The 1948 Key West Agreement established the roles and missions of the armed forces. With few exceptions, the decisions made then continue to stand today.

Yet changes in technology, services organization, and a reorienting of the US military to peer threats from China and Russia have Air Force leaders talking seriously about a new roles and missions debate.

A redivision of labor among the services would address space and cyber, neither of which existed as warfighting domains 71 years ago, as well as new technological realities and operating concepts, and it would color in gray areas where roles and missions among the services overlap or are under served.

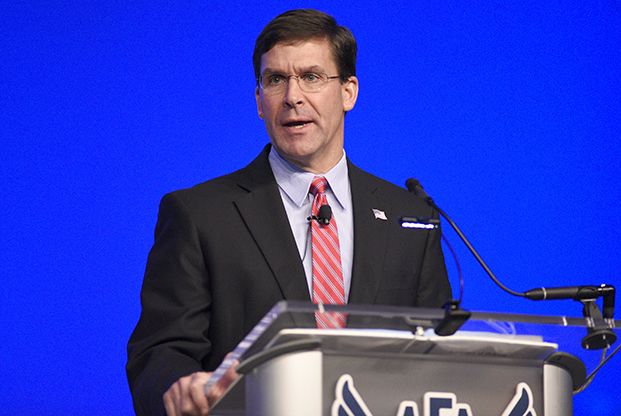

Defense Secretary Mark T. Esper, speaking at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference in September, said he’s leading two reviews of the Pentagon this fall: one on budgets, and the other regarding force posture and operational plans. That second review will focus on whether the services are “doing the right things,” Esper said. He said he’s not convinced the services are “optimized” in terms of where they are located and what they do, and specifically noted that the Air Force must be prepared for the “full spectrum” of kinetic and nonkinetic threats in multiple domains.

One area ripe for discussion is base defense. Air Force leaders at the conference said their new agile deployment concept will require deploying squadrons with ground-based air defenses, which means they would take up a role traditionally performed by the Army. Under the concept, small numbers of fighters and other aircraft would move rapidly from one austere airstrip to another, the better to complicate the dilemma for an enemy trying to target them with precision weapons. The Army has neither enough air defense systems to protect all those expeditionary units, nor are the systems small and lightweight enough to be rapidly mobile using minimal airlift.

Pacific Air Forces Commander, Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr., asked about the roles and missions debate, said, “We need to think about it.” The Army’s Patriot missile batteries and Terminal High-Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) systems are too unwieldy to lend themselves to USAF’s goal of moving a half-dozen fighters to a location supported by a single C-130 full of technicians and equipment, Brown said. A Patriot battery can fill up to seven C-130s.

“THAADs and Patriots take a lot of lift,” Brown said. He’s talking to Air Force Research Labs about systems that would be lightweight and based on lasers or high-powered microwaves.

Lt. Gen. Thomas A. Bussiere, commander of the Alaskan North American Aerospace Defense Command Region, which is part of NORAD, said USAF “absolutely has a requirement” for ground-based air defenses both at home and abroad. The range of China’s new missiles means there’s “no sanctuary” anyplace.

“We have to have the tools to engage that threat,” he said.

Mark Gunzinger, who led an Air Force-sponsored review of its future force structure for the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments earlier this year and now works for AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, said China would have an “easy job” of wiping out Air Force assets in the Pacific, concentrated as they are at a few well-known locations such as Guam and Okinawa.

The Army “does not have the resources it will need to defend our bases,” Gunzinger said. Air base defense “should be an Air Force role. The Air Force should take that on.”

ABORTED REFORMS

At the Key West meeting of 1948, the newly minted Defense Department hashed out who could have airpower, and for what ends. The Army got to keep helicopters and light aircraft for scouting and some intratheater transport, while the Air Force took over strategic and tactical functions, from bombers to close air support. The Navy was allowed to continue to have aircraft carriers and employ aircraft for almost any function, and kept its own ground force, the Marine Corps. The Navy had to give up its ambitions to conduct strategic bombing, including a “super carrier” program that would have been able to launch strategic bombers, while the Air Force got to proceed with its B-36 mega-size bomber.

Despite attempts to revisit the Key West deal through the years, it has largely remained unchanged. Congress last ordered the Pentagon to conduct a roles and missions review in 2008, when it directed the Defense Department to assign responsibilities for cyber; unmanned aircraft; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; intratheater lift; and “irregular warfare.”

The Pentagon’s 2009 response boiled down to an “every service for itself” approach, frequently using the phrase “each [service] has significant responsibilities” to explain the roles breakdown for each area under review.

