Four Air Corps and Air Force Leaders and the Shadows that Remain.

Honorary promotions have existed in different forms throughout U.S. military history. In the 20th and early 21st centuries, honorary promotions for officers were normally authorized via legislation. However, not all such honorary promotions were accomplished this way—and perhaps not all were lawful as a result. The cases of William “Billy” Mitchell, Claire Chennault, James Doolittle, and Ira Eaker illustrate the process by which these promotions became standardized, the questionable motives and methods behind some of them, and the widespread failure of the Air Force bureaucracy to verify associated historical claims. Incorrect historical claims about honorary promotions raise questions about the official record and cast shadows over these air power heroes. These claims should be corrected to enhance public trust and counter misinformation.

“Tombstone promotions” first appeared at the turn of the 20th century and were not strictly honorary at their inception. Rather, these end-of-career promotions allowed officers to retire with the rank and pay of the next higher grade than the highest one they held on Active duty. Since beneficiaries either never held the rank in Active service, or held it only briefly, the higher rank often only appeared on their tombstone or retirement records—hence the term “tombstone promotion.” According to Rep. George Foss, the original motive was to “provide an incentive for voluntary retirement,” in order to reduce a backlog of officers in a given grade.

The Navy was authorized tombstone promotions by law in 1889. In contrast, the Army had no such authority, and simply retired many officers as generals with only nominal service in a given grade. In 1900, Rep. Thomas Jett observed that several recently retired brigadier generals had served in that grade for only one day. While the number of generals in Active service was capped, there was no such restriction in retirement, and at the time, no time-in-service requirement to retire at a grade. In 1904, Congress passed legislation permitting tombstone promotions for certain Army veterans of the Civil War.

Illinois Rep. George Foss, member of U.S. House of RepresentativesThe original motive was to “provide an incentive for voluntary retirement”… to reduce a backlog of officers in a given grade.

(1915-1919)

In the 1930s, several statutes authorizing tombstone promotions for veterans of World War I made the advancements strictly honorary, prohibiting higher pay or benefits. Blanket tombstone promotion authorizations continued through the 1950s, but in later years evolved to apply only to select retirement specialties, such as service academy department heads, senior military acquisition advisers, and assistant judge advocates general of the Navy.

For other deserving retirees, Congress started authorizing personal honorary promotions via joint resolution. Since these honorary promotions normally targeted individuals rather than entire ranks, this also meant that the motive had shifted to recognize individual service or achievement. In 2000, Congress established a process through which a member of Congress could request review of a proposed honorary promotion by a military secretary. If favorable, Congress would then authorize the promotion with a provision in that year’s National Defense Authorization Act. When the Office of the Secretary of Defense objected to the reporting requirement as “overly burdensome,” lawmakers in 2021 delegated authority to the department for honorary promotions up to major general. Honorary promotions to three- or four-star rank still require Congress’ consent.

William L. Mitchell

Col. William “Billy” Mitchell is an outsized figure among air power theorists, simultaneously “the most prominent American to advocate a vision of strategic air power” and “the single most … controversial figure in the history of American air power,” according to Air Force historian Roger Miller. In 1925, Mitchell was convicted by court-martial for charging that aviation accidents were “the result of the incompetency, the criminal negligence, and the most treasonable negligence of our national defense by the Navy and War Departments.” He was sentenced to five years suspension and half pay, but resigned rather than accept the punishment.

Mitchell had already held the temporary rank of brigadier general as Assistant Chief of the Air Service, but reverted to his permanent rank of colonel in 1925 after that appointment concluded. To the public, it appeared he had been demoted. In 1930, Congress authorized some former WWI officers to be advanced to the highest temporary rank they held during the war—a blanket tombstone promotion. This act did not promote Mitchell, as it required he be “retired according to law,” and Mitchell resigned, rather than retire. Instead, it permitted him to use the title of his highest wartime rank, enabling Mitchell to call himself a brigadier general even though he was a former colonel on official records.

Efforts to restore Mitchell’s rank or retirement began after his death in 1936, when Congress considered restoring him to the Army’s retired list. The proposal failed, however, when lawmakers could not square Mitchell’s strategic vision with his insubordination. This same problem repeatedly scuttled proposed legislation in the years that followed.

