How the Air Force awards aerial victory credits has changed over time. It will likely have to change again.

For many decades, the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala., has maintained the official aerial victory credits of the United States Air Force and its antecedents, the Air Service and the Army Air Forces, along with all the primary source documentation to confirm them. Victory credit is awarded for the downing of enemy planes in combat by aircrew flying manned aircraft. To gain credit, pilots need not necessarily shoot down the enemy; credit can also be awarded for maneuvering the enemy into the ground or forcing the pilot to bail out. But a witness or gun camera film must verify the loss.

Most American aerial victory credits were achieved by Air Service pilots and Army Air Forces pilots during World War I and World War II.

Confirmed kills took place in World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, in Operations Desert Shield/Desert Storm against Iraq, and operations against Serbia in the 1990s. All those credits were achieved in the twentieth century. Through two decades of war in Iraq and Afghanistan in the first two decades of the 20th century, American pilots never had the opportunity to shoot down manned enemy aircraft.

Over the years, the Air Force published separate lists of aerial victory credits for each war. The first, published in 1963, covered aerial victory credits awarded during the Korean War. In 1969, the Air Force published a list of World War I aerial victory credits. In 1974, the Air Force published its list of Vietnam War aerial victory credits. Not until 1978 did the Air Force first publish a complete list of World War II aerial victory credits. In 1988, working with Col. William C. Stancik, I compiled these into a single volume published by the United States Air Force Historical Research Center and Air University Press.

This list included aerial victory credits that had not been in the earlier compilations. In the 1990s, the Air Force published orders and aerial victory credit lists for those USAF pilots who shot down enemy aircraft over southwest Asia, in the conflict with Iraq, or over the former Yugoslavia, in conflicts with Serbia.

Most American aerial victory credits were achieved by Air Service pilots and Army Air Forces pilots during World War I and World War II.

The criteria for awarding aerial victories varied from war to war. Before the United States entered World War I, the British and the French were already engaged in aerial combat with the Germans, but their policy for awarding aerial victory credits varied. The British awarded each pilot who contributed to the downing of an enemy aircraft fractional credit. If two British pilots downed one enemy aircraft, each received half a credit. But in France, when two French pilots shot down one enemy aircraft, each received a full credit. Once the United States entered the war, it followed the more generous French system.

Famed U.S. Airman Capt. Edward V. Rickenbacker was the leading U.S. Army Air Service ace in World War I, credited with destroying 26 enemy aircraft. But in some cases, another pilot was also involved in the dogfight. The second highest scoring Air Service ace in World War I was 2nd Lt. Frank Luke, who earned 18 credits, some of them also shared. Many of the enemy aircraft Luke downed were balloons. Balloons would not count, however, in World War II.

The term “ace” originated in France during World War I and came to mean one who shot down at least five enemy aircraft. In some countries, being an ace meant a pilot had shot down at least 10 enemy airplanes.

Some American pilots volunteered with the French Air Service during World War I before the United States entered the war. Many of them served with the Lafayette Escadrille while others flew with the Lafayette Flying Corps. Since they were flying in French units and their aerial victory credits were awarded by the French Air Service, their aerial victories were never counted among Army Air Service aerial victory credits from World War I. After many of them later joined the Air Service, many of them collected American aerial victory credits for operations while flying in American units. Some earned both French and American aerial victory credits.

