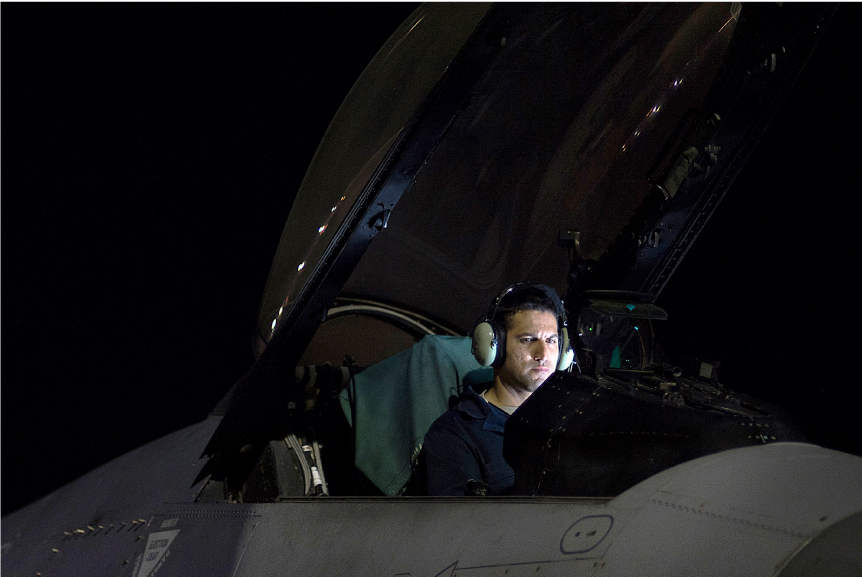

SSgt. Erick Vega, an avionics specialist, attempts to determine if his equipment was failing or if the space systems used by the F-16 were being attacked by simulated enemy forces during a Red Flag exercise in 2016. Photos: TSgt. David Salanitri; MSgt. William J. Buchanan/ANG; SrA. Thomas Spangler; TSgt. David Salanitri

“Blue Four is dead. Blue Four is dead.”

Believe it or not, this is a good radio call to hear—if it appears over the lava-baked shades of brown landscape north of Nellis AFB, Nev., as part of a Red Flag exercise, that is.

For more than 40 years, the desert skies of the Nevada Test and Training Range (NTTR) have reverberated to the roar of jet engines, the boom of live ordnance being dropped on the many targets scattered across the terrain, and some variation of the radio call mentioned above.

Which is entirely the point. Red Flag exists so that combat airmen—in particular, inexperienced wingmen known as “Blue Four”—can learn from their mistakes in training and not make them when an enemy is playing for keeps. Countless aircrews have undergone this training, and today new operators are being added to the mix. The definition of who is Blue Four is evolving rapidly.

Each new generation of American military aviators needs to learn the lessons written in blood from past conflicts and to develop their skills through realistic training opportunities such as a Red Flag. Equipment and tactics have evolved over time, and today’s warfare includes areas, or domains, that once weren’t considered vital in a fight.

Traditional wars were fought on the land, on and under the sea, and in the air. Today, warriors of advanced nations, and many from less so, and even nonstate actors, also go to war in space and cyberspace.

Using cyber attacks to disable an adversary’s command and control system can be just as effective (if not as satisfying or as permanent) as blowing it up. It also comes with a cost advantage: Cyber warfare can be much cheaper to wage and harder to attribute to an aggressor than it would cost for the US to send an F-35 or a B-2 to drop a guided munition on a target in response—if you even know who it was who attacked you in the first place. Not knowing for sure who attacked you or how or when they planned the strike most definitely crimps the options of leaders wanting to retaliate.

Space, meanwhile, hosts a unique blend of both hardware and computer software, on the ground and in orbit. The United States has invested many billions of dollars in its military space architecture to achieve a dominance in space-based information gathering. Other nations might not want the US to maintain that dominance and recognize the attractiveness of denying those capabilities.

If tomorrow’s Blue Four dies because he or she didn’t get the information needed about a deadly surface-to-air missile (SAM) site or the updated location of a high-value, but mobile, target, or is even given deliberately deceptive data, then past lessons from Red Flag will be for naught.

Enter today’s Red Flag, incorporating space and cyber into the exercise.

Space forces first officially played in a Red Flag in 2011, with the first operational Blue cyber participation in 2013. In each year since, at least once during the four annual exercises, space and cyber warriors join the scrimmage along with the pilots, weapon systems operators, air battle managers, combat search and rescue crews, intelligence personnel, and maintainers employed in today’s modern air combat domain.

