Of all the potential flashpoints that could explode into full-scale hostilities between the United States and the People’s Republic of China, one of the most dangerous would be a confrontation in the South China Sea. That channel between the Pacific and Indian Oceans is the site of intense nationalistic, economic, and strategic conflict—and is a murky scene, filled with chances for miscalculation.

| ||

|

An F-15 takes off, passing two E-3s on the ground at Andersen AFB, Guam, during the 2010 Valiant Shield exercise. Andersen is situated some 1,700 miles from the South China Sea. (USAF photo by A1C Jeffrey Schultze) |

The critical issue is access to the sea-lanes in one of the globe’s busiest waterways. More than half of the world’s shipping passes through the South China Sea every year, more than through the Suez and Panama Canals combined. Some 70,000 ships carrying $5.3 trillion worth of goods moved along those sea-lanes in 2011. Of that, $1.2 trillion worth was trade that directly affected the US. An estimated 80 percent of China’s imported oil for its surging economy comes though the SCS. Altogether, shipping through the sea is essential to the economy of every nation in North America and East Asia, including allies such as Japan and South Korea.

Strategically, free passage through the SCS is vital to US military operations in East and South Asia. American warships frequently sail through the sea on their way from the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean and back. The denial of this sea line of communication would require ships to sail south around Australia, which would add two weeks or more to transit.

The People’s Republic of China maintains that it has “indisputable sovereignty” over this sea and therefore can determine who can have access to it. The PRC contends the historical record shows that the SCS has been an internal waterway for centuries. Even when China was ruled by the Kuomintang, or Nationalists, before the communists came to power in 1949, China contended the SCS was Chinese.

Chinese officials have repeatedly demanded US warships not maneuver in the SCS, particularly when training with Southeast Asian navies. Occasionally, China has harassed US ships, in violation of international maritime rules. China does not recognize the claims of Southeast Asian nations to exclusive economic zones under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Freedom of Navigation

| ||

| (Staff map by Zaur Eylanbekov) |

On the opposite tack, the US and most of the nations around the sea’s periphery argue that the SCS is an international waterway through which freedom of navigation is guaranteed by long-standing maritime rules and traditions. US Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton has repeatedly asserted the US will defend freedom of navigation in the SCS. Similarly, Secretary of Defense Leon E. Panetta has stressed “the United States’ enduring commitment to freedom of navigation and … our support for a common approach to maritime security that is consistent with international law and norms.”

The US is not a signatory of the UNCLOS but successive Administrations have stated the US will abide by its provisions.

The People’s Liberation Army, which comprises all of China’s armed forces, has widened its scope of operations to include the South China Sea. China’s South Sea Fleet has become the nation’s largest fleet. It has a new base on Hainan island in the northwestern SCS.

At the same time, other Chinese government agencies have asserted jurisdiction in the sea. The Chinese refer to these agencies as the “Nine Dragons”—after a myth about dragons that stir the sea. A research report by the International Crisis Group (ICG) actually listed 11 “dragons,” including the PLA Navy, Bureau of Fisheries Administration, China Marine Surveillance, and the Foreign Ministry, plus three local coastal governments and several law enforcement agencies.

| ||

|

China’s first aircraft carrier will join its South Sea Fleet, based at Hainan island. A former Soviet aircraft carrier that the Chinese have named Shi Lang, the ship is depicted in this artist’s concept with J-15 fighter jets—the carrier version of the J-11B. (Image via chinesemilitaryreview.blogspot.com) |

“Most of these agencies were originally established to implement domestic policies but now play a foreign policy role,” the ICG states. “They have almost no knowledge of the diplomatic landscape and little interest in promoting the national foreign policy agenda. This focus on narrow agency or industry interests often means that their actions have significantly detrimental effects on foreign policy.” In addition, the report states, “Certain hardline academics and retired military officers have taken a high-profile role in promoting an assertive handling of territorial and maritime economic disputes.”

