaucracy and vowed to explore other legislative options.

“It seeks to create a top-heavy bureaucracy with two new four-star generals and a new undersecretary of the Air Force to oversee a force of approximately 16,000 people,” Smith said in a press release. “It requests an almost unlimited seven-year personnel and funding transfer authority that seeks to waive a wide range of existing laws—all without a detailed plan or analysis of the potential end state or cost.”

Politico reported that Rep. Rick Larsen (D-Wash.) expects the HASC will revive its first Space Corps proposal instead. A spokeswoman for Smith declined to comment on the possibility of bringing back old legislation and told Air Force Magazine it’s premature to discuss details.

While Larsen suggested Trump’s support for a Space Force has made it politically difficult for Democrats to move forward, Cooper argues his stake in the matter could help bring bullish senators on board.

Rep. Mike Turner (R-Ohio), ranking member on HASC’s strategic forces subcommittee, believes lawmakers could find common ground somewhere in between.

“The original proposal had [too few] details and this one has so many constraints and additional resources concerns that somewhere in the middle is obviously where we’re going to have to land,” Turner said in an interview with Air Force Magazine, without identifying possible must-have or red-line issues.

Growing the Pentagon’s already-behemoth bureaucracy is a sticking point on both sides of the aisle, in both chambers of Congress. But it may also be an area lawmakers could smooth out.

Senate Democratic Whip Dick Durbin (Ill.) invoked the late Arizona Republican Sen. John McCain when asking Air Force leaders whether a potentially “uncontrollable” bureaucracy is in America’s best interest.

“[McCain] basically pushed back against the creation of brass and bureaucracy, saying, ‘Let’s put an end to the capabilities and readiness of the people who are serving our nation already,’” Durbin said at a March 13 Senate Appropriations defense subcommittee hearing. “I don’t want to rain on this Space Force parade, but I do think we ought to have a cold day of reckoning here, in terms of whether this is something which we will come to regret.”

Todd Harrison, a defense budget analyst at CSIS, said one area Congress could tweak is how much discretion the Space Force proposal allows the Defense Secretary to determine which DOD groups will transfer in and when in the next five years they will do so.

Another frequent concern is the long-term price tag. The Pentagon argues growing the Space Force over the next five years will cost $2 billion, including $72 million in fiscal 2020, and about $500 million each year once the organization is fully established. That amounts to “dust” in the overall Pentagon budget at a time when the US needs to dominate in space, protect those assets, and improve acquisition, Cooper argued.

While Cooper believes the government is “well within the ballpark of reasonable compromise” on the cost, Turner asserts the price “seems relatively high.”

“Where are costs being created as a result of duplication and where are they giving us increased capabilities and functions?” Turner said. “I’m not eager to cut a $2 billion check just to create a separate Corps to do what we’re already doing.”

At a Senate Armed Services strategic forces subcommittee hearing, Sen. Angus King (I-Maine) requested that Kenneth Rapuano, the assistant defense secretary for homeland defense and global security, submit a short memo justifying the change and outlining its “tangible benefits.

“Are you coming before us, saying, we can’t manage this now and we need to spend half a billion dollars a year?” King asked. “Convince me that this makes some sense.”

Lt. Gen. David D. Thompson, vice commander of Air Force Space Command, tried to reassure King the new force would help unify space capabilities spread across the department.

“I would also look at it as not just [as], ‘are we trying to fix a problem?’?” Thompson said. “It’s a question of, is the nation prepared, and are we organized to accept and take on the challenge that comes with space as a warfighting domain?”

Others—including the Air Force Secretary—have questioned how to avoid duplicating efforts, particularly when looking at how the new Space Development Agency could cut into the Air Force and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s work.

Cooper believes those disputes simply amount to turf wars.

“Let’s get it going here,” he said. “The person who most recently said the SDA is irrelevant or redundant will soon be leaving. I think that will clear a path for more positive thinking.”

Turner dismissed the notion that Wilson’s impending return to academia raises any red flags about where DOD’s space reorganization is headed. Wilson resigned, effective May 31, to become the president of the University of Texas at El Paso after two years as the service’s civilian leader.

“She’s a very good friend of mine, and she said that she had a very important professional opportunity that she anted to pursue, and I believe her,” he said.