Perhaps the strongest push to restore Mitchell’s rank came in the 1940s. Two bills sought to make Mitchell whole; they specified that “his rank in War Department records should appear as that of brigadier general,” or that “William Mitchell was a brigadier general … at the time of his death.” Another bill added that “no pay, allowances, or other financial benefit” would flow from the promotion. None of the measures became law.

Efforts to promote Mitchell continued in vain into the late 1950s, when the director of the Air Force Records Center added a document to Mitchell’s personnel file claiming that “on 18 July 1947, a special bill was passed by Congress promoting General Mitchell to the rank of major general.” In fact, however, the bill only passed in the Senate on July 16, 1947; it never gained the consent of the House.

Mitchell’s promotion to major general was finally authorized in 2004, when Rep. Perkins Bass (R-N.H.), a relative of Mitchell’s, successfully inserted a provision into the FY05 defense bill. However, the promotion reportedly did not occur; congressional authorization merely permitted the action and could not require it be carried out. Air Force Lt. Col. William Ott reflected in the Air & Space Power Journal that the promotion would be “a pyrrhic victory,” since it would not “erase the questionable actions that proceeded from [Mitchell’s] passionate advocacy of air power’s independence.”

There is no dispute that Mitchell was never posthumously promoted. However, at this writing, the mistaken promotion claim still appears on the official Air Force website for Medal of Honor recipients. The website incorrectly claims that in 1947, “a special bill of Congress promoted him to major general.” Indeed, the claim that Mitchell is a Medal of Honor recipient is also untrue. Congress recognized Mitchell with a Congressional Gold Medal in 1946, not a Medal of Honor. The bill’s sponsor did not understand the difference, leading to the measure’s original language that would have authorized a Medal of Honor. The House Committee on Military Affairs discovered the error and amended the bill to remove all substantive references to the Medal of Honor, and clarified that “the legislation under consideration does not authorize an award of the Congressional Medal of Honor.” Nevertheless, the title of the bill—Authorizing the President of the United States to award posthumously in the name of Congress a Medal of Honor to William Mitchell—was never corrected, which understandably misled many readers.

The Air Force presumably advanced mistaken claims about Mitchell in good faith, but with many historical and legislative resources at their disposal, it is difficult to explain why these errors remain uncorrected.

Claire L. Chennault

The first Air Force general to be advanced in retirement was Maj. Gen. Claire Lee Chennault, who famously trained the Chinese Air Force during the Sino-Japanese War, and then commanded the Flying Tigers in China during World War II. Chennault retired in 1945, but received a retirement promotion to lieutenant general authorized by legislation in 1958. The fact that Chennault received this tribute despite a rocky relationship with his Air Corps colleagues can perhaps be attributed to his association with the influential anti-communist “China Lobby” of that period. Chennault was also immortalized in popular media—Air Force historian Col. Phillip Meilinger called him “one of America’s more famous Airmen.”

Chennault’s promotion was discernible from Mitchell’s in that it was not posthumous. After Chennault was hospitalized with terminal lung cancer, Congress passed the promotion bill “without objection or debate,” and officials “sped it to the White House” for immediate signature only hours later. Chennault’s promotion was far-less controversial than Mitchell’s, which undoubtedly helped to forge a legislative consensus. According to The New York Times, the promotion represented “a heartfelt vote of respect to the man.”

Chennault’s legislation specified, “no increase in retired pay or benefits shall accrue as a result of the enactment of the Act.” The House Committee on Armed Services specified that there should be “no cost to the government involved in the proposed legislation.” According to the committee, “the fact that no funds are involved” obviated the need for reports on the bill, and thus expedited its passage.

Finally, unlike Mitchell’s promotion, Chennault’s was actually carried out. This made it perhaps the first individual promotion of a retired officer that was strictly honorary, long before the process of honorary promotion was codified in law.

James H. Doolittle and Ira C. Eaker

Starting in the early 1980s, various individuals began to petition President Ronald Reagan to advance retired Lt. Gen. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle to the grade of four-star general. The effort was a successful and eventually was packaged with another retirement promotion for Lt. Gen. Ira C. Eaker. By this time, the pathway for authorizing honorary promotions had atrophied, which perhaps influenced the administration’s choices.