The potential for confrontation in the SCS is also complicated by the national interests of a dozen nations within a vast triangle centered on the sea and running from Japan south to Australia and west to India. Most of these nations have claims to unmeasured deposits of oil, gas, and minerals under the sea but within their exclusive economic zones. Many of these claims are competing and overlapping. In addition, the SCS is rich in fisheries that provide essential food to nations whose shores are washed by those waters.

Another complication arises from the piracy that persists in the SCS and the straits connecting it with the open oceans, despite improved coordination among littoral states in counterpiracy patrols. The International Maritime Bureau’s Piracy Reporting Center, which tracks piracy from its base in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, reported 58 attacks by pirates in the first half of 2012 alone, 32 of them in Indonesian waters. The bureau noted that many attacks might not be reported because that would cause insurers to raise rates.

| ||

|

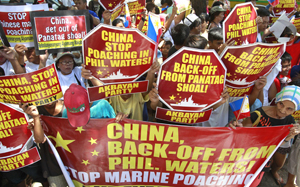

Protesters hold a rally outside the Chinese Embassy in the Makiti district of Manila, Philippines, during the standoff between Philippine and Chinese vessels at Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea. (AP photo by Bullit Marquez) |

Another, more intangible, complication is the legacy of colonialism. Until World War II, except for Japan and Thailand, most of the nations surrounding or near the South China Sea were subject to a colonial power. All became independent after the war but the memories of colonialism are still powerful, and national sovereignty is taken very seriously. This, in turn, often makes nations around the sea reluctant to engage in multilateral operations that they think might impinge on their independence.

Red Lines Drawn

In contrast to the SCS, issues surrounding potential conflicts across the Strait of Taiwan or on the Korean peninsula are fairly straightforward. “The red lines are drawn,” said an officer at US Pacific Command, “and we know where they are and the Chinese know where they are.” In and around the South China Sea, however, the US shows the flag not through permanent bases but by engagement, exercises, and joint training. These operations are intended to reassure American allies and friends and deter potential adversaries. The number of cooperative military exercises is increasing.

In nearly 150 exercises last year, PACOM and its components not only trained troops and leaders but left few footprints and thus precluded most of the problems that often arise when large numbers of US forces are permanently stationed in foreign lands. The US troops arrive by aircraft or ship, go through their paces with the forces of the host nation, then get back on the airplane or ship and go away.

The threat to the SCS and the potential for a confrontation with China was partly behind the Obama Administration’s call for a “pivot to the Pacific”—although the White House, Pentagon, and State Department have insisted that the fresh US emphasis on Asia was not aimed at China. Both in public and inside the Pentagon, the Administration has pledged to give priority to the Asia-Pacific region.

| ||

|

USAF Capt. Russ Kirklin refuels his B-52 from a KC-135 in preparation for the US-Australian Exercise Talisman Sabre in 2011. Australia remains an important ally as the US turns its attention toward the western Pacific. (USAF photo by SrA. Carlin Leslie) |

US forces are looking for ways to build trust in the region by sharing intelligence on the SCS with Southeast Asian nations that lack the capacity of US forces. Specifically, Terminal Fury is PACOM’s premier exercise to train the commander and staff in crisis planning and executing war plans. This year’s drill focused on space, cyber operations, and the SCS. A second operational exercise is Valiant Shield, which trains air and naval leaders to defend island nations in East and Southeast Asia.

Of America’s allies and partners, Australia is among the oldest and most steadfast—and has become even more vital as the US focuses on the South China Sea. Among the main USAF exercises in Australia are Pitch Black, which gives aircrews experience in offensive operations in a coalition, Talisman Sabre, which drills airmen in short warning, power projection, and forcible entry operations, and Cope North, which has USAF, Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), and Japanese Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) aviators flying together out of Andersen Air Force Base on Guam. The RAAF also has access to air bases in Malaysia from which they fly surveillance missions over the SCS and Indian Ocean.

Looking to the future, PACAF has sent teams to evaluate sites in Australia with the focus on increased rotations of USAF aircraft to bases in the north, namely RAAF Darwin and RAAF Tindal, to enable a more robust training and exercise program with the Australian Defense Force. And PACAF is mulling over the posting of an RAAF liaison officer in Hawaii.

