The Air Force’s first African American Airmen helped win World War II, then helped integrate the Armed Forces.

The Tuskegee Airmen are best known as the first African American pilots in United States military service. Flying P-39, P-40, P-47, and P-51 fighters, they refuted any notion that Black men lacked the ability to fly advanced aircraft successfully in combat, Indeed, their excellent performance in World War II contributed to the racial integration of the armed services in 1948. From their ranks came the Air Force’s first three African American generals.

Other African American pilots preceded the Tuskegee Airmen, but they were either civilians or served in foreign air forces. Eugene J. Bullard, the first African American military pilot, served in the French Air Service during World War I, for example, and John C. Robinson later served in the Ethiopian armed forces in the 1930s.

Of the 992 Tuskegee Airmen pilots who completed advanced flight training at Tuskegee Army Air Forces, eight were still alive a year ago. Now nearly a century old, their ranks are dwindling rapidly. Four died in 2022—Charles McGee, Alexander Jefferson, William Rice, and Christopher Newman—and one more, Harold H. Brown, died in January 2023. At this writing, just three of those who flew red-tailed P-51 Mustangs survive: Charles W. Cooper, George E. Hardy, and Harry T. Stewart Jr.

The U.S. Army acquired its first military airplane in 1909, and for the next 30 years, Blacks were not allowed to fly. An Army War College report issued in 1925 reflected the Army’s attitude at the time: It claimed Blacks were inferior and should be restricted to subordinate positions. To be a pilot was to be an officer, and the Army of the time did not want Black officers commanding White enlisted men. The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps maintained the same position. In fact, neither the Navy nor the Marine Corps had a single Black pilot until after World War II.

The breakthrough came during President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1940 re-election campaign, in which he sought an unprecedented third term. Roosevelt promised to let African Americans train to be pilots in the U.S. Army Air Corps. After winning the election that November, Roosevelt’s War Department announced in January that the Army would train Black pilots at Tuskegee, Ala. In March, the 99th Pursuit Squadron (later renamed the 99th Fighter Squadron) was established as the United States Army Air Corps’ first Black flying unit. The squadron had no qualified pilots yet, but it would soon. They would become known as the Tuskegee Airmen.

Tuskegee was chosen for a number of reasons. Its climate allowed more days of good flying weather than airfields farther north, and the Tuskegee Institute had already trained Black civilian pilots there. Its leaders lobbied for the military pilots to be trained there, as well. The War Department wanted to keep flying units segregated, and in Alabama, racial segregation was the norm. Instead of training at bases all over the country, as White pilots did, the African American pilots would complete primary, basic, and advanced flight training only at Tuskegee. Nearly 1,000 African American men completed that course.