In April 1981, actor and retired Air Force Reserve Brig. Gen. “Jimmy” Stewart wrote to his friend President Reagan as part of a lobbying campaign to promote Doolittle to four-star general. Doolittle had many impressive qualifications, which led one Air Force historian to call him “the United State Air Force’s true Renaissance man.” His leadership of the so-called “Doolittle Raiders,” who bombed Tokyo in the spring of 1942, earned him the Medal of Honor. He later commanded the 4th Bombardment Wing, the Northwest African Strategic Air Forces, the 15th Air Force, and the 8th Air Force. Doolittle attempted to retire in 1946, but was convinced to revert to inactive Reserve status. Not until 1959 was his retirement finally accepted.

The promotion request was referred to the Air Force, but the service’s reaction was tepid. Air Force Secretary Verne Orr reflected that Doolittle had already received the Medal of Honor and that he did not necessarily deserve promotion compared to contemporaries like Lt. Gen. Eaker, whom Orr noted “had greater responsibilities.”

Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense John Rixse researched the proposed promotion and discovered the prior honorary promotion of General Chennault in 1958, which he considered “one precedent for this type of initiative.” But the department ultimately opposed the move. President Reagan informed Stewart that promoting Doolittle “might create disappointment and resentment that would outweigh the pleasure and favorable publicity of selecting one national hero for unusual promotion.”

Around the same time, however, Sen. Barry M. Goldwater also lobbied the President for Doolittle’s promotion, writing that “no one man living in America has done more for the science of flying.” Obviously aware of the administration’s position, he argued that “Jimmy Doolittle should take precedence” over other retired generals. Goldwater’s involvement was significant, because as a prominent senator he had an outsized influence on any legislative authorization. Goldwater was also a retired Air Force Reserve major general himself.

The repeated interest in Doolittle’s promotion drew another rebuttal from Orr, who wrote to the White House expressing that “in the past, all of the military services have guarded against using flag or general officer promotions as a reward for performance.” Evidently, Orr was unaware of Chennault’s promotion, because he added, “we have not made any posthumous or honorary general officer promotions in any of the services.”

A frustrated Goldwater wrote to Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles A. Gabriel in 1984, asking about potential blowback from the Doolittle promotion. Specifically, Goldwater wanted to know if the service could “come up with some way of regulation that can be made solid and permanent, placing an absolute limit on two-stars as the ultimate rank of a Reservist or a National Guardsman?” Goldwater was worried that the four-star promotion—unprecedented for a reservist like Doolittle—would potentially “open the lid” for other reservists to also seek promotion.

Lt. Gen. Duane H. Cassidy, the Air Force deputy chief of staff for manpower and personnel, reviewing the legality of the proposed promotion, wrote that the law “places a de facto cap on non-Active duty officers at two-stars.” Further, Cassidy noted that legislation made retired officers ineligible for promotion to general officer ranks, since it required that “officers be serving on Active duty.” Thus, promoting retirees would require either “a change in the law” or a congressional waiver, based on the precedent of promoting Chennault in 1958.

By this time the proposal to promote Doolittle also had grown to include Eaker who had many accomplishments during World War II, including commanding the 8th Bomber Command, the 8th Air Force, the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, and serving as the deputy commander, Army Air Forces and Chief of the Air Staff. He had likely been denied a fourth star because of his transfer out of the European Theater during World War II, which was perceived as a rebuke from the U.S. Army Air Forces Commanding Gen. Henry H.”Hap” Arnold. Ironically, Doolittle was Eaker’s replacement—Doolittle recorded that he was “pleased” that he had proven himself to the leadership, but also “sensitive about Ira’s feelings.”

Gabriel wrote to Goldwater expressing that he had convinced the Secretary of the Air Force to endorse the promotions, and that he agreed with Cassidy’s conclusion that “special legislation will be required to get Ira and Jimmy their fourth stars,” since the law “states specifically that officers must be on Active duty to be eligible for three- and four-star promotions.” He referenced the Chennault promotion, remarking, “I’m convinced that’s the right way to go.” Gabriel even had his chief of legislative liaison draw up a draft bill.

In October 1984, Goldwater informed Gabriel that the proposed legislation was doomed in that session, speculating that “at this late date, someone would for whatever reasons, object to it.” The resolution was thus delayed until January 1985, and reintroduced stating that “advancement . . . shall not increase or change the compensation or benefits from the United States.” Goldwater sent the draft to the Secretary of Defense for comment, even though it was authored by the Air Force.