Deciding Victory Credits

The Air Force Historical Research Agency was charged with keeping the official lists of aerial victory credits that were awarded either by orders or by victory credit board reports, partly because those documents were also stored at the agency. Normally the agency would confirm which credits had already been awarded by a document and did not determine whether or not to award a credit based on other evidence. There is one exception. In the mid-1980s, the USAF appointed an aerial victory credit board composed of agency personnel, of which I was one, to decide whether the aerial victory credit awarded for the destruction of Adm. Isoruku Yamamoto’s aircraft was properly split between Thomas Lanphier and Rex Barber. Our committee was ordered not to consider evidence beyond what was originally submitted, and as a result, came to the same conclusion as earlier evaluators. Several years later, however, another board met to reconsider the case, this time adding newly discovered evidence, both from Japanese sources and from wreckage on the island of Bougainville. When the board deadlocked, with some wanting to keep the split credit, and others wanting to credit Barber and not Lanphier, Secretary of the Air Force Donald Rice upheld the original decision. Advocates looking to give Barber the whole credit tried to take the matter in court, where a federal judge ruled Rice acted within his authority and the decision was final.

The Air Force Historical Research Agency has also investigated cases in which a pilot, or someone advocating on his behalf, sought an aerial victory credit not included in official listings. In a few of these cases, historians have managed to uncover an order or an aerial victory credit board report that showed a credit had been awarded, but then overlooked. In those cases, credits could then be added to the official listings. But the agency does not have the authority to award a victory credit, even when there is compelling evidence to support it. All historians can do is furnish the relevant records should Air Force leadership appoint a board to look into the matter. One such case involved Lt. Gen. Charles Cleveland, a former head of Air University, who was awarded a fifth aerial victory credit in Korea by a 2008 review board in Washington, D.C.