Air Force Research Laboratory’s Skyborg drones will push artificial intelligence research. Photo: AFRL

MEET THE FUTURE UNMANNED FORCE

By Rachel S. Cohen

Two new autonomous aircraft concepts that promise to redefine the Air Force’s unmanned fleet are moving forward.

The first is Kratos Defense & Security Solutions’ XQ-58A Valkyrie, an experimental “wingman” aircraft that would fly alongside manned combat jets. The second, still on the drawing board, is Skyborg, an autonomous drone prototyping program launched in October at the Air Force Research Laboratory. The goal: Create a low-cost, easily replaceable, combat-ready system by the end of 2023.

Will Roper, assistant secretary of the Air Force for acquisition, technology, and logistics revealed the program in March, saying the new aircraft must be able to take off and land autonomously, fly in bad weather, and avoid other aircraft, terrain, and obstacles. The “modular, fighter-like aircraft” serves as a springboard for more complex artificial intelligence work, according to a March 15 request for information.

“Skyborg is a vessel for AI technologies that could range from rather simple algorithms to fly the aircraft and control them in airspace, to the introduction of more complicated levels of AI to accomplish certain tasks or subtasks of the mission,” Matt Duquette, an engineer in AFRL’s aerospace systems branch, said in a press release last month.

An experimentation campaign for autonomous airborne systems is in the works for fiscal 2019 and 2020, the RFI said. The Air Force did not offer more details about the campaign by press time, nor did it answer whether Skyborg is related to another AFRL endeavor launched last year that sought to develop an autonomous fighter jet by the end of 2019.

The XQ-58A Valkyrie demonstrator completed its inaugural flight March 5 at Yuma Proving Ground, Ariz. Photo: SrA. Joshua Hoskins

A similar program, Kratos’ XQ-58A Valkyrie, completed its first flight test March 5. The 30-foot-long, experimental “wingman” aircraft will fly five tests in six months to vet system functionality, aerodynamics, and launch and recovery systems, according to the Air Force.

Valkyrie is designed for long-range strike and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions. It performed as expected during its 76 minutes airborne at the Army’s Yuma Proving Ground.

“There are no specific restrictions for what it can or cannot pair with,” a company spokeswoman told Air Force Magazine last month. “The flight performance envelope matches the high subsonic and high G capability of fighter aircraft.”

Kratos plans to sell the drone in bulk for about $2 million per copy when bought in quantities of more than 100. Three aircraft will be complete this year. They declined to comment on future development spirals and production.

About two decades ago, the MQ-1 Predator changed modern warfare by allowing the military to hunt its targets from afar, prompting a slew of operational, legal, and cultural questions. Now the Air Force wants to push the envelope again.

New uninhabited aircraft ideas—whether low-cost, attritable wingmen, swarms, or stealthy designs that fly alone—are gaining traction in the era of great power competition. While Air Force drones have largely been used for air strikes and intelligence gathering in the past two decades of counterterrorism, new technologies are opening up possibilities for a more diverse, unmanned fleet that builds on missions flown today by the MQ-9 Reaper, RQ-4 Global Hawk, and classified UAVs.

“It looks like a very positive shift by the Air Force toward embracing the technology,” Paul Scharre, director of the Center for a New American Security’s technology and national security program, told Air Force Magazine. “The Air Force has been there on paper for a while, dating all the way back to the 2009 Air Force UAS flight plan. … It hasn’t necessarily really had the follow-through on this technology in the budget.”

Scharre, a former staffer in the Office of the Secretary of Defense and Army Ranger, believes aircraft like the Valkyrie are the future of American airpower.

“We’re basically looking for an Air Force that will have three versions of combat aircraft … F-35, F-22, and B-21,” he said.But “diversity is really helpful to complicate things for the adversary.”

Cheaper, attritable aircraft can help as the service tries to limit its number of procurement programs and drive down production costs, he continued.

Retired Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, head of AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, argues Skyborg and Valkyrie wouldn’t step on the toes of existing unmanned assets.

“They have the potential for dramatically changing the game in the conduct of air operations,” he said. “They can bring … more force inventory at a fraction of the cost of inhabited aircraft, while facilitating the employment of dramatically increased weapons employment capability over a much shorter timeline than required with conventional aircraft.”

Nor does he expect this will mark an era when human pilots always get an unmanned sidekick.