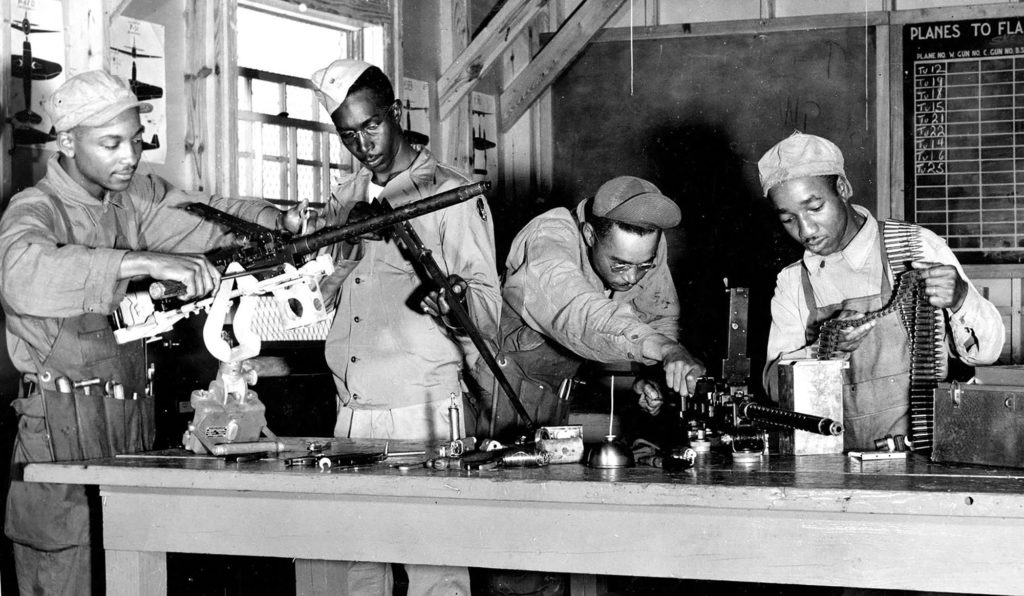

The term Tuskegee Airmen refers today not only to the military pilots who trained at Tuskegee, but also thousands of ground personnel who served in those same units, such that in the end there were well over 14,000 Tuskegee Airmen in all. Yet only a small fraction of the tens of thousands of African Americans who served in the Army Air Forces during World War II were Tuskegee Airmen. There were also some White Tuskegee Airmen; the first commanders of the Tuskegee Airmen units were White, as were the majority of the flight instructors at Tuskegee Army Air Field. However, the overwhelming majority of Tuskegee Airmen were Black.

Flight training at Tuskegee took place in three phases. The first phase, primary flight training, took place at Moton Field, owned by the Tuskegee Institute, and operated under contract with the Army Air Forces. Primary flight training took place in PT-13 and PT-17 biplanes and PT-19 monoplanes, just like primary flight training for White aviators in other parts of the country. Almost all the flight instructors in the primary phase of flight training at Moton Field were Black. Some of them had trained civilian pilots at Tuskegee Institute before America’s entry into World War II. The most famous among them was Charles Anderson, called “Chief” Anderson because he was the chief pilot instructor for Tuskegee Institute. Chief Anderson had taken Eleanor Roosevelt, the President’s wife, on a flight over Tuskegee during civilian flight training there, just after the War Department constituted and activated the 99th Pursuit Squadron at Chanute Field, Ill., which later was renamed the 99th Fighter Squadron and relocated to Tuskegee, where it was assigned its first pilots.

It took nine to 10 weeks to graduate cadets from primary flight training at Moton Field. Then they went on to train at the much larger, Army-owned Tuskegee Army Air Field several miles to the northwest. Basic flight training, which began with the BT-13 monoplane, lasted another nine to 10 weeks and was followed by advanced flight training, still another nine to 10 weeks, in AT-6 traubes for future fighter pilots, and AT-10 twin-engine aircraft for future medium bomber pilots. Eventually, advanced fighter pilot students flew P-40 aircraft at Tuskegee Army Air Field, and advanced bomber students flew B-25s.

The commander of Tuskegee Army Air Field during most of World War II was Col. Noel F. Parrish, a White officer from the South who, unlike his immediate predecessor, integrated the base facilities. Tuskegee Airmen pilots remembered Parrish as a fair man who was genuinely interested in their success. He enforced strict flying training standards, such that only about half the cadets who entered flight training completed it. But those who did were fully qualified for the combat missions that lay ahead of them. Many who “washed out” became B-25 bomber crewmen.

A total of 44 classes of pilots graduated from advanced flight training at Tuskegee Army Air Field. Colonel Parrish became an early advocate of a racially integrated Air Force.

After graduation, the new pilots were assigned to military units including the 99th Fighter Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group and its three fighter squadrons, the 100th, 301st, and 302nd. All of those units served at Tuskegee Army Air Field until the spring of 1943, when the 99th deployed overseas and the 332nd Fighter Group moved to Selfridge Field, Mich., for further transition training, before eventually deploying overseas in early 1944. Replacement pilots for the 332nd Fighter Group, after it deployed overseas, were trained at Selfridge and later at Walterboro, S.C.