The resolution passed the Senate on Feb. 21. However, Air Force officials recorded that it “[met] resistance in the House,” which led them to search for other options. Lt. Col. Andrew Pelak in the office of the deputy chief of staff for manpower and personnel claimed that both the Defense and Air Force General Counsel’s Offices believed Doolittle and Eaker could be promoted under “the appointment power of the President contained in Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution” (known as the Appointments Clause), although there were no legal opinions attached to evidence this claim. An added bonus, he believed, was that this would authorize “increases in retired pay.”

Pelak’s suggestion quickly ascended into orbit, presumably because it was back-channeled to Goldwater without significant staffing. Goldwater told friends he brought the proposal directly to President Reagan, telling him that “even though the Reserve rules prevent the additional third or fourth star,” he could ignore the statute and “promote anybody he wanted.” According to Goldwater, the nominations dropped and were confirmed by the Senate the very next day.

The strategy of seeking Senate confirmation was clearly uncoordinated, for it was not communicated to the Senate Committee on Armed Services. Weeks later, the committee incorporated Goldwater’s promotion resolution into a draft of the fiscal 1986 authorization bill, expressing that “there have been a number of cases in the past 20 years in which similar authority has been enacted into law.” However, the provision had already been preempted by its own sponsor and was removed from later drafts.

On April 26, Eaker was promoted at the Pentagon by Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Gabriel. In prepared remarks, Eaker thanked “the members of Congress” among other Air Force officials, suggesting that he misunderstood who was responsible. His biography, written by a former member of his staff in cooperation with the Air Force Historical Foundation, also incorrectly recorded that Congress “passed special legislation” authorizing the promotion.

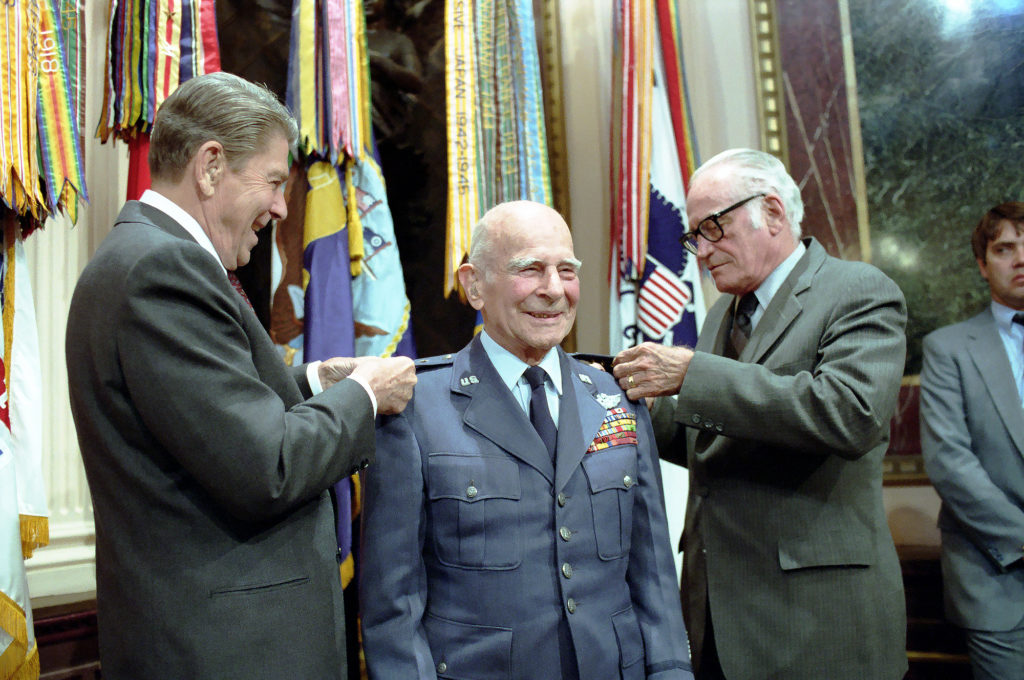

Doolittle was promoted by Reagan and Goldwater at the White House on June 13. Reagan thanked Goldwater “for his part in making this ceremony possible today.” An earlier draft of the speech also thanked Rep. Ike Skelton (D-Mo.), who along with Goldwater was credited in the speech’s border as being an “[initiator] of legislation.” Skelton’s name was removed after speechwriters ordered a legislative trace, which uncovered that the House had no involvement. The Los Angeles Times credited Goldwater at the time as the “sponsor of the legislation promoting the 89-year-old Doolittle,” suggesting that the administration left this authority opaque.

