Sunrise over Earth. Photo: Arek Socha/Quimono

The increasing military importance of space permeated the 34th Space Symposium in April. Speakers from Vice President Michael R. Pence down through a range of military and Air Force officials underscoring the need to focus on space as a warfighting domain, as the Trump administration has declared it to be.

The emphasis on the national security space enterprise has been an increasing focus in Washington in recent months. It has been prominent in, for example, the administration’s December National Security Strategy and in continuing calls from some in Congress for establishment of a space force or space corps as a military service separate from the Air Force.

Pence’s remarks, at the start of the event went far beyond the national security aspects of space. He did, however, describe the newly re-established National Space Council’s proposal to shift basic space situational awareness to the Commerce Department as a step being taken “so that our military leaders can focus on protecting and defending our national security assets in space.”

Moreover, he pointed to Trump’s statements that “space is a warfighting domain, just like the land, air, and sea” and calls for the Pentagon to strengthen the resilience of US space systems in the face of Russian and Chinese pursuit of anti-satellite capabilities.

It was Defense Department officials at the conference, though, who really hammered the point home. In speeches and remarks to reporters, DOD leaders reminded listeners of the National Security Strategy declaration that the US “considers unfettered access to and freedom to operate in space to be a vital interest.” Similarly, they emphasized how the National Defense Strategy designated space as a warfighting domain.

Gen. John W. Raymond, commander of Air Force Space Command headquartered at Peterson Air Force Base and the Joint Force Space Component under US Strategic Command, pointedly predicted that future historians will look back on 2017 and 2018 as “one of the most critical times in our national security space history.”

It will be seen, he suggested, “as a strategic inflection point for national security space and a bold shift toward warfighting and space superiority.”

The sense of being at a critical juncture—a key moment in the history of the US national security space enterprise—was a common thread throughout the presentations that Raymond and his colleagues made during the symposium. Also high on the agenda was the recurring theme that the defense and security elements of the US government are increasingly focused on dealing with national security issues raised by the changing space environment.

_Read this story in our digital issue:

Gen. John E. Hyten, commander of US Strategic Command and former commander of Air Force Space Command, told reporters there was “no doubt in my mind we’re going to have to deploy defensive counterspace systems because our adversaries are building offensive counterspace systems.”

“The nation’s going to have to make a decision on what we do in order to challenge somebody else’s space capabilities. I think we’re going to go down that path. I think we have to go down that path,” Hyten said.

He said understanding of the threat in space has grown in Washington policy circles in recent years.

“I think five years ago there was very little understanding,” Hyten said. “Today, there’s a broad understanding that continues to expand.”

He praised the House Armed Services Committee’s Strategic Forces Subcommittee for defining in legislation—including the National Defense Authorization Act—what needs to be done in space.

“They talked about the threat exactly right. They talked about the need to respond to that threat exactly right,” Hyten said.

There were “significant discussions” in the press and publicly about space as a warfighting domain or the idea of a space corps or force, he said.

“But the real benefit, the real strength of that law was the identification of the problem. That will allow us now to engage with the broader members of Congress to further educate them on what the threat is. And we’ve also shared a very detailed tabletop exercise with the members of the Senate and House Armed Services committees so they can see the full implication of all the things that we’re worried about,” he said.

“We’re still on the education path,” Hyten said, “but it’s far more mature than it was just five years ago.”

As a consequence, the administration has increasingly focused on national security space, speakers said, with Raymond telling reporters it is clear “our nation’s senior leaders are laser-focused on the space domain.”

He pointed to a number of steps already taken, including the administration’s 2019 budget request that includes almost $7 billion more for space, growing partnerships with the National Reconnaissance Office and with industry, establishment of a four-star Space Component Command in US Strategic Command, and the planned conversion of the Joint Space Operations Center into a Combined Space Operations Center.

However, even as the government has already taken steps to focus more on national security space, “it is time to go further,” Air Force Secretary Heather A. Wilson said, and she announced a series of steps at the symposium to do just that.

SBIRS-4 is ready for encapsulation in January 2018 at Cape Canaveral AFS, Fla. The SBIRS payloads are classified. Photo: Jim Dowdall/Lockheed Martin

INTERNATIONAL SPACE

Addressing a dinner audience, Wilson said now is the time to expand national security space relations with allies and partners because the US faces “a more competitive and dangerous international security environment than we have seen in decades.”

As America’s great power rivals, “Russia and China are developing capabilities to disable our satellites,” she added.

She announced the Air Force would, starting next year, increase the availability of Air Force space training for allies and partners by adding two more courses to the National Security Space Institute, including one on space situational awareness. USAF would also open more of the existing advanced national security space courses to members of allied nation militaries, including those of France, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, and possibly others—Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom were already in. “Countries with allies thrive and those without allies” do not, she told reporters before her speech.

“We will strengthen our alliances and attract new partners,” Wilson said, “Not just by sharing data from monitoring, but by training and working closely with each other in space operations.”