Future bomber pilots went to the 477th Bombardment Group and its four bombardment squadrons: the 616th, 617th, 618th, and 619th, which was activated at Selfridge when the 332nd Fighter Group vacated the base. Col. Robert Selway, a White officer who earlier had commanded the 332nd Fighter Group, took command of the 477th. By the time the Tuskegee Airmen organizations went overseas, they were all Black.

Yet the most important commander of the 99th Fighter Squadron was a Black officer, Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr., a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point who was also in the first class of Black military pilots to train at Tuskegee. Davis took the 99th overseas in the spring of 1943 and eventually also became commander of the 332nd Fighter Group, just before it deployed overseas. The son of the first Black general in the U.S. Army, Davis went on to become the first Black general in the U.S. Air Force, following World War II.

The 99th Fighter Squadron was not originally assigned to the 332nd Fighter Group. After it left Tuskegee Army Air Field in the spring of 1943, it voyaged first to North Africa, where it was attached to various White fighter groups, since there was not yet a Black fighter group overseas to which it could be assigned. It flew P-40 fighters for the 12th Air Force, to support surface forces such as Allied shipping in the Mediterranean Sea. It also flew strafing missions against enemy-held islands such as Pantelleria and Sicily, in concert with the White fighter squadrons, which also flew P-40s. During their first six months operating overseas, the Tuskegee Airmen shot down only one enemy airplane. That was understandable, given its mission was mainly to support surface forces and to destroy enemy targets on the ground. The first African American pilot to shoot down an enemy airplane was 1st Lt. Charles B. Hall, on July 2, 1943. It would be six months before there was another. Lack of opportunity, rather than lack of skill, was the reason.

Bias was also at play. Col. William W. Momyer, commander of the mostly White 33rd Fighter Group, to which the 99th Fighter Squadron was attached, tried to take the Tuskegee Airmen out of combat, claiming the 99th performed poorly in comparison to his group’s White squadrons. His recommendation was forwarded up the chain of command, with endorsements, all the way to the head of the Army Air Forces, Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold. But when the War Department launched a study comparing the 99th Fighter Squadron, under Colonel Davis, with the other P-40 units in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, it concluded that the pilots of the 99th Fighter Squadron few just as well as their White counterparts, and found no justification to remove the unit from front-line combat. Indeed, in January 1944, the 99th Fighter Squadron outperformed some of the White fighter squadrons over Anzio, shooting down more enemy aircraft in a two-day period.

When the 332nd Fighter Group and its three fighter squadrons, the 100th, 301st, and 302nd, finally deployed from Selfridge Field to Italy, in early 1944, it was flying P-39 aircraft. Like the 99th Fighter Squadron which was already in Italy flying P-40s, the 332nd Fighter Group flew missions for the 12th Air Force, supporting ground forces. Designed to destroy targets on the ground, its P-39s weren’t suited for air-to-air combat.

In the summer of 1944, the 99th Fighter Squadron was reassigned to the 332nd Fighter Group, making it the only fighter group in World War II combat with four, rather than three squadrons. That same summer, the 332nd was reassigned o the 15th Air Force, which also flew four-engine B-17 and B-24 heavy bombers. Their new mission: Escort those bombers to and from their targets, to protect them against enemy airplanes. For the new mission, the 332nd Fighter Group traded its P-39s for P-47s, and eventually P-51 Mustangs, which were faster, more maneuverable, and offered longer range than the earlier models. Now able to fly combat missions deep into enemy territory, the opportunity to square off against enemy airplanes and shoot them down increased. In the middle of 1944, the 332nd Fighter Group moved to Ramitelli Airfield in Italy to fly its bomber escort missions. It would also continue to fly some strafing missions.

The 15th Air Force had 21 bombardment groups, each with four bombardment squadrons. But it had just seven fighter groups to escort those bombers, four of them flying P-51s, and three flying P-38s. All four of the P-51 Mustang groups, including that of the 332nd Fighter Group, had distinctively painted tails. The 332nd Fighter Group’s P-51 tails were solid red. The 52nd Fighter Group’s tails were yellow, the 31st Fighter Group striped red, and the 325th Fighter Group were black and yellow checkerboards. The distinctively painted tails helped fighter and bomber crews identify friend from foe.

