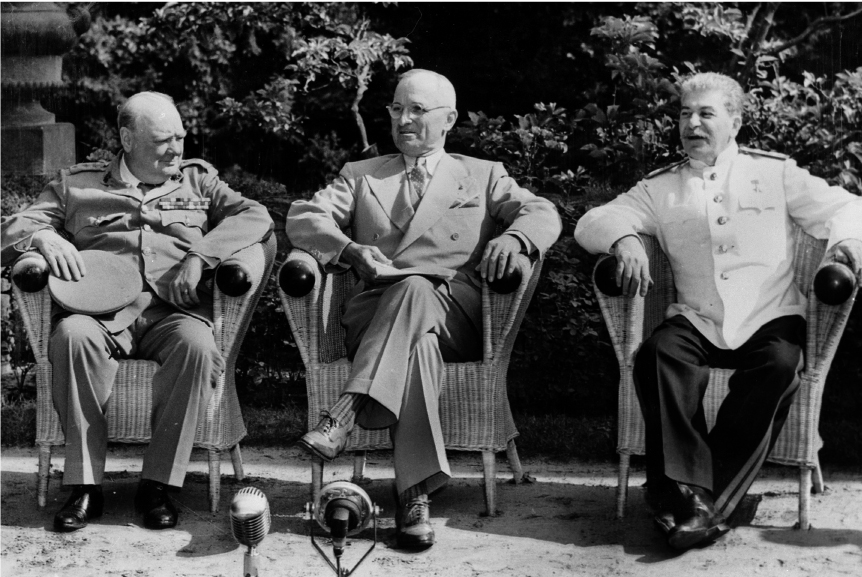

L-r: British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, US President Harry Truman, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in the garden of Cecilienhof Palace before meeting in Potsdam, Germany, in 1945. Photos: Truman Library via National Archives; Imperial War Museums

On July 7, 1945—two months after the German surrender and less than three months since he became President of the United States—Harry S. Truman boarded the US Navy cruiser Augusta at Newport News, Va. He was bound for Germany to meet with Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Great Britain and Marshal Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union to settle the future of Europe.

This third and last meeting of the wartime Big Three was to be held at Potsdam, a suburb of Berlin, from July 16 to Aug. 2. It followed conferences in Teheran in 1943 and at Yalta in February 1945.

At the two previous meetings, Allied leaders had reached tentative agreements on issues ranging from the postwar map of Europe to the degree of reparations to be imposed on Germany, but the final decisions were to be made at Potsdam.

In recent months, the situation had changed. With the war against Germany over, there was less need for the US and Britain to placate Stalin. And it was becoming increasingly clear—although not as clear as it would be later—that Stalin could not be trusted.

In many ways, Stalin held the whip hand in the disposition of control in Europe because the Red Army was in possession of conquered territory stretching as far west as the Elbe River, halfway across Germany.

The war against Japan continued in the Pacific, but that was more of a concern to Truman and the United States than to Churchill and Stalin, who were focused primarily on the balance of power in Europe.

Truman, who took office when Franklin D. Roosevelt died in April, had to learn fast. Roosevelt—who selected Truman as his running mate for purely political reasons in the 1944 election campaign—had told him almost nothing. During his short tenure as vice president, he was not included when important issues were discussed in the White House.

It was only after assuming the presidency that Truman learned the revolutionary secret he carried with him to Potsdam. The United States had developed an atomic bomb and was ready to test it at a remote site in the New Mexico desert.

Truman would not be the only new leader at Potsdam. Before the conference was over, Churchill would be gone as well, replaced as prime minister by Clement Attlee, who was as surprised as everyone else by the results of a general election back home.

Uncle Joe

Stalin seldom left Moscow and he flatly refused to venture beyond territory controlled by the Soviet Union. It was at his insistence that Potsdam was chosen as the location for the Big Three conference.

Potsdam, on the southwestern edge of Berlin and in the Soviet occupational zone, was relatively untouched by the bombing. It had been the capital of the German film industry before the war and numerous aristocrats and movie stars had homes there. The Russians evicted all Germans for the duration of the meeting.

