There will be no “gut-wrenching, nine-G turns” in the Air Force’s program during the next few years, according to the USAF Chief of Staff, Gen. Ronald R. Fogleman. The service’s budgets figure to stay fairly constant–perhaps even move upward a bit–and the seismic shifts in force structure and personnel that marked the first half of the 1990s have ended.

This dawning era of stability, however, will be marked by steady evolution of the force into something new, which might not closely resemble today’s Air Force. “We are no longer the Cold War Air Force,” said Air Force Secretary Sheila E. Widnall, who then added, “More importantly, we are no longer the post-Cold War Air Force.”

The Secretary explained, “We have worked through the ‘drawdown era’ to preserve our core competencies, to protect our people, and improve our readiness.” The Air Force, she said, is “postured to execute fully our role in the national military strategy, . . . and we have a clear vision of the road ahead.”

That “vision” will be fully articulated this fall. The Air Force is expected to complete a broad-gauged, eighteen-month study that will prescribe what it needs to do now and in years just ahead if it is to be fully capable, properly sized, and well equipped in 2025.

The conclusion of the USAF study will coincide with the start of what the Pentagon is calling its “quadrennial strategic review,” a successor to the Clinton Administration’s 1993 Bottom-Up Review of Defense Needs and Programs. That review determined that US armed forces should be capable of fighting and winning two major regional conflicts (MRCs) at about the same time. It established force levels that it said would support the two-MRC strategy.

The conclusion of the USAF study will coincide with the start of what the Pentagon is calling its “quadrennial strategic review,” a successor to the Clinton Administration’s 1993 Bottom-Up Review of Defense Needs and Programs. That review determined that US armed forces should be capable of fighting and winning two major regional conflicts (MRCs) at about the same time. It established force levels that it said would support the two-MRC strategy.

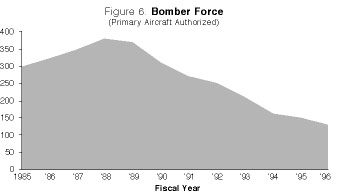

The BUR set USAF force levels at twenty fighter wing equivalents (FWEs) and up to 184 operational heavy bombers. Today the Air Force has twenty FWEs, of which thirteen are active and seven belong to the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard. There are about 150 bombers–100 of which are operational and the rest in a semi-inactive status. USAF also made other critical reductions. (See Figure 4)

The Guiding Light

Billed as a “synergistic” product of several studies of potential technological and political developments, the Air Force vision will be used to chart the course for everything from modernization investment to training, General Fogleman said.

“I know how precious the dollars will be” in the future, said the Chief of Staff, “but I don’t want [the review] to end up being a ‘shopping list'” of programs to buy. He expects the vision statement to encompass what the Air Force means to the country, what it brings to the equations of defense and power projection, and how it can deliver on its “core competencies.”

“I know how precious the dollars will be” in the future, said the Chief of Staff, “but I don’t want [the review] to end up being a ‘shopping list'” of programs to buy. He expects the vision statement to encompass what the Air Force means to the country, what it brings to the equations of defense and power projection, and how it can deliver on its “core competencies.”

“The program we have right now is pretty good,” General Fogleman added–and he said he does not expect the vision statement to trigger a sudden, radical departure from the way USAF has mapped its future and proposes to do business. At first, the vision statement will likely have minimal impact on everyday life in the Air Force, he said. Yet, the General said he is “anxious to get going” on the task of steering investments toward the technologies and methods that will keep USAF a dominant military force well into the future.

Maj. Gen. John W. Handy, USAF director of Programs and Evaluation and therefore a key figure in planning, asserted that the Air Force already is benefiting from the effort of crafting the design of the service three decades hence. “Last year,” said General Handy, “. . . we did not have the sense of vision into the future that we have this year; . . . and the clarity next year will be even better” regarding where USAF should apply available resources.

USAF’s vision will do more than simply give it a roadmap for developing technologies necessary to maintain future control of air and space, General Handy said. “Once people get caught up in it, they get excited, and light bulbs start going on over their heads.”

Resources appear to be leveling off, said officials. The Republican-led Congress showed every sign this spring of honoring not only most of the Air Force’s spending priorities but also much of its “wish list” of items it could not afford under its Administration-imposed budget “top line.”