“The spectrum of air operations spans from disaster assistance/humanitarian relief to global thermonuclear war—there are many missions across that spectrum of operations that will require manned aircraft without ‘uninhabited loyal wingman’ flying with them,” said Deptula, a former Air Force deputy chief of staff for ISR. “That said, there will be a large portion of combat air operations” that will need drones, he noted.

These platforms are meant to help, not replace, the human brain, Scharre added. They can be flown closer to enemy air defenses and sent out on longer missions than legacy manned platforms. Drones could also play a new role as decoy, electronic-warfare, and kinetic strike missions.

“We’re likely to move over time toward a world where you see the human-inhabited aircraft play a sort of quarterback role where they’re managing the fight, but out at the edge, you actually have a diverse mix of uninhabited aircraft of various shapes and sizes,” Scharre said. “Some of them will be low-cost, attritable ones. Some of them will be more capable stealth aircraft that are probably fairly expensive, and there’s probably a role for them as well to do things like long-endurance surveillance or time-critical strike.”

He expects unmanned aircraft missions will shift to encompass more than primarily surveillance. Modularity would allow them to carry a wide range of sensors and weapons for different combat environments and to be deployed in unique combinations with other platforms.

It’s too early to speculate on what the right mix of unmanned aircraft might be as these platforms mature.

“It will probably take a generation, but the balance of human-inhabited and uninhabited aircraft in the Air Force should shift over time,” Scharre said. He expects that ratio could reach 20 unmanned aircraft to every one manned aircraft. For instance, each F-35 could have dozens of autonomous partners to make it more capable in battle.

“I love leather jackets and fighter pilots, but that’s not the future,” said Rep. Jim Cooper (D-Tenn.), the House Armed Services strategic forces subcommittee chairman. “Unmanned aircraft, as we’ve seen with drones, are increasingly important in the world.”

Deptula argues the service already embraces manned and unmanned forces as equals and hopes the service simply picks the right system for a mission, regardless of pilot or domain.

Scharre said there’s more work to be done. Over time, uninhabited aircraft may become the default as operators grow to trust them, as command and control technology improves, and as bureaucratic and cultural hurdles fall.

“I don’t know that they’re quite there yet,” he countered. “I think it’s where they need to get to over time. I think when you look at the bulk of the expenditures … the Air Force is still oriented toward short-range, tactical fighter aircraft. They haven’t even really made the pivot toward longer-range, persistent surveillance and strike aircraft.”

FOR USAF BASES, HARD CHOICES FOLLOW STORMS

By Rachel S. Cohen

Recovering Tyndall AFB, Fla., and Offutt AFB, Neb., will require $1.2 billion in fiscal 2019 and $3.7 billion across 2020 and 2021, and lawmakers were still searching for a solution at press time.

Without supplemental funding, Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson warned, USAF will have to move funds from projects at other bases.

Wilson has already pulled more than $250 million from 61 projects at 33 installations in 18 states to pay for rebuilding efforts at hurricane- and tornado-ravaged Tyndall. Those suspended projects include runway and roof repairs, dormitory renovations, laboratory demolition, and heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning system updates, according to a list provided by the Air Force.

The base needs about $1 billion by the end of September for operations and maintenance projects, as well as to plan its next steps. In the absence of additional funds, more cuts could come each month.

“The Air Force will make funding decisions based on the resources we receive,” service spokeswoman Ann Stefanek said April 1.

Without additional money, the Air Force predicted it would stop all new recovery work at Tyndall on May 1 and pause aircraft repairs across the service on May 15. Recovery at Offutt, “with the exception of immediate health and safety needs,” would be stymied as of July 1, and 18,000 flight training hours across the service would be cut starting Sept. 1.

Offutt was still partially underwater in early April after severe storms caused flooding. The Air Force said it immediately needs $350 million in 2019 for facilities sustainment, restoration, and modernization.

Offutt’s needs are yet to be fully determined.

Although topline numbers differed between the House and Senate, the main spending package under consideration on Capitol Hill earlier this year included $400 million for Air Force operations and maintenance. Another $700 million for military construction could be used for recovery efforts until Sept. 30, 2023.

However, the service wouldn’t be able to tap into the funds until it sends House and Senate appropriators a “basing plan and future mission requirements for installations significantly damaged by Hurricane Michael.” A “detailed expenditure plan” for the money would be due within 60 days of the bill’s enactment.