Churchill and Truman arrived before Stalin did, giving them time to see the rubble and destruction of Berlin, including the Reich Chancellery, which had been Hitler’s headquarters. Churchill went down into the ruins of the Hitler bunker underneath the Chancellery, but Truman, traveling by a separate motorcade, did not.

Formal sessions of the conference were held in the Cecilienhof Palace, a spectacular 176-room country estate built in 1917 for Crown Prince Wilhelm and his wife, Cecilie. The Russians planted a huge Red Star of geraniums in the courtyard as a statement of power.

Up to the German surrender on May 8, the Americans and the British had set aside their differences with Stalin for the common purpose of defeating Hitler. A spirit of camaraderie prevailed and both Roosevelt and Churchill referred with some fondness to Stalin as “Uncle Joe.” Truman picked up the usage as well.

As recently as his return from Yalta in February, Churchill reported to the House of Commons that “Marshal Stalin and the Soviet leadership wish to live in honorable friendship and equality with the Western democracies. I feel also that their word is their bond.”

That perception had begun to wear thin as Stalin reneged on promises of free choice for liberated nations in eastern Europe. In his memoirs, Truman depicted himself as talking tough to the Russians. Indeed, there was some of that, but the main effort was toward cooperation.

Sitting alongside Truman at the table at Potsdam as diplomatic advisor was Joseph E. Davies, the former ambassador to the Soviet Union, noted for his uncritical admiration for Stalin. The current ambassador, hardliner Averell Harriman, was relegated to a seat in the second row with the staff.

“I can deal with Stalin,” Truman wrote in his Potsdam diary. “He is honest—but smart as hell.” In a letter to his wife July 29, he said, “I like Stalin. He is straightforward, knows what he wants, and will compromise if he can’t get it.”

Divergence of Interests

The Soviets had lost nearly a third of their national wealth and about 15 percent of their prewar population to German aggression. Stalin felt justified in stripping to the bone what was left of Germany for reparations.

Truman and the British, on the other hand, wanted to avoid the mistakes of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which officially ended World War I. The harsh conditions imposed on Germany stimulated the rise of Hitler and the Nazis. Punitive reparations destabilized the international economy and provoked an extreme backlash in Germany.

The Germans defaulted on the reparations in 1923, but US banks lent them enough money to make their payments to the French and British. Germany soon defaulted on the US loans as well. In 1933, Hitler canceled the reparations outright.

“We do not intend again to make the mistake of extracting reparations in money and then lending Germany the money with which to pay,” Truman said.

Truman’s most urgent objective at Potsdam was to obtain Russia’s entry into the war in the Pacific, where an invasion of the Japanese home islands was to begin in November 1946. The Russians, having their hands full in Europe, had never revoked a neutrality pact with Japan signed in April 1941. Stalin had promised to join the fight against Japan once Germany was defeated, but he had not yet done so.

Churchill’s chief concern was the balance of power in Europe. The Americans had served notice that their troops would be going home. With France and Italy out of action and British strength depleted by the war, there was no effective check on the Soviets by the Europeans themselves. Churchill hoped the United States would fill the gap.

In April, Churchill had objected vigorously when the Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, halted the US-British advance at the Elbe and left it to the Red Army to take Berlin. The postwar occupation zones had been decided already, and Berlin was 100 miles inside the Soviet sector. Eisenhower would not expend tens of thousands of casualties and risk a clash with the Russians for a prize that would be turned over to the Russians anyway.

At the time of the surrender, Allied troops held positions in parts of Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia that were designated for Soviet control. Churchill tried to persuade Truman to keep US troops in place instead of retreating back to the occupation zone boundaries established at Yalta.

Churchill thought it might be possible to gain concessions from Stalin by refusal to withdraw, but Truman refused to ignore the zone agreement, which was one of several struck previously when times were different.

Done Deals

The Soviets had provided most of the forces fighting Germany and they took most of the casualties. “More than 80 percent of all combat during the Second World War took place on the Eastern front,” said historian Geoffrey Roberts. “The Germans suffered in excess of 90 percent of their losses on the Eastern front.”