Resources appear to be leveling off, said officials. The Republican-led Congress showed every sign this spring of honoring not only most of the Air Force’s spending priorities but also much of its “wish list” of items it could not afford under its Administration-imposed budget “top line.”

The near-term Air Force budget priority continues to be the C-17 airlifter. Key Congressional committees approved going ahead with a multiyear procurement that would pare five to ten percent off the per-airplane price.

USAF’s midterm priorities center on obtaining a variety of conventional weapons upgrades to the Air Force’s fleet of heavy bombers, supplying all its combat aircraft with smart and standoff munitions and laying the groundwork for the F-16’s replacement, the Joint Strike Fighter.

The new F-22 air-superiority fighter remains by far the highest Air Force spending priority for the long term. Meanwhile, the Air Force’s “ongoing” priorities include upgrades to space-launch systems and spacebased warning capabilities.

The Top Ten

General Fogleman, in testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee, listed USAF’s top “unfunded” requirements, in order of importance:

- More E-8 Joint Surveillance and Target Attack Radar System (Joint STARS) aircraft.

- F-15 fighters to offset attrition.

- F-16 fighters to offset attrition.

- Additional Global Positioning System (GPS) equipment.

- Improvements to E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System aircraft.

- Reengining of existing AWACS airplanes.

- More RC-135 Rivet Joint electronic surveillance airplanes.

- Additional digital crosslinks, such as the Joint Tactical Information Distribution System.

- More C-130J intratheater transports.

- More precision guided munitions.

General Fogleman said that priorities were assigned by regional commanders in chief, who value the capabilities of Air Force intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms.

General Handy said that the Fiscal 1997 budget sent to Congress in March reflects “continued attention to ‘Global Reach, Global Power,'” the Air Force’s 1990 white paper. He noted that the paper’s basic elements are sustaining deterrence, providing versatile combat capability, providing rapid mobility worldwide, controlling space, and building US influence. A new element–“added in the last twenty-four months”–is “ensuring information dominance.” [See “The New World of Information Warfare,” June 1996.]

|

Figure 4: The Air Force Drawdown, 1985-2001 | |||

| Aircraft purchases | Down 73 percent | ||

| Aircraft inventory | Down 29 percent | ||

| ICBM inventory | Down 47 percent | ||

| Major overseas installations | Down 68 percent | ||

| Major US installations | Down 26 percent | ||

| Active-duty end strength | Down 38 percent | ||

| Civilian end strength | Down 38 percent | ||

“It’s amazing how that has increased tremendously in importance . . . in everything we do,” General Handy observed. So critical has it become to preserve access to information–while denying it to an enemy–that “Global Awareness” will likely be added to “Global Reach, Global Power” as the Air Force’s semiofficial motto.

Resource priorities have changed since last year, noted General Handy. He said that the latest Defense Planning Guidance, prepared by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, still gives top priority to the combination of readiness and sustainability, as it has throughout the Clinton Administration.

However, modernization–generally regarded as having been neglected during the drawdown years–has moved up into the number two position, bumping force structure into third on the priority list. Defense support infrastructure comes in last.

Get Serious

“We really need to get serious about modernization,” said General Handy. “For four years, we’ve lived off savings [from] . . . quickly getting down to BUR force structure and manning levels, . . . but [the amount saved] is spent. All those resources have been reinvested.”

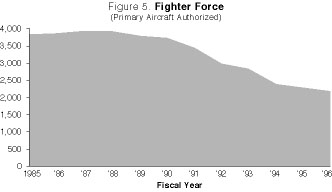

From 1985 to the present, General Handy noted, the amount that the Air Force has committed to procurement of new aircraft has fallen seventy-three percent. In a speech to the Air Force Association symposium in Dayton, Ohio, last year, he said that the service was on a “560-year replacement cycle” with regard to its fighters–a rate that he observed was “not sustainable.” This year, the Air Force budget request included money for four F-15Es and four F-16Cs. Assuming the request is approved, said the General, the replacement rate will go down to only 160 years.

“It’s a start,” he observed.