On the Australian side, the Australian Defense Posture Review, done by an independent panel and released in May, recommended that the US be permitted to rotate more bombers, tankers, and surveillance aicraft, including the unmanned Global Hawk, through northern Australian air bases.

| ||

|

Republic of Singapore F-16s fly in formation over Darwin, Australia, after a sortie for the multinational exercise Pitch Black in 2010. Training included weeks of air combat operations with aircraft from Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, and the US. (Photo via the Australian Government Department of Defense website) |

Among the other services, the US Marines have started company-sized rotations of 250 troops to Darwin, in northern Australia, and plans to gradually expand these deployments to 2,500 marines at a time.

The Navy plans to make more frequent port calls to Australia and to expand exercises, as Australia’s defense review suggested that existing Navy bases on Australia’s west coast could support more US Navy port calls.

The US Army is considering more joint exercises with the Australian Army but will not duplicate what the Marines are doing. “Permanent US military bases will not be established in Australia,” the defense review makes plain however.

The US is also expanding defense ties with Singapore, Indonesia, and other regional powers with an eye toward overcoming the tensions in the South China Sea.

Singapore has constructed a pier to service US aircraft carriers and built an operations center compatible with that at PACOM. The city-state has invited the US to deploy up to four littoral combat ships at a naval base there. The first deployment is tentatively scheduled for next spring. Because air space around their country is so limited, Singaporean F-16 pilots train at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona, and other aviators train in Australia.

Much Ado About Nothing

A tense standoff between China and the Philippines over uninhabited rocks in the middle of the SCS began in April and continued into the summer to illuminate the issues stirring that sea and to underscore the risks of miscalculation. It was, said Robert C. Beckman, a Singapore-based scholar specializingin SCS issues, “a classic case of a territorial soverignty dispute.” The rocks, known as Scarborough Shoal after a ship wrecked there in the 18th century, are called Panatag by the Philippines and Huangyan by China.

| ||

|

Royal Australian Air Force Cpl. Phil Spencer secures equipment from a USAF C-17 near Williamson Airfield in Queensland, Australia, during Talisman Sabre in 2011. The exercise improves interoperability and combat readiness. (USAF photo by SSgt. Lakisha A. Croley) |

China has issued a legal brief arguing that it “first discovered Huangyan Island, gave it the name, incorporated it into its territory, and exercised jurisdiction over it.” The brief says, “In 1279, Chinese astronomer Guo Shoujing conducted a survey of the seas around China under the commission from his Emperor Kublai Khan, and the Huangyan Island was chosen as the point for surveying the South China Sea.”

The Philippines’ claim doesn’t go back quite so far, but does assert that the islands belonged to the Philippines during the 300 years of Spanish rule that ended in 1898. Officials in Manila point to maps drawn in 1734 and 1792 to make their case.

In April, the Philippines tried to arrest Chinese fishermen and vessels for poaching in the Philippine EEZ. China sent three maritime surveillance ships to defend the fisherman and the Philippines responded by dispatching two Coast Guard vessels. The standoff was eased by bad weather, with both the Filipinos and Chinese sailing away. In July, however, the Chinese sent four maritime surveillance ships into the SCS to assert sovereignty over those waters. They confronted a Vietnamese ship they accused of violating Chinese territorial waters and forced it to sail home. A spokesman in Beijing left open the possibility that warships would be deployed in the SCS.

The Philippines, other littoral states, and the US have called for negotiating a peaceful settlement of this and other similar disputes. The Chinese have contended that those are Chinese waters and there is nothing to negotiate. Further, they have demanded that any dialogue over issues in the SCS be bilateral—between China and another Asian nation—because Beijing does not want to be confronted by a unified multilateral proposal for a code of conduct governing use of the SCS.

Lastly, the Chinese have demanded that the US not be included in any discussion of the SCS, asserting that this is an Asian problem. Clinton and Panetta have been equally forceful in stating that vital US national interests are involved in the SCS and that the US expects to be part of the solution even though Washington will not take sides on competing sovereignty claims.