The authority behind the promotions was also distorted in multiple releases. An Air Force public affairs spokesman, quoted in the Washington Post, reportedly said this was “the first time [such promotions have] ever happened.” The Air Force biography of Eaker claims that “Congress passed special legislation awarding four-star status to General Eaker, prompted by Sen. Barry Goldwater.” Doolittle’s Air Force biography claims that “the U.S. Congress advanced him to full general on the Air Force retired list.” As the record clearly shows, Congress did not pass any legislation, and the full Congress was intentionally bypassed.

As Chairman of the Senate Committee on Armed Services, Goldwater certainly knew the promotions raised separation of powers issues, but it appears that any such concerns were subordinate to his own interest in Doolittle’s recognition. Goldwater originally informed Doolittle that “all we need to do is get the [promotion] bill through the House,” but then told him, “I went to the President . . . because of some complication that arose with my bill in the House.” He later explained that Senate confirmation was “a way around these scoundrels [in the House]” who wanted to “trade these promotions” for his vote on their “boondoggling projects.”

By way of authorization, Doolittle and Eaker’s promotion orders listed only the Constitution and Senate confirmation. While the attorney general had previously ruled that the President could appoint officers in violation of statutory provisions “in exceptional cases,” he also ruled that “Congress may point out the general class of individuals from which an appointment may be made, and may impose other reasonable restrictions.” In this case, the primary statutory restriction was to be presently serving in the military, and thus capable of actually occupying the office in question. This seems like a reasonable restriction that would not encroach on the President’s constitutional appointment authority. The Air Force leadership apparently reached the same conclusion, since they believed statutory provisions barred promotions of this type.

The promotions’ authority became even murkier in November 1986, when the Comptroller General reviewed them. He ruled that “when retired service members are advanced in grade on the retirement lists, their retired pay may not be recalculated … in the absence of statutory authority.” He noted that “there does not appear to be an Act of Congress authorizing a recalculation of the officers’ retired pay,” and “we are unaware of any provision of statute which would provide for a recomputation of their retired pay predicted on the action that was taken to advance them on the retired list.” While this ruling concerned only pay implications, it plainly contradicted the claims of Pelak, who argued Doolittle and Eaker would receive higher pay in retirement.

While the process for honorary promotions of retired members was not yet codified in 1985, a precedent already existed for legislative authorization, and there were many such promotions authorized later which passed both chambers of Congress. No case law exists on this precise issue, for a claimant must be denied promotion to have the standing and motive to litigate.

Conclusion

These case studies offer a window through the evolution of honorary promotions into present-day statutory provisions, as well as the questionable methods behind some promotion efforts. Some were driven by personal motives, which at times were likely conflicts of interest. Congress recently delegated the authority for honorary promotions up through major general, meaning that many defective honorary promotions of the past could be easily remedied without legislation. Unfortunately, this remedy would not apply to Doolittle and Eaker because of their ranks. As a result, reauthorizing those promotions would require Congress to waive public law, much like the aim of Goldwater’s unsuccessful resolution in 1985. Mitchell is another matter, as his advancement remains bound-up in his own impropriety. While that promotion has already been authorized by Congress, the effort appears to have been abandoned.

Air Force officials have not helped matters by building on false claims, such as Mitchell’s non-existent promotion to major general and false award of the Medal of Honor. Official biographies incorrectly state that Gens. Doolittle and Eaker were promoted under legislative authorization, when that is clearly not the case. With public trust in the federal government at record lows, the Air Force should correct the record, rather than contribute to misinformation.

Dwight S. Mears, JD, is a reference librarian with a background in history and law. A former Army officer and history professor, he focuses on strategy, policy, aviation, and military intelligence.This article was adapted from a version appearing in Air & Space Operations Review: Vol. 1, No. 4, Winter 2022.