That greatly reduced the number of German forces available to oppose the US and British on the Western front, and it gave Stalin leverage in dealing with Roosevelt and Churchill.

Stalin pointed out that Russia had been invaded from the west three times, by Napoleon in 1812 and by the Germans at the beginning of both world wars. Now that he held what amounted to a large defensive buffer zone in Eastern Europe, he was not about to give it up.

“The Americans and the British generally agreed that future governments of the Eastern European nations bordering the Soviet Union should be ‘friendly’ to the Soviet regime, while the Soviets pledged to allow free elections in all territories liberated from Nazi Germany,” a US State Department historian said later.

As Stalin wanted, the Polish and German borders would be moved to the west but the final boundaries were not confirmed until Potsdam. At Yalta, it had been decided that substantial reparations would be levied against Germany with half of the total amount going to the Russians. How much the Russians would be allowed to take away would also be determined at Potsdam.

The lines of the occupation zones in Germany had been drawn in 1943. The first plan, called “Rankin (C),” was devised by the British, who offered it for consideration at Teheran. The eventual map for the occupation, with the Russian zone extending to the Elbe, was basically a British product and was accepted at Yalta.

Churchill’s push for the Americans to adopt a more aggressive stance at Potsdam ended when he was ousted as prime minister. The election was July 5, but the count was delayed until the votes from those serving overseas were in and counted. The expectation was that Churchill and his Conservative party would win. The British returned home for the tabulation on July 25, and to the surprise of all, Labour won by a big margin.

Labour leader Clement Attlee had come to Potsdam as deputy prime minister in the wartime coalition government. When the conference resumed July 28, he was prime minister. An outgoing Conservative official quipped that with the unprepossessing Attlee to represent Britain, the Big Three had become the “Big Two-and-a-Half.”

The Map of Europe

Configuration of nations in Eastern Europe changed repeatedly in the first half of the 20th century. When World War I began in 1914, the Russian empire included most of what had once been Poland and reached westward to abut the German state of Prussia.

In 1918, Soviet leader V. I. Lenin was desperate to get out of the war with Germany—which had been going disastrously for Russia—and concentrate on the revolution at home. Germany’s price for the armistice was that Russia yield a huge swath of its territory, giving Germany a new border 130 miles east of Warsaw.

The Versailles Treaty in 1919 re-created Poland as an independent country. The Poles, fired up by their new aspirations, attacked Russia. When the fighting ended in 1921, the Polish frontier had been pushed deeper into the Soviet Union, almost to Minsk.

The Poles lost all of that and more in 1939, when Poland was subjugated and divided up between Germany and the Soviet Union as a function of their short-lived nonaggression pact. In 1941, Germany invaded Russia from bases in its part of Poland.

At the time of the Teheran conference, the Soviets had defeated the invasion and were pushing the Germans backward. A Polish government in exile had set up headquarters in London, but any idea that Stalin would let Poland go once he recovered it was wishful thinking.

At Teheran and Yalta, for wartime unity and other considerations, Roosevelt and Churchill agreed to shift the Soviet-Polish border more than 100 miles to the west and to compensate Poland with the addition of a similar-sized piece of Germany on the eastern side.

By these actions, the Soviet Union recovered all of the territory that Lenin had given up under duress in 1918 and the western border of a subservient Poland was established a mere 50 miles from Berlin. The final word on the Polish-German boundary would be at Potsdam.

Roosevelt and Churchill recognized the injustice to Poland but the reality was that they could not do any better without risking a breach in the alliance and a major confrontation with Stalin.

The Explosion at Trinity

The US effort to pull the Soviet Union into the Pacific war had begun with Roosevelt. At Teheran and again at Yalta, he was willing to concede to Stalin territorial gains in the Far East—including the Kurile islands and half of Sakhalin Island—in return for joining in the war against Japan.

It was also a priority for Truman. “There were many reasons for my going to Potsdam, but the most urgent to my mind was to get from Stalin a personal affirmation of Russia’s entry into the war against Japan,” he said in his memoirs.