“I don’t think most of the members of Congress recognize the damage that’s going to be done to the Air Force and our military readiness, much less the public,” Rep. Austin Scott (R-Ga.) said April 2. “This is ridiculous. Obviously, there is partisan politics going on over there, but the truth of the matter is, the President could have done more to help with this before now.”

A congressionally mandated climate change report published in January acknowledged that the Pentagon needs to “better understand rates of coastal erosion, natural and built flood protection infrastructure, and inland and littoral flood planning and mitigation.” DOD says it must better understand the impact of sea level rise, storm surges, and floods, and how they can approach building differently to avoid weather-related damage.

Neither Tyndall nor Offutt were among the 79 facilities considered in the report, of which 10 were identified as most at risk for weather-related damage:

- Hill AFB, Utah

- Beale AFB, Calif.

- Vandenberg AFB, Calif.

- Greeley ANGS, Colo.

- Eglin AFB, Fla.

- Patrick AFB, Fla.

- JB Andrews, Md.

- Malmstrom AFB, Mont.

- Tinker AFB, Okla.

- Shaw AFB, S.C.

- JB San Antonio, Texas

USAF has created a task force to consider weather as an adversary. The group will look at weather forecasting and how to improve its models.

“The Air Force fights from its bases. They are our platforms for power projection. The Navy fights from its ships, the Army deploys forward and goes other places,” Wilson said. “When we plan our bases and look at things, the resilience of the bases, the duplication of power sources, the hardening of our assets” is critical.

The DOD report did not project what the Pentagon might have to pay to recover from and prepare for supercharged storms, expansive flooding, and other effects.

“The statute required each service within the department to assess the top 10 military installations that are most vulnerable to climate change over the next 20 years and detail specific mitigation measures—including their costs—that can be taken to ensure the operational viability and resiliency of the identified installations,” Reps. Adam Smith (D-Wash.), Jim Langevin (D-R.I.), and John Garamendi (D-Calif.) wrote to Acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan in January.

The report also left out Marine Corps bases and threats to overseas installations.

“It is relevant to point out that ‘future’ in this analysis means only 20 years in the future,” the January report noted. “Projected changes will likely be more pronounced at the mid-century mark; vulnerability analyses to mid- and late-century would likely reveal an uptick in vulnerabilities” unless mitigation strategies are put in place.

THE WAR ON TERRORISM

CASUALTIES:

As of April 5, 66 Americans had died in Operation Freedom’s Sentinel in Afghanistan, and 76 Americans had died in Operation Inherent Resolve in Iraq, Syria, and other locations.

The total includes 137 troops and five Department of Defense civilians. Of these deaths, 66 were killed in action with the enemy while 76 died in noncombat incidents.

There have been 386 troops wounded in action during OFS and 77 troops in OIR.

MSgt. Arenda Jackson marshals a KC-46A onto the flight line at McConnell AFB, Kan. The first Pegasus was delivered to McConnell Jan 25, but USAF has halted delivery of the tankers twice due to problems with foreign object debris. Photo:A1C Alexi Myrick

USAF REVIEWS TRAINING AFTER MAX 8 CRASHES; KC-46 USES DIFFERENT VERSION OF MCAS

By John A. Tirpak and Brian W. Everstine

The Air Force is reviewing its emergency training procedures and analyzing past autopilot-related mishaps following two crashes of new Boeing 737 MAX 8 aircraft, but it doesn’t believe its KC-46 tanker—which has a similar Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS)—currently endangers military aircrews.

Chief of Staff Gen. David L. Goldfein has “directed Air Force leaders to ensure we have adequate training in our aircraft emergency procedures and simulator training,” Air Force spokeswoman Ann Stefanek said in an email. “As far as autopilot systems, most USAF aircraft have some version of autopilot, with varying levels of complexity. At this time, the [Air Force] has no indication of problems with Air Force aircraft similar to what has been reported with the MAX.”

The Air Force is awaiting the results of a Boeing review of the 737 MAX 8 MCAS system, and “if there are any findings that affect the KC-46, the Air Force will take appropriate measures to address the findings,” asserted an Air Force statement. “The 767 family has not been impacted” by the MCAS issue.