She said an increasing number of countries are establishing space interests or launching satellites, adding, “there are more countries that are allies of ours that we probably want to train together.”

“One of the key lines of effort in the National Defense Strategy is to deepen our alliances and partnerships. This is just one of the ways we’re going to be doing this in the space domain,” she said.

Raymond also pointed to the importance of international partnerships.

“We’re increasing our training with an international coalition of allies and partners,” he said, for example, having added France, Germany, and now Japan to the Air Force Space Command Schriever Wargame series.

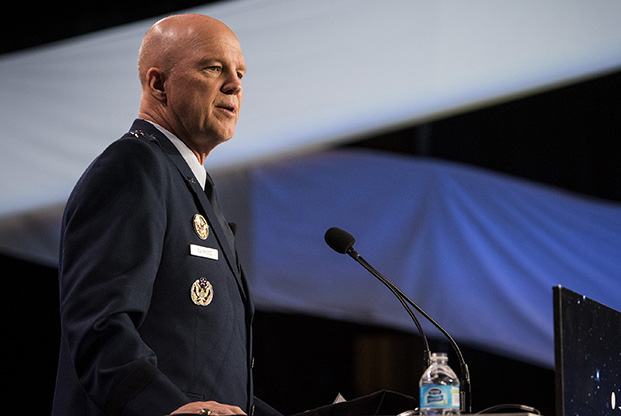

Gen. John Raymond, head of Air Force Space Command, speaks at the 34th Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, Colo., in April. Photo: David Grim/USAF

One reason alliances are important is because not all responses to space threats will necessarily be in the space domain itself.

The National Security Strategy includes a statement, which Raymond pointed to in his speech, that any harmful interference with, or attack on, critical components of the US space architecture that directly affects unfettered US access to, and freedom to operate in, space will be met with a deliberate response “at a time, place, manner, and domain of our choosing.”

Hyten returned to that phrase during his press conference to talk about the likely US response to a space attack.

The reference to the US responding in a domain of its choosing, Hyten said, “is a huge change in our overall strategy.”

The passage, he said, focuses on something STRATCOM has been looking at for a while, which is how to fight a war that goes into space.

“My answer is, the first thing I’m going to do is I’m going to call the geographic combatant commander that’s actually fighting whoever the opponent is on the Earth and find out what the heck is going on in that world. And, oh, by the way, the response that we work out to recommend if warfare does extend into space may not be in space. It may be in cyberspace, it may be in the air, it may be some other place,” he said.

“What I don’t want,” he said, is “war to effectively go kinetic and big in space because that is where the United States loses,” because the kinetic effects created in space last a long time, and the nation with more space capability has more to lose because of the danger to space assets from debris.

So, the addition of language referring to a domain chosen by the US opens new possibilities, he said.

“No. 1, when we train and exercise, instead of just going ‘Okay, now you have a space problem. STRATCOM, what are you going to do?’ It’s ‘what domain are you going to respond to?’ And we have to now develop broad-based plans, broad-based structures, then we have to figure out how to exercise those broad-based plans across multiple combatant commands. That’s going to drive multicommand exercises that we really have to do. You talk about space, it’s always a global problem.”

That means that “if we’re doing something in the Pacific, European Command actually has to play, because everything we do impacts the entire world,” Hyten said.

The point, he told reporters, is that the US will respond to actions in space by its adversaries “as part of the broader conflict.” Therefore, “you have to look at war from the perspective of the adversary and you, not from domain to domain.”

Adversaries must know the US response “can be significant, and it will be something that would hurt them, [and] that’s why they should not ever want to go down that path,” said Hyten.

Gen. John Hyten, commander of US Strategic Command, moderates a panel on “Recapturing Our Ability to Go Fast” at the symposium. Photo: David Grim/USAF

HURRY UP DON’T WAIT

The US still has serious vulnerabilities in space it must address, but schedules can be slow and ponderous. The Air Force is working to address this as well.

Wilson said US satellites are to become more resilient and defendable and must be developed more quickly. She said the time for replacing the canceled seventh and eighth Space-Based Infrared System missile warning satellites would be cut from nine to five years for the new satellites.

As part of moves to speed up acquisition, Wilson said USAF would set up an office reporting to the assistant Air Force secretary for acquisition, whose job “is not to buy things, but to change the Pentagon rules on how we buy things so that speed is possible.”

“I’m not sure what we’re going to call it. Perhaps AQ Delta—the fourth letter in the Greek alphabet—which in mathematics is the symbol for change. Or perhaps we’ll find a name slightly less geeky and obscure,” she said.

Finally, she said, Los Angeles Air Force Base’s Space and Missile Systems Center—in charge of space systems procurement—would be revamped to eliminate stovepipes and to streamline its operations.

Altogether, the Air Force is working to make its space capabilities more flexible so it can respond faster, winning wars in ways enemies can’t predict. “It’s not space for space’s sake,” Hyten noted, because “there’s no such thing as war in space, there’s just war.”