Several Congressional committees moved early in the budget cycle to add a pair of aircraft to each request. General Handy said the Air Force needs eighteen new F-15Es, which it would like to buy at a rate of six per year. The F-15E force is down to zero attrition reserve aircraft. USAF also needs 120 new F-16s to keep its wings at full strength until the arrival of the Joint Strike Fighter in 2010, but the Air Force does not know how it can afford to buy that many.

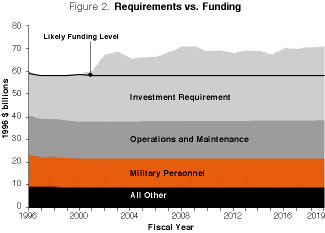

Based on current plans, the Air Force from 2001 to 2020 will fall chronically short of required spending levels, General Handy said. (See Figure 2.) There will be a $3 billion to $5 billion gap each year between stated and validated requirements and funding that the Air Force plans to request.

“Is there a bow wave [of steadily increasing unfunded requirements] lurking out there?” asked General Handy. “That always comes up, and the answer is, there is always a bow wave out past the [program objective memorandum] years. . . . Over time, you work your way through it.”

General Handy noted that some believe the Air Force has pushed requirements out beyond the current funding horizon and that it won’t be able to carry out the necessary modernization when the requirements materialize. General Handy said, however, that the trick is to decrease some of the service’s “fixed” costs so that modernization “can be afforded.”

USAF is attacking those fixed costs by aggressively seeking ways to divest itself of functions that can be more efficiently performed by the private sector, in any area where a nonorganic capability is not important to war readiness.

These measures include massive “privatization in place,” such as that proposed for the huge Air Logistic Centers at Kelly AFB, Tex., and McClellan AFB, Calif., all the way down to base support functions, such as “plumbing, refuse collection, electrical contracting, and civil engineering,” said General Handy.

Under a DoD-wide initiative, housing may be built by private contractors, then leased to the government, dispensing with many infrastructure costs associated with base housing.

Eliminating blue-suit or USAF civilian employee functions saves money by eliminating pensions, medical care, and other personnel-support costs. These funds can then be applied to USAF modernization accounts, General Handy said.

Other costs might be avoided, too, the General noted. For example, some think F-16 attrition may not occur at as high a rate as predicted, and, if so, fewer will have to be bought to keep the squadrons filled. Planned modifications may be dropped if they do not significantly add to capability or if the airplane involved is already on its way out of the inventory.

A Little More Risk

General Fogleman noted that some F-15 modifications may be eliminated, not only because the mods would cut into funds needed for the F-22 fighter program but also because the nation enjoys such a huge advantage in air superiority that “we can live with a period of risk,” he said.

General Handy noted that USAF long has observed a “five-year rule” in dealing with older aircraft. “If it’s going to be retired in five years or less, we don’t modify it,” he said.

In the case of the B-52 bomber, which has been judged to have a long service life ahead of it, “we may want to do mods,” said the General. In the case of the C-141 airlifter, now rapidly being replaced by the C-17, “we won’t bother unless there is a safety-of-flight issue.”

At AFA’s Air Warfare symposium in Orlando, Fla., last February, General Fogleman said that the capability of tomorrow’s systems may make it possible to buy fewer platforms than are fielded today. This, too, could draw the “requirements” line closer to the available budget top line, said USAF officials.

|

||

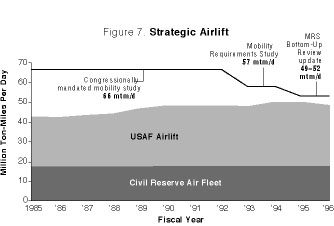

| In the post-Cold War restructuring of the US military, the Air Force shed large numbers of fighters and heavy bombers but slightly increased its long-range airlift capabilities. |  |

|

|

However, in expanding on those remarks before the Senate Armed Services Committee, the Chief of Staff said it is possible that USAF’s future “peacetime” operations–participation in multiple regional contingencies, enforcement of “no-fly” zones, and the like–may not permit the Air Force to carry out a one-for-many replacement scheme and may prove to be more taxing than the more conventional “warfighting” operations.

“I can’t definitively tell you . . . I’m going to need more or less air-superiority squadrons in the future than I need today,” the General told the Senate panel, though he added, “Intuitively, I think it will be less.”