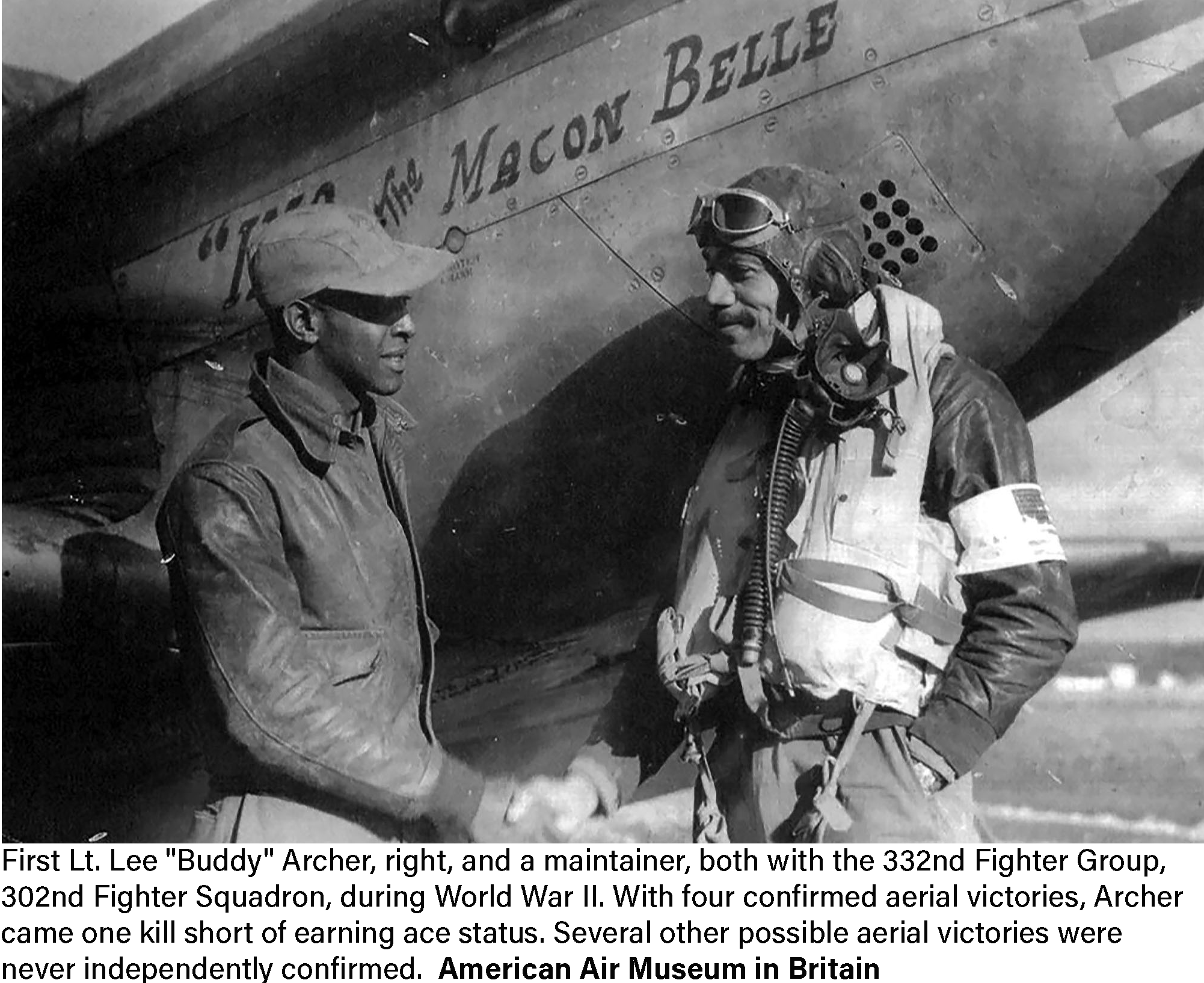

Another case involved Tuskegee Airman Lee Archer and a charge that he had been deprived of an aerial victory credit, blocking a Black pilot from becoming an ace. I and other agency historians diligently searched all the primary source documents related to the case, including histories of the 332nd Fighter Group with which Archer served, narrative mission reports of the group, Fifteenth Air Force orders awarding aerial victory credits, and claim statements. We were able to prove that Lee Archer destroyed four enemy aircraft, one on July 18, 1944, and three more on Oct. 12, 1944, and that he received credit for all four. We found no evidence of other enemy planes destroyed or that any of his victories had ever been taken away or reduced. Archer is one of four Tuskegee Airmen to have shot down three enemy aircraft in one day, and one of three to have shot down four enemy aircraft total. No Tuskegee Airmen ever became an ace.

Today, with the increasing use of uncrewed, remotely piloted aircraft, and a coming generation of collaborative combat aircraft, the question of how kills may be credited in the future remains open. Air Force F-15 pilots shot down Iranian drones in June 2017, one on June 8 and another on June 20, but because those aircraft were uninhabited, they did not earn aerial victory credits. Another USAF F-15 pilot is reported to have shot down another Iranian drone in September 2022. By the standards of the 20th century, no credit is deserved. But is it time to review those standards? That is up to Air Force leadership. In my opinion, ground-based pilots who shoot down unmanned enemy aircraft deserve credit, but in a different category from those who risked their lives flying in combat.

Largely because the United States entered the war late, in 1917, the war’s fourth year, foreign aces shot down more enemy airplanes than the Americans. Manfred von Richthofen was the leading ace of the war, credited with shooting down 80 enemy airplanes. French Capt. Rene Fonck was France’s leading ace, with 75 aerial victories. The leading British ace was Maj. Edward Mannock, with 73 kills.

In World War II, the U.S. adopted a system more like Britain’s: Two pilots contributing to the downing of an enemy aircraft shared the credit, with each getting one-half. For example, Thomas Lanphier and Rex Barber each received half a credit for shooting down the aircraft bearing Japan’s Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, leader of the Imperial Japanese Navy, because evidence showed both contributed to the demise of the airplane. Calculating victories this way more accurately aligned the number of victory credits with the number of enemy aircraft destroyed.