Boeing was criticized during the KC-X competition for cobbling together a “Frankentanker,” as its competitor Airbus charged, using physical elements and software from several different aircraft to develop what became the KC-46.

The 737 MAX 8 uses an MCAS to deal with weight and balance issues driven by the narrow ground clearance of its engines. It will automatically direct a nose-down attitude to prevent the aircraft from stalling if the angle of attack is too high. But, unlike the 7373MAX, the KC-46 uses a similar system because the weight and balance of the tanker shifts as it redistributes and offloads fuel.

The KC-46 has a two-sensor MCAS system, which “compares the two readings,” the Air Force said.

Moreover, while the MAX 8 MCAS will reset and come back on automatically, the KC-46’s system is “disengaged if the pilot makes a stick input,” according to the Air Force. “The KC-46 has protections that ensure pilot manual inputs have override priority.”

The service declined to comment on whether the KC-46 MCAS system was in any way shaped by the MAX 8 program.

To date, the Air Force has observed “no unexpected activations of the stall prevention system” on the KC-46 during testing, “or situations similar to what is known about the two MAX 8 crashes.”

USAF’s training review is not focused on specific problems, but represents due diligence as aircraft safety questions arise in the mishaps’ aftermath, the service noted.

Two Boeing 737 MAX 8 crashes—a Lion Air flight in Indonesia last October and an Ethiopian Airlines crash near Addis Ababa earlier in March—led global airline authorities to ground the aircraft.

DEBRIS CAUSES 2ND KC-46 ACCEPTANCE PAUSE

The Air Force again stopped accepting next generation KC-46A tankers from Boeing in April after more debris was found hidden in closed compartments.

The Air Force initially stopped accepting the new tankers from Feb. 28 to March 11 after finding trash and tools in several aircraft. Officials enacted a 13-part corrective action plan to keep FOD off of the production line, but more debris was found after the action plan was implemented, causing the service to once again pause acceptance on March 23.

“The issues are unrelated to design or engineering specifications,” Air Force spokeswoman Ann Stefanek told Air Force Magazine in early April. “Air Force leadership is meeting with Boeing to approve additional corrective action plans before aircraft acceptance can resume.” She did not answer how many aircraft had debris.

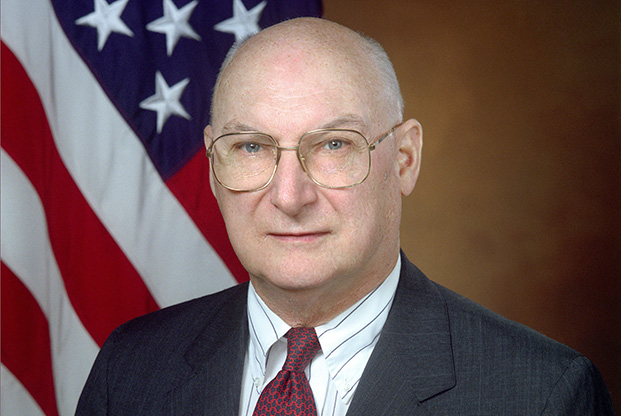

Gen. John Hyten, now head of US Strategic Command, was selected to be the next Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Photo: USAF

SENIOR OFFICER MOVEMENTS

US Strategic Command chief Gen. John E. Hyten was nominated to become the next vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the second Air Force general in a row to hold the position. His nomination was submitted to the Senate April 8.

Hyten, a leading voice in the Pentagon’s space enterprise overhaul and for nuclear weapons modernization, stepped into the top STRATCOM job in November 2016. He also brings to the Joint Chiefs a background in space operations and procurement, as the former commander and vice commander of Air Force Space Command, as well as a former space acquisition official at Air Force headquarters.

Last year, Hyten took over responsibility for building requirements for a new nuclear command, control, and communications portfolio and serves as the Defense Department’s top official overseeing the NC3 enterprise.

Army Gen. Richard D. Clarke assumed command of US Special Operations Command during a March 29 ceremony in Florida, one day after Marine Corps Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr. took command of US Central Command.

Both Clarke and McKenzie received their fourth stars before assuming command. Clarke, who previously served as the director for strategic plans and policy for the Joint Staff, replaced Army Gen. Raymond A. Thomas III, who has led the command since 2016 and is retiring. McKenzie assumed command from Army Gen. Joseph L. Votel, who also is retiring. He previously served as director of the Joint Staff at the Pentagon.