These were the missions for which the Tuskegee Airmen became famous. Of the 312 missions they flew for the 15th Air Force, 179 of them were bomber escort missions. Most were highly successful. In fact, the Tuskegee Airmen would lose escorted bombers to enemy fighter pilots on just seven of those missions, losing a total of 27 bombers in those missions. By contrast, the average number of bombers lost to enemy fighters by each of the other 15th Air Force fighter escort groups was 46 during the same period The Tuskegee Airmen lost significantly fewer escorted bombers to enemy aircraft, on average than the other groups over the same period.

Enemy anti-aircraft artillery proved more dangerous to bombers than rival fighters, but the fighter escorts could do nothing to protect the bombers against flak.

At the end of December 1944, bad winter weather forced 18 B-24 bombers of the 15th Air Force to land at Ramitelli, home base of the Tuskegee Airmen. The 332nd Fighter Group welcomed some 180 White bomber crewmen, sharing their shelters, equipment, and supplies for most of a week. During those few days, the Black and White Airmen interacted cordially, and after, many of the White bomber crews remembered with gratitude the hospitality they were shown. Most of the White bomber crews had never before met the Black fighter pilots who sometimes escorted them, and afterward, some bomber crews requested the red-tailed P-51s of the 332nd Fighter Group be their escorts.

It is very possible that one reason the 332nd Fighter Group lost fewer bombers to enemy airplanes than the other escort groups is that its pilots were ordered not to leave the bombers to go chasing after enemy fighters; that would have left the bombers more vulnerable to attack. There is some evidence to support this thesis. While the other fighter groups lost more bombers, they also each shot down significantly more enemy fighters in comparison to the Tuskegee Airmen. It could be that the other groups shot down more enemy airplanes because they were more willing to leave the bombers to chase enemy fighters that posed only an indirect threat.

On March 24, 1945, the 15th Air Force flew its longest mission of the war. Germany’s capital, Berlin, was normally a target for the 8th Air Force, based in England. But for this mission, five of the seven fighter groups, including the Tuskegee Airmen of the 332nd Fighter Group, flew to Berlin. Two of the groups, the 31st and the 332nd, shot down German Me-262 jets, including three by the 100th Fighter Squadron. It was the first time the Black pilots had shot down German jets, but the victories came at a cost: three of their escorted bombers were shot down by enemy airplanes.

The 332nd Fighter Group flew many strafing missions for the 15th Air Force between early June 1944 and the end of April 1945. On one memorable mission, on June 25, 1944, eight of the Tuskegee Airmen pilots strafed a German warship and claimed to have sunk it. The only German warship attacked at the same time and place was the TA-22, the former Italian destroyer Giuseppe Missouri. Naval records show that the TA-22 did not sink that day, but was decommissioned later, and then scuttled in 1945. While they may not have destroyed the ship that day, the Tuskegee Airmen did enough damage to put it out of action. Other strafing missions destroyed German rail traffic and other ground targets.

By the end of the war in Europe, 72 Tuskegee Airmen pilots had shot down 112 enemy airplanes. That includes the 99th Fighter Squadron before it joined the 332nd Fighter Group, and missions of the squadron and the other squadrons of the 332nd Fighter Group for both the 12th and 15th Air Forces. No Tuskegee Airmen shot down the five enemy airplanes to be labeled an ace, but three of the Black pilots came close, shooting down four enemy airplanes. Four others shot down three enemy airplanes in a single day. Together, they also destroyed numerous enemy airplanes on the ground during strafing missions.

Of the approximately 1,000 Tuskegee Airmen pilots, 355 deployed overseas and engaged in combat operations. More than 100 Tuskegee Airmen were reported lost on missions, though many eventually made it home. Scores of 332nd Fighter Group fighter pilots did not return, however, but were killed by enemy fire, either from rival aircraft, flak, mechanical failure, or accidents.