The Air Force had sought to be the Executive Agent for unmanned aircraft in the runup to that review, arguing that its regular function of managing and deconflicting airspace above 15,000 feet made it a logical choice to guard against aerial collisions between manned and unmanned aircraft.

Yet even though the idea was endorsed by then-Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Adm. Edmund Giambastiani, at the time, then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates decided against it. Gates, who confessed abiding suspicion of the Air Force in his memoir, considered it a “turf grab,” and as a consequence, all the services have pursued their own unmanned aerial vehicle programs ever since. They’re supposed to be coordinated by a joint group, but it has no authority to shift resources between services or overrule a branch’s plans.

Space Force Bombers

The Pentagon is also working toward creating a sixth branch of the Armed Services—Space Force—that will have responsibility for conducting war in space. But space is an intrinsically multi-domain fighting arena. Ground stations that can launch rockets, high-energy lasers or microwaves at satellites are a direct threat to US space assets.

“Should Space Force have bombers to attack ground control stations? What about ground-based GPS jammers,” said retired Lt. Gen. Bruce Wright, president of the Air Force Association, and former commander of 5th Air Force and US Forces, Japan. “And what about ‘Rods from God’ We’ve known those are coming for a long time.”

Wright was referring to a concept explored in a 2005 Air Force

“Transformation Flight Plan” that foresaw 20-foot tungsten poles that, dropped from orbit, could pack the equivalent force of tens of thousands of pounds of TNT. Would Space Force be in charge of ground-based defenses against such hypersonic ballistic weapons? Today, the Missile Defense Agency is responsible.

In a February report on Space Force, DOD said the new service will “synchronize” space doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, education, personnel, facilities, and policies regarding the space domain. It will build “forces and capabilities,” be the service with the most space expertise, and be the “advocate for spacepower.” It will have the duty of “deterring aggression and defending the nation, US allies, and US interests from hostile acts in and from space, and make space capabilities available to all the other services as an enabling function.”

Most of Space Force’s specified duties make obvious sense. It will have responsibility for space launch, for example; detecting nuclear detonations in space; maintaining space situational awarenesss, etc. But Space Force bombers? The document says only that the new service would develop “prompt and sustained offensive and defensive space operations to achieve space superiority.”

A senior Air Force official said the wording was intentionally “left vague, because those are things we are still working through.”

A new roles and missions debate might not be just about the kind of operations the services undertake, but could also address how they divide geographic responsibilities. Last January, then-Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson and Chief of Staff Gen. David Goldfein penned an op-ed in which they noted that the Arctic is becoming increasingly contested as the ice melts and the sea becomes more navigable. They argued that heightened Arctic activity by China and Russia, the prospect of new resources in the region, and the Air Force’s concentration of a lot of its Pacific firepower in Alaska warrants a review of what the services are doing in the region.

“The 2019 National Defense Authorization Act requires an updated Defense Department Arctic strategy outlining the roles and missions of each service in the region,” they wrote. “World events and history suggest it’s time to move out smartly to protect our vital national interests.”

ARMY-CENTRIC THINKING

A new, formal roles and missions review would likely be led by Air Force Gen. John E. Hyten, Vice Chairman of the JCS, who has had an extensive career in the space business and knows as well as anyone what will be needed for a Space Force and missile defense. But Hyten will answer to Army Gen. Mark Milley, Chairman, who brings a ground-centric perspective to any new division of labor among the services.

Milley ruffled feathers with an interview he gave over the summer in which he outlined four “myths” of war. One of these, he said, is that wars can be won “from afar.” Americans have an unwarranted belief in technology, Milley said, and wars can only be won with “boots on the ground.” Technology merely allows the US to “shape battlefields and set the conditions for battle,” Milley asserted, “but the probability of getting a decisive outcome in a war from launching missiles from afar has yet to be proven in history.”

Had Milley missed Operation Allied Force, in which no NATO ground troops were deployed in combat, and yet Serbia was compelled to give up its ethnic cleansing campaign and withdraw from Kosovo by a NATO campaign conducted exclusively by air

Milley also said rapid mobilization for war is a fantasy, and that it takes a long time to generate the forces needed to prevail in a conflict. Yet the National Defense Strategy notes that the US will likely never again have the luxury of leisurely building up forces for an assault, with supplies and equipment brought by land, air, and sea, unharassed by enemy missiles or attacks. In the early days of conflict in particular, according to the NDS, the US will need to “win from afar.”

Esper said in his AFA speech that his reviews of the Pentagon are focused on tightly “aligning” the defense budget and the activities of the services with the NDS.

“Everything we do must be aimed toward achieving the goals and objectives of that strategy,” Esper asserted. It will likely be the best place for Milley to start in leading a new discussion of roles and missions.