In addition, President Donald J. Trump nominated several USAF officers for new positions, pending Senate confirmation.

Gen. John Raymond (right), with USAF Chief of Staff Gen. David Goldfein (left), in 2016 became the head of Air Force Space Command. He is now nominated to become head of US Space Command, a new combatant command. Photo: Craig Denton/USAF

Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond was nominated to be the first commander of the new US Space Command. If confirmed, he will be dual-hatted, and continue to serve as commander of Air Force Space Command.

Elevating him to lead the new combatant command will give him a broader perspective and authorities as the Defense operations.

Lawmakers will consider Raymond’s nomination as they also debate the whole scope of the Defense Department’s space enterprise overhaul, which includes a Space Development Agency and a potential Space Force as a separate service under the Department of the Air Force.

Trump also has nominated Gen. Tod D. Wolters to be the next commander of US European Command and NATO Supreme Allied Commander, Europe. If confirmed, he would replace US Army Gen. Curtis M. Scaparrotti, who has led the command since replacing USAF Gen. Philip M. Breedlove in 2016. Wolters has commanded US Air Forces in Europe-Air Forces Africa since August 2016.

Lt. Gen. Jeffrey L. Harrigian was nominated for a fourth star and tapped to replace Wolters at USAFE. Harrigian has served as the deputy commander of USAFE-AFAFRICA since September 2018.

—Rachel S. Cohen

STRATEGIST AND MENTOR UNDER SEVEN PRESIDENTS

ANDREW MARSHALL: 1921-2019

Andrew Marshall Photo: Scott Davis/Army

By John A. Tirpak

Andrew Marshall, the Pentagon’s top strategist through eight presidential administrations, died March 25, at age 97.

Known to many as “Yoda,” Marshall was, from 1973-2015, director of the Office of Net Assessment; an organization charged with long-term, deep thinking about US adversaries and the best ways to counter them.

Marshall proved prescient about a number of key strategic developments. He foresaw the Cold War bankrupting the former Soviet Union, causing its collapse, and he anticipated the rise of China as an economic and military powerhouse. He also warned against the possibility that India could become a strategic adversary in the same way as China, given its rapid industrialization and willingness to invest in education and strategic industries.

Born in Michigan, Marshall was medically disqualified from military service and worked in a Detroit aircraft factory during World War II. Afterward, he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in economics from the University of Chicago, but quit a doctoral program to work for the RAND Corp. in 1949.

There he developed a theory of nations competing as corporations do, and emphasized asymmetric strategies for attacking opponents.

He joined the National Security Council in 1972 and, at the direction of then-Defense Secretary James R. Schlesinger, created the Office of Net Assessment in 1973 under the Nixon Administration. He was retained through the next seven presidential administrations because of his apolitical insight and mentorship of strategic thinkers in all the military services. His protégés include former Defense Secretaries Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney. He is credited with coining the term “Revolution in Military Affairs,” adopted by nations worldwide as shorthand for the era of networked operations, precision-guided weaponry, robotics, and information warfare.

While his emphasis on strategic competition caused Marshall to downplay or miss the threat posed by terrorism and cyber warfare, his thinking formed the basis of the George W. Bush Administration’s restructure of the US military into a lighter and more agile force.

Robert O. Work, Deputy Defense Secretary in both the Obama and Trump Administrations, said in a podcast for Defense and Aerospace Report that although he never worked in Marshall’s Office of Net Assessment, “I was really, really affected by his thinking” on strategic questions. Marshall influenced which programs Work paid special attention to as Navy undersecretary, and provided the impetus to Work’s own “Third Offset” initiative, which aimed for yet another round of leap-ahead technologies that could guarantee US technological dominance in warfare.

Air Force Gen. Paul J. Selva, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and a former military fellow under Marshall, said in the same podcast that Marshall “was all about … how to achieve strategic advantage without having to go through the messiness of tactical and operational activity; how to put your adversary in a position of strategic disadvantage” to aid deterrence and prevent the adversary from gaining the upper hand.

“That was quintessential Andy Marshall,” Selva said. “How do I get past the urgency of today? He taught me to ask that question.”