Thirty-two Tuskegee Airmen became prisoners of war in Germany. Two of them, Alexander Jefferson and Harold Brown, wrote books about their experiences. They were placed in racially integrated camps where the prisoners were segregated not by race but by rank, the officers in one place and the enlisted personnel in another. Ironically, the Tuskegee Airmen POWs found themselves in a more racially integrated environment in their camps in Nazi Germany than they had been in parts of the United States.

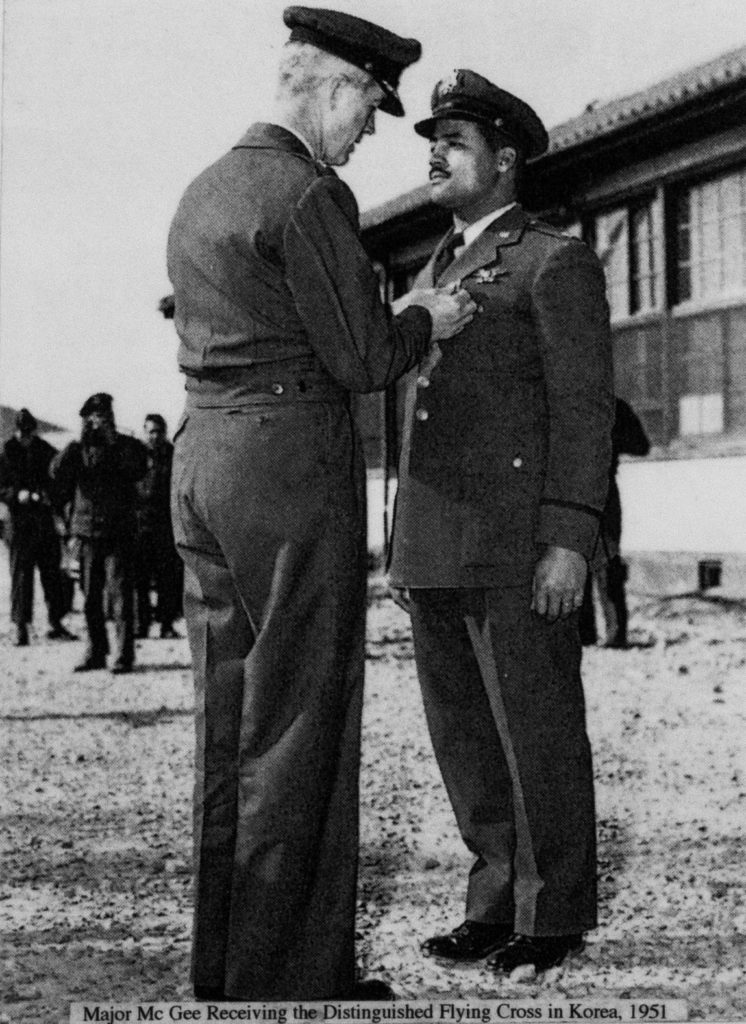

Their success could not be ignored. By the end of the war in Europe, 95 Tuskegee Airmen earned a total of 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses (one earned an oak leaf cluster, by getting the award twice). The 99th Fighter Squadron earned three Distinguished Unit Citations, two of them while flying with White fighters, and one while flying with the 332nd. The group and its other three squadrons earned a Distinguished Unit Citation for the Berlin mission.

Multi-engine bomber pilots who trained at Tuskegee served in the 477th Bombardment Group and its four squadrons, the 616th, 617th, 618th, and 619th. That group never deployed overseas or took part in combat, but its story is important in the history of civil rights. At Selfridge Field, Mich., and later at Godman Field, Ky., and Freeman Field, Ind., its personnel struggled against segregated base facilities. In April 1945, at Freeman Field, some 120 Black officers were arrested, in two waves, for attempting to integrate a White officers club, or for refusing to sign a base regulation demanding segregated facilities on base. Some of the 61 arrested in the first wave were arrested also in the second wave of 101. Eventually, all but three of those arrested were released, but only after receiving written reprimands. The controversy attracted national attention. Two of the arrested Tuskegee Airmen were found not guilty at court-martial, and only one, Roger Terry, was convicted. He was fined and given a dishonorable discharge.