Red Flag adversary forces today include not only the 64th Aggressor Squadron flying specially marked F-16s and the 507th Air Defense Aggressor Squadron replicating near-peer SAM systems, but also the 57th Information Aggressor Squadron (IAS) and the 527th Space Aggressor Squadron (SAS). The Air Force Reserves’ 26th SAS and the Kansas Air National Guard’s 177th Information Warfare Aggressor Squadron augment the bad guy forces as well.

The 57th IAS maps and mines the friendly Blue Force computer networks to discover useful information and disrupt Blue operations and support functions by degrading those same networks. The 527th SAS impairs GPS reception in the training range and disrupts Blue Force satellite-based communications.

At Red Flag 17-1

To fight their adversaries, the Blue Forces for 17-1, conducted Jan. 23–Feb. 10 of this year, had 98 aircraft ranging from the first operational F-35A squadron to B-1B bombers to F-22s, plus numerous dedicated space and cyber unit representatives. Other “firsts” for Red Flag included the inaugural appearance of the Royal Air Force’s RC-135 Rivet Joint aircraft and the RAF KC3 Voyager tanker.

However, a real issue for the meshing of space and cyber in the more traditional Red Flag is the different command and control required for these new domains versus the old-school jets-attacking-the-bad-guys scenario.

Red Flag, to date, has been a tactical-level event. Crews receive the tasking, mission plan the flight, execute, then debrief that mission. It is a self-contained world that focuses on a narrow part of a military campaign to achieve one specific objective.

That focus involves a detailed and long day spent mission planning. Once the tasking order has dropped, the mission commander works on a plan, coordinating all the assets allocated—air-to-air escort fighters, strikers/bombers, electronic attack and/or suppression of enemy air defenses, intelligence gatherers, command and control, and the all-important tankers—to accomplish the day’s tactical objective.

Adding space and cyber to the mix increases the level of difficulty of herding all those cats—and unlike the jets that deploy to Nellis, the infrastructure for space and cyber is largely fixed and located at various military installations around the globe. Thus, those units send liaisons to Red Flag who coordinate the mission commander’s direction into tasking for those at-home units. This link introduces another layer of complexity to the process.

A second difficulty affecting the integration of space and cyber capabilities into a Red Flag is the level of experience in the tactical leadership sent. While the overall mission commander is usually a field grade officer, or a very senior captain at the least, the package commanders are also usually more experienced leaders. During 17-1, however, the space package commander alternated between a junior captain and a first lieutenant.

Cyber participants had a similar level of experience for their portion of the mission. Participants indicated that the dichotomy of the junior officer having to interact with the much more seasoned officer led, initially, to a reticence to speak up on the part of the space operators and the cyber forces.

Learning nearly the Hard Way

Integrating such a disparate group is challenging and one of the biggest learning aspects of today’s Red Flag. Airmen must understand what each platform can and cannot do, dispelling misconceptions that many may have carried around. That satellite coverage depends more on Kepler’s law (regarding orbits) than Bernoulli’s principle (regarding fluid dynamics) is something that all must understand to be successful.

Just as a fighter might not have the gas to hang around for a long time waiting for a target to appear, a satellite might not be overhead at the exact moment the mission demands it see something critical; thus the effects desired simply aren’t available. Therefore, a contingency plan must be developed to achieve that mission. The learning involved is extensive and can’t be gained from academic study alone. Nothing brings urgency to a situation like looking a fellow warrior in the eye and promising, “I’ll get it done.”

However, regarding space, Air Force doctrine states, “Airmen should focus on employing space forces to achieve strategic and operational effects.” Cyber has similar caveats on its use. Those levels of effects are oftentimes removed from that tactical promise of “getting it done now.”

By definition, “strategic and operational” are spheres above the tactical. How to synchronize the effects of systems and capabilities that can affect far larger areas and bigger target sets than a tactical strike mission, while keeping the tactical flexibility needed to react to enemy actions, is a problem that not only Red Flag but the Air Force itself struggles with.

Lt. Col. Eric A. Flattem, the deputy commander of Red Flag, said during an in-brief to the participants, “DOD says we will win using multidomain command and control and execution. Now, they haven’t exactly spelled out how we are going to do that, but you guys are going to figure it out and show us and the department how it’s done.”

