Atthe end of 2008, the average age of Air Force aircraft, in total, was exactly 23.1 years. That’s bad enough, but there is another story within that story. It is even worse.

At the same moment, the average for aircraft within the Air National Guard was 26.5 years. Within Air Force Reserve Command, the average aircraft age was 27.7 years.

|

KC-135Rs of the 128th Air Refueling Wing, Wisconsin ANG, lined up on the flight line. Aged Guard and Reserve air fleets are in need of replacement. |

The fighter forces put the age problem into even higher relief. Air Force F-16s, taken as a whole, average about 17 years of age. In the Guard and Reserve, they average more than 20 years. Air Guard F-15s, specifically, average more than 28 years of age, and those have been used in combat for some 20 years.

Plainly, the Air Force’s Guard and Reserve components need aircraft recapitalization. However, budget plans unveiled April 6 make it likely that the long-deferred modernization of the Air Force will be delayed and stretched out yet again.

Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates recommended most USAF aircraft replacement programs either be postponed or terminated. He announced that more than three wings’ worth of current Air Force F-15s, F-16s, and A-10s—a total of some 250 fighters—would be rapidly retired.

It is not yet certain what these moves will mean for the Guard and Reserve. Traditionally these components have received older aircraft as the active duty force traded up to newer equipment. However, the inventories of both the active duty and the Guard and Reserve are now old at the same time, and they will reach—and surpass—their normal retirement ages together.

US Northern Command chief Gen. Victor E. Renuart Jr. told the Senate Armed Services Committee in March that “legacy fighters” that now carry out the air sovereignty mission “will be stressed to maintain reliability and capability as we move into the 2013 to 2025 time frame.”

He said North American Aerospace Defense Command’s ability to do its job will be affected if “legacy fighters retire without a designated replacement being fielded in adequate numbers to maintain NORAD’s air defense response capability.” He said replacing these aircraft—as well as tankers and airborne warning aircraft—is critical to the future success of the NORAD mission set.

The leaders of the Guard and Reserve could not comment, in mid-April, about what solutions are in store for their aging aircraft situation. However, what does seem clear is that the three Air Force components will be sharing equipment more than ever before.

The Guard and Reserve will participate in virtually every mission the Air Force performs, and indications are they will have to continue to be an operational—and not just strategic—air reserve force. In any case, the Guard and Reserve will have to evolve.

|

Rick Mitchell of the 442nd Fighter Wing, an Air Force Reserve unit from Whiteman AFB, Mo., prepares for a nighttime sortie over Afghanistan. |

Geezer Aircraft Acceleration

Lt. Gen. Harry M. Wyatt III, head of the Air National Guard, sees trouble from the phaseout of 250 fighters from the combined force. If they come mostly from the Air Guard, he said, it will leave much of the air sovereignty mission unmet.

About 80 percent of the Guard’s 460 F-16s are performing that air sovereignty mission, which entails tracking, challenging, and intercepting suspicious or unresponsive aircraft entering US airspace. It’s a mission that must be performed, Wyatt said, but there’s no consensus on what the Guard will use to do it.

The retirements would “accelerate” the Guard’s old aircraft problem, which is already growing acute, he said.

The Government Accountability Office recently sounded an alarm about this. It said in a January report that the alert mission could be without viable aircraft by 2020 unless someone quickly takes steps to replace old F-15s and F-16s. The watchdog agency said the Air Force hasn’t dealt with the issue yet because it’s been “focused on other priorities.”

Under plans set in motion even before Gates’ April announcements, most strip alert sites that currently support the air sovereignty mission will have retired their airplanes between 2010 and 2020, the GAO said. By 2022, half the Guard’s fighter units will have no aircraft. With no replacements, the Guard by 2026 will have retired all its F-16s.

This is not strictly a hardware problem. Wyatt noted that today’s Air Guard pilots are among “the most capable, combat-experienced crews that we’ve had in years,” thanks to nonstop real-world combat deployments since 1990. If “they don’t have anything to fly, then you lose that capability,” Wyatt asserted.

The ANG chief added, “It’s not just a money decision. It’s not just a capability decision for today—it’s one that could affect us for a long, long time, because it would take generations to replace” the combat experience that would be lost. The fighter mission may not have much direct use to state governors, for whom the Guard also works, but it is crucial for the strategic capabilities of the nation, he said.