Thomas P. Ehrhard, vice president for defense strategy at the Long Term Strategy Group—another military fellow under Marshall—said in the podcast that Marshall “took a multi-dimensional, multi-perspective approach” to analyzing potential adversaries, analyses that included cultural and anthropological studies in addition to simple evaluations of hardware and military capacity.

“This was … in contrast to the systems analysis approach” favored during the Robert McNamara era, which preceded Marshall’s tenure at the Pentagon, Ehrhard said. “It was more complex than that … it was a better understanding of the whole, hence, ‘net’?” assessment. “You had to understand yourself, and your adversary, deeply.” Marshall was a “pioneer of understanding bureaucratic behavior” in the US and Soviet Union, and ‘why they behaved the way they did.”

Ehrhard also observed that Marshall’s thinking was “ruthlessly empirical. He demanded a deep, deep level of research from his people.” Selva echoed that thought, describing Marshall as “relentlessly skeptical.”

Marshall was intolerant of surface-deep analysis, Ehrhard said. “Thinking about strategy can easily become a game of words. He wanted it to be a game of information, data, logic, and evidence.” Also, it was never over for Marshall, Ehrhard noted, because the situation was always in motion, and strategies could be revised without warning. “That made a lot of people uncomfortable,” he observed.

Marshall’s infrequent reports were so closely held that their readership rarely exceeded a dozen individuals. Copies were not allowed. These reports identified “capability gaps,” or vulnerabilities that a smart adversary could exploit to neutralize US strengths, and recommended actions to close those gaps. In meetings, Marshall himself spoke little and emphasized arriving at the right questions in order to produce meaningful answers. It was left to Pentagon leaders to implement or ignore Marshall’s ideas.

His last major study, written in 2009 in concert with then-Gen. James Mattis, who later became Defense Secretary, pushed for renewal and expansion of US strategic capabilities, such as bombers, and greater realism in US wargames.

In 2012, Chinese Gen. Chen Zhou noted Marshall’s ideas as highly influential in shaping the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army. Marshall’s ideas themselves were shaped by Chinese thought, particularly those that prize winning without fighting.

“He had the ability to take hard issues apart, always looking 5-10-15 years to the horizon,” Selva said. Ehrhard called Marshall “an enigma. Painfully introverted. But that was because there was so much going on in his brain.”

James Baker took over the Office of Net Assessment in 2015, when Marshall retired, at the age of 93.

That year, Washington defense analysts Andrew Krepinevich and Andrew Watts published a book about Marshall, “The Last Warrior: Andrew Marshall and the Shaping of Modern American Defense Strategy.”

House Armed Services Committee ranking member Mac Thornberry (R-Texas) announced Marshall’s death during a hearing. Few people “have had a bigger impact on focusing our defense efforts [and] our national security, Thornberry said. “He made such a difference.”

LAST OF THE DOOLITTLE RAIDERS

DICK COLE: 1915-2019

Richard Cole Photo: SSgt. David Salanitri

By John A. Tirpak

Richard E. Cole, a key participant in the first US offensive action against Japan in WWII, and who was the last surviving member of the Doolittle Raid, died in Comfort, Texas, on April 9, at the age of 103.

Cole co-piloted the lead ship with Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle during the mission, which launched 16 B-25 Mitchell bombers with 80 men aboard from the deck of the USS Hornet on April 18, 1942 toward targets in Japan. Cole, then a 26-year old lieutenant who had joined the Army before the war, was hand-picked by Doolittle, who recruited only expert, mature aviators for the mission.

Although the raid inflicted minimal damage on Japan, and all 16 aircraft were lost either to enemy action, captured, or crashed, it was both a huge boost to American morale and a shock to the Japanese military leadership, who felt the home islands were too far away from American forces to be at any risk.

Unable to find the planned landing field in China, Doolittle’s crew bailed out of their B-25 when it ran out of fuel after 12 hours of flying. Aided by Chinese locals and western missionaries, Cole, Doolittle, and their crew evaded the Japanese and eventually made it back to the US. Of the 80 Raiders, 77 initially survived: eight were captured by Japan, and three of those were executed, while one died as a prisoner of war.