Army Air Forces Maj. Richard I. Bong, who flew a P-38 in the Pacific, was America’s top World War II ace, having shot down 40 Japanese airplanes. Close behind him was another P-38 pilot, Maj. Thomas B. McGuire, who shot down 38. Bong and McGuire knew that they were the leading aces and were engaged in a friendly competition to see who would end up with the most victories against Japanese aircraft. McGuire was shot down, perhaps (some have speculated), because he was so eager to catch up with or surpass Bong. The third-highest scoring Army Air Forces ace during World War II was Lt. Col. Francis S. Gabreski, who shot down 28 enemy aircraft. Gabreski’s mastery continued into the Korean War, where he earned credit for 6.5 more kills, finishing his career with 34.5. He was among many American pilots who served in both World War II and Korea and had confirmed kills in both wars.

About 690 Army Air Forces pilots became aces in World War II. Thousands contributed to 15,800 aerial victories during the war. Some 43 Army Air Force pilots downed five planes in a single day, notching five kills in just 24 hours.

The U.S. Navy kept its own list, identifying 380 aces during World War II. The highest-scoring Navy ace during World War II was Cmdr. David McCampbell, who shot down 34 enemy airplanes, including nine in a single day.

Other American aces represented foreign militaries. The “Flying Tigers” were American volunteers who served with the Chinese Air Force early in World War II, just after Pearl Harbor. Led by Claire Lee Chennault, who would eventually become commander of the 14th Air Force, the Flying Tigers tallied 286 aerial victories, all of which were recognized by Chinese rather than American orders. Some 20 Flying Tigers pilots became aces in Chinese service. Some of the volunteers later joined the U.S. military, including the 23rd Fighter Group of the U.S. Army Air Forces and the U.S. Marine Corps. Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, for example, went on to become the leading U.S. Marine Corps ace, shooting down 28 enemy aircraft.

Other American pilot volunteers served in the Royal Air Force, some of them in Eagle Squadrons set up before the U.S. entered the war. Some 16 of these became aces, their aerial victories awarded by the British. Squadron Leader Lance C. Wade led the pack, with 25. He was among five so-called double aces, credited with shooting down at least 10 each. Many of the American volunteers who had served with the Royal Air Force later served with the U.S. Army Air Forces, in the 8th Air Force and the 4th Fighter Group.

The leading ace of World War II, and the leading ace of all time, was the German pilot Capt. Erich Hartmann, credited with shooting down an incredible 352 enemy airplanes. Most of Hartmann’s victims flew for the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe. At the end of the war, the Soviets kept Hartmann a prisoner for over 10 years.

By the World War II standards, Rickenbacker would have had just 24.33 enemy kills, rather than 26, and Luke would have had 15.83, instead of 18.

Bomber gunners in four-engine B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators, and twin-engine B-25s and B-26s, shot down innumerable enemy aircraft, but keeping track was too difficult. Each B-17 or B-24 bomber had at least 10 machine guns and at least six gunners; bomber formations might include many dozens of aircraft. Trying to determine which gunner was responsible for shooting down a particular enemy aircraft was impossible. Very early after the Army Air Forces started counting its World War II aerial victories, it stopped attempting to award aerial victory credits to gunners in bombers, and their victories do not appear in the World War II listings because of the inability to determine who got what.

One exception was that both pilots and gunners aboard P-61 Black Widow night fighter planes received full credit for shooting down enemy aircraft in World War II. Because not all gunners were credited officially, the Air Force never included those who were in official compilations.

Generally, when fighter pilots returned from a mission, they would be debriefed, and intelligence officers would document fighter pilot claims of having shot down enemy airplanes. If those claims were later confirmed by witness statements or by gun camera film, the pilots received credit in official orders or public lists.

U.S. Army Air Forces never centralized those aerial victory counts. It would be years after that USAF historians compiled a single list with standard criteria. For every aerial victory credit, or fractional credit awarded, the historians prepared a data card showing the pilot’s name and serial number, unit, theater, and the incident date, along with the name of the other pilot or pilots if the aerial victory was shared, and references to confirming documents, such as an order or victory credit board report. Each line of the completed World War II victory credit list included the same information, except the reference to the confirming document and the name or names of the sharing pilots. There were seven World War II combat theaters: China-Burma-India, Central Pacific, Southwest Pacific, European Theater of Operations, and Mediterranean Theater of Operations, Alaska, and Iceland.