The War Department ultimately solved the integration problem by making the 477th Bombardment Group all-Black and assigning its White “trainer” officers to other units. Replacing Col. Robert Selway as group and base commander was Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr., who arrived in June 1945, after the war in Europe had ended. Davis, who had commanded the 99th Fighter Squadron and then the 332nd Fighter Group in combat overseas, became the first Black commander of an Army Air Forces base. Just after the war, the 477th Bombardment Group, renamed the 477th Composite Group, moved to Lockbourne Air Force Base, Ohio.

In 1947, the same year the U.S. Air Force was established as a separate military service, the 477th was inactivated, and the 332nd Fighter Group, which had been inactivated at the end of World War II, was re-activated at Lockbourne. The group was assigned to a newly established and activated 332nd Fighter Wing, also at Lockbourne, under Davis’ command.

Air Force Magazine and the 1949 USAF Gunnery Meet

The four winning Tuskegee Airmen from the 332nd Fighter Group—(from left) Lt. Halbert Alexander, Lt. James Harvey, Capt. Alva Temple, and Lt. Harry Stewart—pose with their “Top Gun” trophy during the awards ceremony for the First Aerial Gunnery Competition at Las Vegas Air Force Base, Nev., (now Nellis AFB) in 1949.

The Air Force’s first gunnery meet pitted “12 three-man teams representing virtually every fighter group in the country” in a shootout in the Nevada desert “for top honors in five fields.” So reported Air Force Magazine in its June 1949 edition.

“The competition was spirited—no one held anything back,” the magazine reported. “Scores were good when compared to wartime scores (about 100 percent better in fact), but somewhat disappointing in that the meet averages failed to come up to intra-group scores.” Jets were still new in 1949, and the competition featured both jets and “conventional fighters.” They competed in “all types of fighter offensive techniques,” including “skip bombing, dive bombing, strafing, rocketry, and aerial gunnery.”

The article identified the winning team in both the jet class and the conventional class, and displayed photographs of both teams: The 4th Fighter Group, an all-White unit flying F-80s, won the jet category, its team including Capt. Vermont Garrison, 1st Lt. James Roberts, and 1st Lt. Calvin Ellis. The 332nd Fighter Group, an all-Black unit flying F-47s, was victorious in the conventional category, its team comprised of Capt. Alva Temple, 1st Lt. Harry Stewart, and 1st Lt. James Harvey.

Both groups were recognized in the awards ceremony. There was no overall winner, since there were five events in the propeller aircraft class, and only four events in the jet aircraft class.

The trophy commemorating these events disappeared over time, eventually coming into the hands of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and later the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio. It was discovered in the archives in the early 2000s, and in a 2022 interview with CBS News, Harvey related that a museum staffer had allegedly asserted “this item will never be on display.”

The trophy is on display now, including a small brass plaque on its base identifying all the winners of the 1949 and 1950 competition, including the three Tuskegee Airmen who won the conventional class in 1949. The plaque must have been engraved after the 1950 event, as it identifies several of the 1949 winners (both White and Black) at higher ranks than when the 1949 event took place.

In 1991, Air Force Magazine’s then-editor, John Correll, added a section to the magazine’s annual Almanac under the heading “Records, Trophies, and Competitions.” But in its listings of winners of the “Gunsmoke” competitions, it listed the winners of the 1949, 1950, and 1954 events—no gunnery competition was held in either 1952 and 1953—as “unknown.” The 1992 edition identified only the “4 FIW” as the 1949 winner, leaving out mention of the 332nd Fighter Group; not until 1995 were all the winners listed. Then, from 1998 on, the magazine stopped listing the early winners, instead only identifying winners from 1981 onward, the date at which the “Gunsmoke” name became the official title of the competition.

