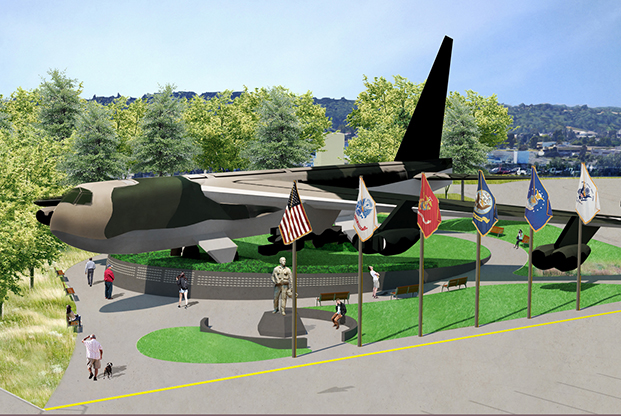

A rendering of a new Vietnam Veterans Memorial Park, set to open in Seattle on May 25, featuring the restored Midnight Express B-52G Stratofortress. The memorial is at Seattle’s Museum of Flight. Illustration: Courtesy of Project Welcome Home

When former Air Force pilot James Farmer first laid eyes on the rusting hulk of the broken-down B-52 bomber in an out-of-the-way corner of Paine Field, just north of Seattle, it was like looking upon a forgotten veteran, lying on his deathbed.

“It was heartbreaking,” Farmer said. “It was like seeing a dear old friend that was just totally deteriorating. Like a friend you hadn’t seen in 30 years and you barely recognize them because they’re in such bad shape. The paint was peeling, it was an ugly color, pieces were falling off. It was nasty.”

The B-52 had been sitting on Paine Field, a former military airport, since 1991, when it was decommissioned from the Air Force. Eventually donated to Seattle’s Museum of Flight, 40 miles away at Boeing Field, just south of Seattle, it was too big and expensive to move.

So it sat. For nearly 30 years.

Now it’s set to become the centerpiece of a new Vietnam Veterans Memorial Park, which will open in Seattle on May 25 over Memorial Day weekend.

“What we wanted to create was a place where all Vietnam veterans would feel honored and welcomed home,” Farmer said. The B-52 could be part of it. And so began what became known as “Operation Welcome Home.”

After Vietnam veteran and former Air Force pilot James Farmer discovered a decaying B-52 Stratofortress 40 miles from Seattle, he and others set out to restore the airplane and build a Vietnam War Memorial. Photo: Jon Anderson

For Farmer, the B-52 really was on old friend. Both took part in Operation Linebacker II, a bombing campaign credited with forcing North Vietnam to the peace table in early 1973 and ultimately returning hundreds of US prisoners of war from captivity.

Joe Crecca was one of those POWs. His F-4 Phantom was hit by a surface-to-air missile over North Vietnam, his jet literally blowing apart around him as he ejected.

“If I had taken just the split second to drop my helmet visor, like I was supposed to, I wouldn’t be here right now,” Crecca said. Captured as soon as he hit the ground, Crecca was taken to the infamous Hanoi Hilton, where he was beaten, tortured, and later placed in solitary confinement, where he risked tapping out a coded message to a fellow prisoner in an adjacent cell.

He smiled as he decoded the tap-tap-tap of the response in his head: “Don’t give up. Keep up the fight.” Months later, Crecca met the US Navy prisoner who encouraged him to endure: then-Lt. Cmdr. John McCain.

For the next six years, Crecca repeated that mantra—Don’t give up. Keep up the fight.

Former POW and Air Force F-4 Phantom pilot Joe Crecca survived the Hanoi Hilton and saved the old B-52 by relying on the same mantra: Don’t give up. Keep up the fight. Photo: Jon Anderson

And now for the past six years, he’s found himself saying those words again, as he, Farmer, and a core grassroots group of veterans and volunteers have struggled to find an appropriate home for the B-52 and also a welcoming place for fellow Vietnam veterans.

They raised $3 million to restore, dismantle, move, and reassemble the B-52, bring it to its new location adjacent to the Museum of Flight, and build the park itself.

“It was a massive effort,” said Tom Cathcart, the museum’s director of aircraft collections.

First, the aircraft needed the scrub down of its life, removing decades of Seattle grime and rust. The cowlings for the planes eight underwings had to be fully overhauled. Fresh paint came next, and only then was the entire aircraft—the size of a Boeing 747 jumbo jet—disassembled for its journey. The 171-foot main body was disconnected from the 135-foot-wide wing section, which was then cut in half. The 30-foot-tall tail was removed, and its vertical fin disconnected as well.

“That’s a lot of bolts—some the size of Coke bottles—that really don’t like being unbolted after that many years,” said Cathcart.

Finally, under the cover of darkness—to minimize traffic disruptions—the pieces were loaded onto a convoy of extra-long flatbed trailers for the slow, three-hour trek to the other side of Seattle.

“It was an amazing sight to see,” Farmer said, beaming as he showed off the reassembled, fully restored aircraft at its new home. “It’s like it drank from the Fountain of Youth.”

The balance of the funds raised by Operation Welcome Home are now paying for the final touches to the park that is being built around the aircraft. The park will also feature flags from each branch of the Armed Forces and an 8-foot, bronze statue of an airman in flight gear carrying a folded US flag.

“The airman symbolizes the veterans who were able to return home alive,” Farmer said. “The flag represents those who made the ultimate sacrifice.”

If you plan to visit: Seattle’s new Vietnam Veterans Memorial Park, featuring a restored B-52G Stratofortress, memorial statue, and a tribute wall with personalized plaques from people honoring the veterans in their lives, opens May 25 with an opening ceremony, including aircraft flyovers, a color guard presentation, and a special pinning ceremony honoring Vietnam veterans in attendance. Throughout the May 25-27 Memorial Day weekend, veterans will be admitted free, along with one adult and any children under 17. RSVPs are requested but not required.

–––

Jon R. Anderson spent more than 25 years as a military affairs reporter with Military Times and Stars and Stripes. He is now an independent writer based in the Pacific Northwest.