Lt. Gen. George K. Muellner, principal deputy assistant secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, told the Military Research and Development Subcommittee of the House National Security Committee that the F-22 is one of the “least concurrent” combat airplanes ever bought by the service. By that, he meant that the Air Force is not simultaneously developing and producing various systems with a high degree of risk.

He added that, because of the lack of concurrency in the program, seventy to eighty percent of the required F-22 fixes are to be completed before the end of the current development, test, and evaluation phase. The first developmental F-22 is to fly in May 1997.

The Air Force’s Fiscal 1997 budget request for the new F-22 stealth fighter remains based on a schedule for replacing F-15s one-for-one, leading to deployment of 438 F-22s by 2010. That would provide enough fighters for four F-22 wings with adequate reserve, attrition, training, and maintenance aircraft.

General Fogleman told the Senate panel that the Air Force plans to provide special operations forces fifty CV-22 tiltrotor aircraft, which “we forecast . . . will be able to replace eighty or so airframes, . . . a combination of helicopters and tankers needed to get them the additional range.”

General Handy said that, to find savings to put into modernization, “the big money . . . is in base closures.” Of the total DoD base realignment and closure savings expected through 1990, the Air Force will have yielded seventy-one percent, or $4.7 billion, of DoD’s $6.6 billion.

“We are constantly fighting the tooth-to-tail ratio,” said General Handy. “We feel that we’re getting it sensibly balanced.”

Officials note that, since 1988, the Air Force’s spending on operations and support–including infrastructure–declined by twenty-eight percent, but spending on modernization dropped sixty-six percent.

Acquisition Reform

The Air Force is counting on acquisition reforms to help reduce some of the traditional costs–and time involved–in buying new systems. It is an area that so far has yielded nearly $3 billion in savings, but it is difficult to quantify or predict how much the reforms can save in the long run, General Handy acknowledged.

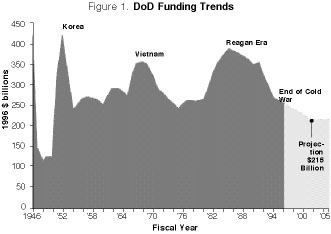

General Handy said his office, taking “an average of predictions from many sources,” anticipates that military budgets will level off at about $215 billion annually (in today’s dollars) by 2005. (See Figure 1.) If the predictions come true, it will mean “a lot less funding in our future,” he said, and will make further consolidation of service functions even more critical.

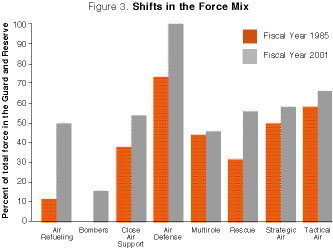

The future Air Force may have an even larger role for the Guard and Reserve. One scenario reviewed in Air University’s “Air Force 2025” study is the possibility of putting ten of USAF’s twenty FWEs into the reserve component–three more than exist there today.

“I can’t think of any area where we are not divesting substantially to the Guard and Reserve,” General Handy said.

He noted that since 1985, the Guard and Reserve have taken over all of the CONUS air defense mission and half the air refueling mission (up from one-eighth). The Guard and Reserve have more than half of the search-and-rescue capability, more than half of the close air support function, and two-thirds of all tactical forces in USAF. (See Figure 3, p. 22.)

The Air Force projects that it will spend $22.7 billion on mobility forces over the course of the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP). The mobility program includes not only the C-17 but a KC-135 modification that permits a two-person crew to fly the airplane; purchase of the C-130J and its conversion to “special mission” configurations; improvement of the C-5’s high-pressure turbine; procurement of a new “VCX” executive transport; and purchase of defensive systems for all airlift aircraft. Integration of GPS capability is not included in the FYDP but may be added later.

Because it offers greater range, altitude, and endurance than earlier types of C-130s, the J model will be used to take on the Compass Call, Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center, and other special-mission configurations.

A new “tactical requirements study” due out this summer likely will conclude that the Air Force needs fewer C-130s than it now operates, General Fogleman said, meaning it will be possible to move toward an all-C-130H tactical airlift force. This, in turn, will buy the time needed to equip special-mission units with C-130Js.

Another key feature of the Air Force program is the developmental Airborne Laser. The ABL, mounted in the nose of a 747, will enable USAF to shoot down ballistic missiles in their boost phase over the launch nation’s territory.