Over the years, questions have arisen over whether that omission was intentional. It is impossible to know for sure what drove these decisions, but the evidence suggests otherwise. Leaving out the 332nd Fighter Group, while including the 4th Fighter Group, in three annual almanac issues (1992, 1993, 1994) did obscure the achievement of the all-Black 332nd Fighter Group. But the same could be said of leaving out the all-White 27th Fighter Escort Group in listings for 1950’s winners, in the 1994, 1995, 1996, and 1997 editions. That suggests that the omission of the 332nd Fighter Group from 1992 to 1994 was not racially motivated.

—Daniel Haulman and Tobias Naegele

WINNERS IN VEGAS

In 1949, the Air Force held its first gunnery meet in Las Vegas, Nev. The 332nd Fighter Group won the propeller-aircraft category and the 4th Fighter Group won the jet aircraft category. This proved the last hurrah of the 332nd Fighter Group, because later that same year, the group, its like-numbered wing, and its squadrons were all inactivated. President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981 in 1948, integrating all the armed forces. Instead of assigning White personnel to the Tuskegee Airmen units, Black members of those units were reassigned to formerly all-White units. Every all-Black flying unit was inactivated. Segregated training had already been phased out. The Air Force began training Black and White pilots together at Williams Air Force Base, Ariz., after the closure of Tuskegee Army Air Field in 1946.

The Tuskegee Airmen experience lasted from 1941, when the first Black flying unit was constituted and activated, until the middle of 1949, when the last all-Black flying units were inactivated at Lockbourne Air Force Base. Many of the Tuskegee Airmen elected to remain in the Air Force after 1949, some of them flying combat missions in Korea and Vietnam. Among them were Col. Charles McGee, who died last year at age 102, having been promoted to the honorary rank of brigadier general in 2020. McGee flew 409 fighter combat missions in three wars. Lt. Col. George Hardy flew in the same three wars, flying fighters in World War II, bombers in Korea, and gunships in Vietnam. The future Gen. Daniel “Chappie” James, who served with the 477th Bombardment Group (477th Composite Group) during World War II, likewise served in combat in Korea and Vietnam, eventually becoming the Air Force’s first Black four-star general. The first three Black generals in the United States Air Force were all Tuskegee Airmen.

Other Tuskegee Airmen went on to play key roles in the civil rights movement, in politics, and other fields of endeavor. Among them was the first Black mayor of Detroit, Coleman Young. In terms of civil rights and the integration of the United States armed forces, the Tuskegee Airmen played a revolutionary role. The integration of the American military was the first step in the integration of American society.

It was never easy. The Tuskegee Airmen encountered obstacles and endured humiliating racial injustices, but their story is not just what White men did to try to hold back Black men. It is also the story of what Black men and White men did for each other—and what they did together—against a common enemy. There is no telling how many 10-man heavy B-17 and B-24 bomber crews owed their lives to the Black pilots who escorted them through enemy fighter attacks, and there is no doubt those Black pilots received most of their basic and advanced flight training from White flight instructors at Tuskegee Army Air Field.

We should remember the Tuskegee Airmen story as a Black and White story, a story of American military personnel who served their country and furthered the great principle that all men are created equal, established at its founding. The ideal had not yet been achieved by 1949, but the Tuskegee Airmen took great strides toward it then. Their achievements should never be forgotten.

Daniel L. Haulman, former head of the organizational histories branch of the Air Force Historical Research Agency, is the author of several books on the Tuskegee Airmen, including “The Tuskegee Airmen, an Illustrated History” (with Jerome Ennels and Joseph Caver), “The Tuskegee Airmen Chronology,” and “Eleven Myths About the Tuskegee Airmen.” His next book, “Misconceptions about the Tuskegee Airmen,” is due to be published in February.