One officer who has had a leading role in figuring it out has been Col. DeAnna M. Burt, the 50th Space Wing commander at Schriever AFB, Colo., who was the first nonrated deployed wing commander for a Red Flag, specifically 16-3, held last year.

Burt said of just one of the challenges, “We had to look at the effects available from space, cyber, electronic warfare, and other nonkinetic capabilities,” asking, “how do we integrate those effects with the kinetic forces in order to achieve successful mission results.” Every target did not require a bomb, but every target did need to be dealt with using the forces available, she said.

A method for melding tactical with operational is via the command and control interface in the combined air operations center (CAOC). For Red Flag, the 505th Test Squadron conducts its own CAOC training in conjunction and coordination with the exercise itself. While the tactical crews concentrate on their particular piece of the day’s air war, the CAOC trains personnel for the operational level as executed in regions around the globe.

While Red Flag fliers perform their one mission per day—although there is both a day “go” and a night “go”—the CAOC uses the Red Flag mission as but one problem set to solve while it simulates a much larger and broader air war. It is in the CAOC that the space and cyber representatives operate, coordinating the desired effects for the Red Flag mission with their home stations where the actual operators of the satellites and servers are based.

These operators receive their tasking as part of a joint air and space tasking orders process, typically based on a three-day cycle, thus conforming more to the operational level of warfare’s timeline. That tasking order, once produced, is distributed to the units who are executing and fulfilling the tactical role and actually delivering ordnance on target.

Except in today’s multidomain fight, the ordnance might not literally go “bang.” Instead, it could prevent an adversary’s bang from harming allied aircrews or locating mobile threats and notifying inbound allied forces.

After the vul is over and dozens of jets have recovered back at Nellis, a many-hours-long process of various data-gathering commences, culminating in the mass debrief.

At the debrief, a gathering of nearly a hundred sweaty and tired aircrew join with the nonkinetic crews from the mission to assess what worked and what didn’t, and an overall computer playback is run to show the mission as it unfolded. Simulated air-to-air and surface-to-air shots are evaluated, and the effectiveness (or not) of each shot is studied.

In the recent flags, however, the space and cyber forces likewise traded shots with their Aggressor counterparts, determining who was successful in attacking or defending their networks and their ability to detect and work through GPS and satellite communication voice jamming. It’s not always the smoothest performance to observe, but the lessons gained far outweigh the occasional discomfort of having one’s mistakes revealed to the entire audience.

Finally, the errors are analyzed, and the resulting learning points are briefed to the audience, along with the recommended methods to avoid those missteps in future flights when the stakes might be for keeps.

“I think a lot of the players really learned a lot about the timing and tempo of all the effects and to layer them with kinetic tactics,” said Burt, from the 50th Space Wing. “We are talking about young captains, lieutenants, and airmen doing this, with this being their first exposure to a hectic combat ops type of experience. So what we are doing is not necessarily 10 combat missions but, rather, 10 full-up integrated multidomain missions to allow all of our airmen to go forward, should we have to fight a near-peer adversary someday.”

The complexity of this multidomain approach to warfare is an exponential expansion, compared to the more traditional battles that first established the need for Red Flag. Blue Four’s job is still to gain an everything-but-the-flak experience before facing flying lead, but today’s Blue Four cadre also includes those personnel not yet expert at controlling satellites or analyzing adversary computer networks.

Although those Blue Fours aren’t likely to die should something go wrong during an actual combat mission, their addition to today’s fight might just keep the original, airborne Blue Fours alive as well.

“You are here to learn how to better kill bad guys and break their stuff,” said the deployed 17-1 Red Flag air expeditionary wing commander, Col. Peter M. Fesler (then the 1st Fighter Wing commander at JB Langley-Eustis, Va., in his day job). During the first mass brief to the 17-1 personnel, Fesler said, “We all have to learn to integrate all of our capabilities to increase our lethality and to minimize our vulnerabilities.”

At Red Flag, this means the Air Force’s assets in air, space, and cyberspace must function as an integratedwhole.

_

Brick Eisel is a retired lieutenant colonel who served as an air battle manager in mobile radar units, E-3 AWACS, and E-8 JSTARS and is now a civilian Red Flag analyst. He is the author of two aviation nonfiction books, Beaufighters in the Night and MAGNUM! The Wild Weasels in Desert Storm. His last article for Air Force Magazine was “Tough Old Birds” in March 2006.