“I really believe the ABL will be to directed energy what the F-117 has been to stealth,” General Fogleman said. “It costs $1,000 a shot, and you get forty shots.”

General Fogleman noted that the idea has not yet been greeted with much enthusiasm outside the Air Force, so “for the foreseeable future, we’re just going to have to suck it up” and fund the system single-handedly.

Still, General Fogleman believes it will have an enormous payoff, and “then everyone will get on the bandwagon.”

General Handy reported that the lack of a modern short-range, heat-seeking missile is the most glaring problem in the air-superiority field. The current AIM-9X program is “hotly discussed.” The service has concerns that the program will not be able to deliver the needed capability in the time allotted and within available funding. Industry and defense officials said the program may be dropped in favor of a partnership with the European Advanced Short-Range Air-to-Air Missile or the Israeli Python weapon.

The “precision employment” category comprises the greatest number of new programs, including the Joint Standoff Weapon, Sensor-Fuzed Weapon, and Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM), which is the successor to the canceled Triservice Standoff Attack Missile (TSSAM). General Muellner told the House National Security Committee that USAF expects the JASSM to cost $400,000 to $700,000 per copy, as opposed to $2 million for each TSSAM round.

Precision employment activities will consume about $15.7 billion of the Air Force’s budget over the FYDP.

The new precision munitions have “very little to do with what that term meant in Vietnam,” General Handy said. Compared to the older weapons, these new systems have far greater accuracy and autonomy and greatly increased reliability and effectiveness, which, the General said, puts them in “a different category” from the 1960s- and 1970s-vintage weapons. The combination of platforms and weapons will give USAF an unprecedented level of accuracy in hitting targets.

Family Resemblance

General Handy also said that the Air Force is “very satisfied” with the progress to date on the Joint Strike Fighter program. Soon, two of the three competing teams will be selected to move ahead with the project, and one will be dropped. Many have expressed misgivings about the project, which is expected to use common engines and avionics to bring forth a family of stealthy, inexpensive combat aircraft for the Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps, and the UK’s Royal Navy. The program is now fully funded and has the full support of the Air Force, he said.

The Air Force is not seeking money to buy more B-2s or to keep the production line warm. However, President Clinton directed that the $493 million appropriated by Congress for the B-2 last year be applied to converting the first test aircraft–AV-1–into a full-up Block 30 airplane. Asked by lawmakers if the conversion would keep the B-2 production line warm, General Muellner answered, “In part.” He explained that the problem is holding the vendor base together over a longer term. The single retrofit operation “does not deal with the vendors’ issues because it is only one more aircraft,” he said.

Space systems will command $21.8 billion of USAF’s FYDP funding. General Handy said, “If this were a stock, I’d say, ‘Buy.'”

The space-systems element–including the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle, Milstar, satellite communications, and Spacebased Infrared–“gets better and better because you’re not holding on to older systems for long periods,” the General said. “It’s bound to be an area we invest more in,” he added. “We hope to transition over time to cheaper launch capabilities [and] . . . smaller, more capable payloads . . . with a fair amount of reliance on commercial augmentation.”

The information-dominance area will get $7.53 billion over the FYDP. In this respect, the Air Force asked Congress to look seriously at adding two E-8 Joint STARS aircraft to the FY 1997 program but did not include them in the formal budget request, General Handy said. The move would be undertaken to speed up the introduction of the E-8s into the inventory. The airplanes would come off the “back end” of the buy and not be an increase to the overall program.

“It would be valuable to get an additional capability into the field sooner,” said General Handy. “They have done an incredible job in Bosnia[-Hercegovina].” He added that every theater commander wants to be able to get one on short notice.

USAF’s trainer fleet has entered a period of major recapitalization. The Air Force has taken delivery on dozens of T-1A Jayhawk tanker/transport trainers and T-3A Firefly flight screener aircraft and is about to start ramping up production of the Joint Primary Aircraft Training System (JPATS).

General Handy said the T-1A “really does feel like a much bigger aircraft” and noted that the JPATS “has saved, and will save us, a lot of money.” A little more than $1 billion is in the training program through the FYDP, which includes JPATS and upgrading the T-38 Talon with avionics that will make it more similar to current front-line airplanes.