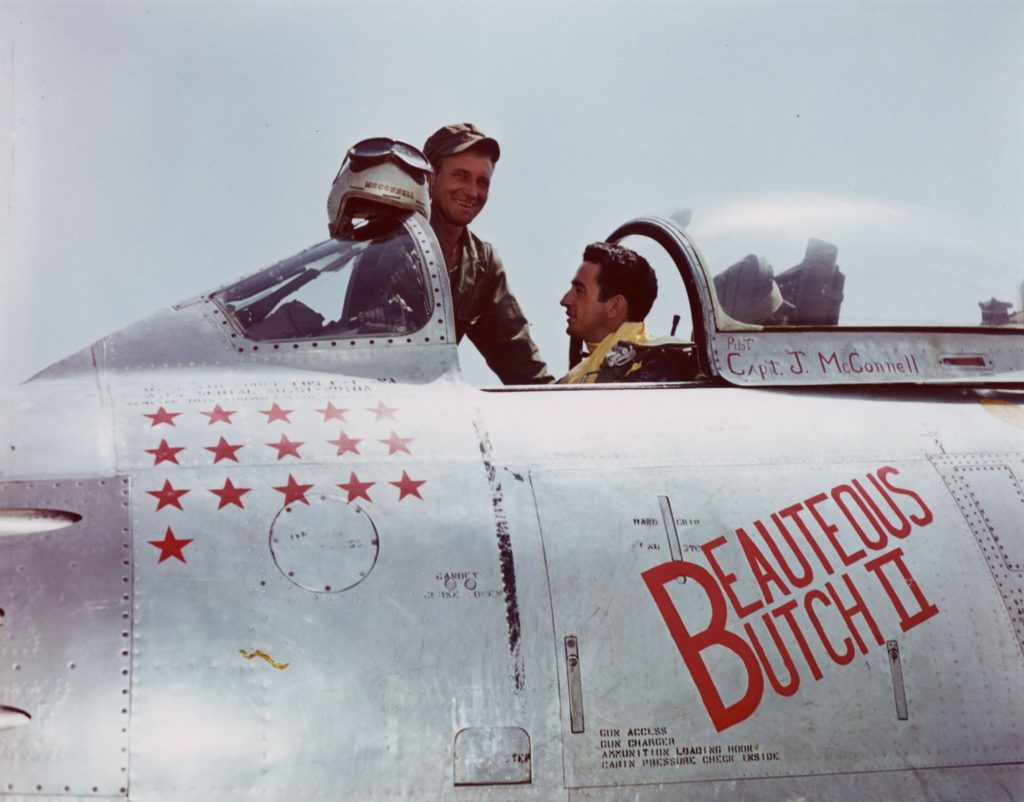

The USAF continued to split credits in the years that followed. Triple ace Capt. Joseph McConnell Jr. led U.S. Air Force aces in the Korean War with 16 enemy shootdowns, followed by a second triple ace, Maj. James Jabara, with 15. Jabara arrived in Korea having already earned 1.5 aerial victory credits in World War II.

Forty USAF pilots earned ace status in the Korean War with five or more shootdowns. Many other USAF pilots in Korea who scored aerial victories gained fame elsewhere, among them Marine Corps pilot Col. John Glenn, who shot down three enemy MiGs while flying F-86s with the Air Force. Glenn would go on to become the first American astronaut to achieve orbital flight and later become a U.S. senator. Air Force pilot Brig. Gen. Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin shot down two enemy planes during the Korean War and went on to be the second man to set foot on the moon.

During the Korean War, a few aerial victory credits were awarded to B-29 gunners. A typical B-29 bomber formation in that war included only four aircraft, with a maximum of four gunners per airplane, so claims could be verified more easily than in World War II.