Truman was elated on July 17 when Stalin gave his promise. “I’ve gotten what I came for,” Truman wrote to his wife that night. “Stalin goes to war Aug. 15 with no strings on it.”

When Truman got the news of the successful atomic bomb test at Trinity site in New Mexico July 16, he told Churchill right away but did not inform Stalin until July 24. He avoided the word “atomic,” describing it to Stalin as a “new weapon of unusual destructive power.”

Stalin showed little reaction, and Truman and Churchill thought he did not understand the significance. In fact, Stalin was already aware of the atomic bomb from reports by the Soviet spy network in the United States. He had known about it before Truman did.

Soviet participation in the Pacific was still regarded as important. Truman’s military advisors were not convinced that the atomic bomb would be decisive and the plan to invade Japan was still on.

Truman was aboard Augusta 800 miles from Newport News when word came that the atomic bomb had fallen on Hiroshima. The Hiroshima bomb Aug. 6 and a second one at Nagasaki Aug. 9 induced a rescript of surrender from the emperor Aug. 15, but the Soviets—who had declared war on Japan Aug. 8—continued to advance through Manchuria, inflicting casualties and capturing territory, until the formal surrender Sept. 2.

Final Lines

The final arrangement at Potsdam managed to avoid the Versailles syndrome and the disastrous consequences of punitive monetary reparations. This time the settlement would be in kind rather than in cash. Germany’s remaining assets and industrial equipment, except for the minimum necessary for the peacetime economy, were subject to confiscation as wartime reparations.

Stalin claimed that the reparations he sought were equal to only 20 percent of the Soviet losses at the hands of the Germans.

The Russians stripped Germany clean to the extent they could. They had a free hand in their own zone but the formula for reparations entitled them to no more than 15 percent of the industrial equipment available in the western zones. To Germany’s good fortune, the industrial base was concentrated in the west.

Nevertheless, the Soviets dismantled and shipped 2,885 German factories to Russia. According to historian Michael Dobbs, the meticulous records kept by Soviet statisticians show that the booty carried away included 60,149 pianos, 458,612 radios, 188,071 carpets, 941,605 pieces of furniture, 3,338,348 pairs of shoes, 1,052,503 hats, two million tons of grain, and 20 million liters of alcohol.

The westward shift in the borders of Poland meant a change in nationality for almost 15 million people. Hordes of newcomers from the gaining nations surged into the transferred lands, pushing out the previous inhabitants and creating throngs of refugees in Eastern Europe. Many of these “displaced persons,” mostly ethnic Germans, crowded into the US and British zones.

In Poland and elsewhere, Stalin placed puppet regimes in power. He had achieved his objective of a defensive barrier between the west and the Soviet Union and then some. He had locked in control of a Soviet empire in Europe and there was nothing that the United States and Britain could do about it.

Truman took one additional accomplishment home from Potsdam. He had secured Soviet support for organization of the United Nations, which was a cherished goal of Roosevelt’s and now of Truman’s.

Legacies of Potsdam

Truman was not likely as optimistic as he sounded in his Aug. 9 radio report on Potsdam, in which he looked forward to a “just and lasting peace.” He said that “the three Great Powers are now more closely than ever bound together in determination to achieve that kind of peace. From Teheran and the Crimea, from San Francisco [where representatives of 50 nations met to draft the UN charter] and Berlin—we shall continue to march together to a lasting peace and a happy world!”

At Potsdam, the first clouds of the Cold War were already visible on the horizon.

In a speech at Fulton, Mo., in March 1946, Churchill declared that “an iron curtain has descended across the continent.” Truman was in the audience to hear him say it.

The best that Potsdam had been able to produce was the creation of two great power blocs that would face each other in an uneasy standoff for some 50 years.

However, Churchill’s hope at Potsdam for a new balance of power was fulfilled as Western Europe was rebuilt with aid from the Marshall Plan beginning in 1948 and US troops remained in Europe as part of the NorthAtlantic Treaty Organization, founded in 1949.

_

John T. Correll was editor in chief of Air Force Magazine for 18 years and is now a contributor. His most recent article, “Vietnamization,” appeared in the August issue.