While most of the other raid survivors went to war in Europe, Cole served in Southeast Asia, flying cargo planes over the “Hump”—the Himalaya mountains—between India and China. He was later recruited to be part of the founding cadre of Air Commandos. His C-47 towed a glider of paratroops into Burma as part of an orchestrated drop of troops to launch the allied invasion of that country in 1944.

Cole attended the annual Doolittle Raider reunions, including the last, which took place in April 2013 with the last three members. He became a defacto spokesman for the group, which was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President Barack Obama in May 2014.

In later years, Cole became a kind of airpower ambassador, appearing at WWII commemorations, air shows and other aviation events, offering sharp-witted comments about the challenges of flying in WWII versus the technologies available to aviators of today.

Cole passed hours after receiving a visit from USAF Chief of Staff Gen. David Goldfein. Addressing the National Space Symposium on the day of Cole’s death, Goldfein said, “There’s another hole in our formation, and our last remaining Doolittle Raider has ‘slipped the surly bonds of Earth’ and is now reunited with his fellow raiders. And what a reunion they must be having.” Goldfein said the Air Force is “so proud to carry the torch that he and his fellow raiders handed us. …W e’re going to miss Col. Cole and we offer our eternal thanks and our condolences to his family. The legacy of the Doolittle raiders will live forever in the hearts of and minds of airmen long after we’ve all departed.”

Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson, in a statement for the press, said “the Air Force mourns” with Cole’s family. “We will honor him and the courageous Doolittle Raiders as pioneers in aviation who continue to guide our bright future.”

The Doolittle Raiders were depicted in three successful films: “30 Seconds Over Tokyo” (1944); “The Purple Heart” (1944); and “Pearl Harbor” (2001).

According to Tom Casey, president of the Doolittle Tokyo Raiders Association, there are plans for a memorial service at Randolph AFB, Texas; a burial at Arlington National Cemetery, and a ceremony at the National Museum of the US Air Force, which is the keeper of the Doolittle Raider cups. The 80 goblets are inscribed with the names of all the Raiders, and at the reunions, the goblets of those Raiders who died in the previous year were turned over. Cole’s will be the last to be turned over.

F-35AS, KC-46S TOP USAF UNFUNDED PRIORITIES LIST

The Air Force wants to buy 12 additional F-35A strike fighters and three more KC-46 tankers as part of its $2.8 billion fiscal 2020 unfunded priorities list, after requesting no aircraft in last year’s version.

On top of the Air Force’s $165.6 billion blue budget request for 2020, USAF seeks funds for readiness, cyber-hardening of space assets, aircraft procurement, and advanced technology development.

Adding a dozen more F-35As in 2020 would bring the Air Force’s total buy of Lockheed Martin Joint Strike Fighters that year to 60. Each new F-35A carries a $90.8 million price tag, so the total cost of the 12 fighters would be $1.1 billion—the same as the eight, fourth generation F-15EX jets the service wants to buy from Boeing starting next year.

Nearly $2 billion in unfunded priorities fund another 12 F-35As in 2021 and pay for spare parts. The money can also level out the KC-46 buy at 15 aircraft, the same as the service is buying in 2019 and 2021, the list notes.

The second-largest amount in the list, $579 million, would be used to boost sustainment for 10 unnamed weapons systems.

“If the Air Force does not receive supplemental and reprogramming support in FY19, we will have to take actions that drive unacceptable impacts to Air Force readiness,” USAF warned. “This [line] item would recover the lost readiness by adding necessary weapon system sustainment funding to 10 weapon systems, and includes funding for B-1 repairs and fatigue testing to address critical structural issues, as well as unanticipated B-52 and KC-135 corrosion inspections and repairs associated with an aging aircraft fleet.”

For defendable space assets, another $149 million would speed up GPS M-Code receiver development to improve the accuracy of aircraft and weapons such as the Joint Direct Attack Munition, the extended-range variant of the Joint Air-to-Surface Strike Missile, and the Small Diameter Bomb I and II.

USAF also seeks $61 million for agile development and prototyping on initiatives like directed-energy testing, navigation technology satellites, and “joint lethality in contested environments,” as well as funding support for the Air Force Warfighting Integration Capability and senior leaders’ projects.

A “high-speed, vertical lift demonstration,” named Agility Prime, needs another $25 million, the Air Force added.

Another $18 million would advance hypersonics; nuclear command, control, and communications; and artificial intelligence, machine learning, and unmanned systems.