In Vietnam, USAF’s aerial victory credit criteria changed again. Flying two-seat F-4 Phantom fighters, with the pilot in the front seat and the weapon systems officer (WSO) behind him, responsibility was shared: The pilot flew the plane while his backseater used radar to acquire the enemy target and then lock it in so the pilot could fire his air-to-air missiles accurately. Since shooting down an enemy required the work of both pilot and WSO, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. John D. Ryan directed that both deserved credit, not just the pilot. But instead of splitting the credit between them, as in World War II, both pilot and WSO received full credit. So, when an F-4 crew shot down one enemy aircraft, two aerial victory credits were awarded. Ryan had a personal connection to the issue: His son, who would follow his father decades later as Chief of Staff, was a WSO in Vietnam. In a sense, Ryan’s new policy marked a return to World War I criteria, and like World War I, adding up the total number of aerial victory credits awarded in Vietnam does not equal the number of enemy airplanes destroyed.

Two of the Air Force’s three aces in the Vietnam War were WSOs. Flying in F-4D and -E models, they shot down MiG 21 and MiG-19 enemy airplanes, using radar-guided AIM-7 Sparrow and AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles. Capt. Charles B. DeBellevue shot down six enemy airplanes, and Capt. Jeffrey S. Feinstein shot down five. The third ace was Capt. Richard S. Ritchie, who shared most of his aerial victories with DeBellevue, his frequent backseater. Ritchie is credited with downing five enemy MIGs, the last Air Force ace pilot from any conflict.

Two aerial victory credits were awarded in Vietnam to gunners in B-52 bombers. Just as during the Korean War, when a few aerial victory credits had been awarded to B-29 gunners.

POST-VIETNAM ERA

Not until 1991 would USAF pilots shoot down another aircraft. From 1991 to 1993, during Operation Desert Storm and subsequent air patrols, 29 USAF pilots shot down 38 Iraqi aircraft. F-15 pilots shot down 34 of those enemy aircraft, and F-16 and A-10 pilots shot down two each. Among the downed Iraqi aircraft were eight MiG-23s, six MiG-29s, six F-1 Mirages, four Su-22s, three MiG-25s, two MiG-21s, two Su-25s, two helicopters, two MI-8 HIPs, one Su-7, one PC-9, and one IL-76. Iraqi pilots did not shoot down a single USAF airplane in those engagements.

A few years later, in 1994, over the former Yugoslavia in Europe, two USAF pilots shot down four Yugoslavian Galeb airplanes. One F-16C pilot shot three, and another one; both were with the 526th Fighter Squadron of the 86th Fighter Wing. Five years later, in 1999, four USAF fighter pilots, three flying F-15Cs and one flying an F-16CJ, shot down five Serbian MiG-29s with ATM 120 air-to-air missiles.

KILL RATIOS

The kill ratios, or the ratio of aircraft American pilots shot down compared to the number of American aircraft shot down by enemy aircraft, changed with each war. For every six enemy aircraft shot down by USAF pilots during the Korean War, the Air Force lost one. In Vietnam, the ratio was just two kills to every loss. But during the 1990s, USAF pilots shot down 47 enemy Iraqi or Serbian planes without a single loss. Superior training, tactics, and technology made the difference. Indeed, some of those aerial victories were achieved beyond visual range, with documentation by means of digital records showing the trajectory of missiles approaching targeted enemy aircraft miles away, a completely different scenario than the close-in dogfights of World War I and World War II, when pilots not only saw each other’s aircraft, but sometimes could even look into the eyes of their opponents.

Daniel L. Haulman is a former head of the organizational histories branch of the Air Force Historical Research Agency. The author of several books on the Tuskegee Airmen, his “Misconceptions about the Tuskegee Airmen,” was published earlier this year. His most recent article for Air & Space Forces Magazine, “The Tuskegee Airmen, Heroes of War and Peace,” appeared in the January/February 2023 edition.