So strongly does Wyatt feel about the need to recapitalize the Guard with new fighters that he thinks the ANG should get priority over Pacific Air Forces and US Air Forces in Europe in being provided with new-build F-35s. He believes that despite urgent pleas from the PACAF commander, Gen. Carrol H. Chandler, and the USAFE commander, Gen. Roger A. Brady, for the Air Force to provide F-35s in those theaters first.

|

Capt. Susan McCormick, a Reservist from Westover ARB, Mass., inventories supplies on an aeromedical evacuation flight en route to Manas, Kyrgyzstan. |

“Certainly, I can’t deny the importance of their missions,” Wyatt said, “but what I think we need to do is, while we recognize the importance of USAFE and PACAF, the fight that we cannot lose is the one that takes place over the continental United States.” Forward theater commanders usually have “the luxury” of determining the time and place and equipment they will use in an air action, whereas the CONUS defenders don’t, Wyatt asserted.

“We really, no kidding, have to have a discussion about the No. 1 mission, in my mind, which is defense of the country,” he said. “The Air Force needs to make some decisions about what missions they can afford to take risk in, and which ones they can’t.”

Wyatt added, “I think the No. 1 mission needs to be given the No. 1 priority, and the best airplane available to do that.”

Gen. Craig R. McKinley, head of the National Guard Bureau, said in February that the Air Guard would have to be “proportionally resourced” to the active force in fighters. He told reporters in Washington that meetings were under way with Air Combat Command to make the allocations. The apportionments would have to harmonize with the overall question of deciding “how many fighters we need in our Air Force.”

Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.), chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, said in March he recognizes the punishing load the Air Guard has borne. Speaking with reporters in Washington, he said the Air Guard has been “clearly … overused” by way of providing additional manpower and equipment over nearly two decades of operations.

“If for whatever reason a decision is made to continue to rely on [the Air Guard] to the extent we have, then we’ve got to provide it with the equipment that has been a necessary part of that use,” Levin said. “It’s got to be recapitalized.”

Wyatt said the Air Guard may be in for some serious rethinking, due to the greater use it’s seen, as well as the need to replace its worn-out equipment.

Funding of the Air Guard “is still heavily influenced by the Cold War,” he said.

The ANG participates in air expeditionary forces, performs the air sovereignty mission, supports state governments at need, and continues to be the strategic reserve of the Air Force. Yet, despite being an “operational force,” Wyatt said, “we’re still funded like we were nothing more than the old strategic reserve of the 1960s and 1970s. And so we need to take a look at the way we resource and fund the Air National Guard.”

If homeland security “is really mission No. 1, then let’s put our money and our resources where our mouth is. … That’s what I think we need to do.”

|

A Wyoming Air Guard C-130 is readied for a mission at Balad AB, Iraq. |

In testimony before the Senate Appropriations defense subcommittee in March, Wyatt said he has “not ruled … out” the possibility that the Guard could meet its equipment needs by buying new examples of the F-15 and F-16. The Air Force has long said it doesn’t want to buy “new old” fighters and is committed to a fifth generation fighter force.

Preserving Options

However, members of Congress have pointed out that it is hard to significantly speed up the F-35 program—a great deal of the test program has yet to be performed—while the F-15 and F-16 are still in low-rate production for foreign customers.

Wyatt told the panel that progress has been made in earmarking some early F-35s for the Guard, but “we are preserving our options to include a fourth generation buy.”

Wyatt’s counterpart at the Air Force Reserve, Lt. Gen. Charles E. Stenner Jr., said in an interview with Inside the Air Force that he opposed buying new fourth generation fighters. They would have to be supported over a 30-year life expectancy—an unwanted and potentially large expense.

Moreover, Stenner said, the aircraft would be progressively less relevant against adversary defenses, which will pose serious challenges even to fifth generation fighters. Buying new F-16s or F-15s would “perpetuate the problem,” Stenner said.

Rethinking the Guard is something that will likely flow from new US strategic documents, Wyatt said. Moreover, regional combat commanders will have a say.

“I would just remind everybody,” said Wyatt, “that there is a combatant commander called NORTHCOM, who … should be considered just as seriously as any other combatant commander around the world. And I’m not so sure that [NORTHCOM] is getting the attention it deserves.”

The elevation of McKinley to National Guard Bureau director with four-star rank means the Guard will now have a seat at the table where the overarching decisions are reached, Wyatt said. The Air Force will bring its views, and the Quadrennial Defense Review will play a pivotal role in deciding the Guard’s future, he said.

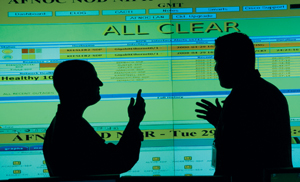

|

Cyber-war is seen as a key mission for the Guard and Reserve; civilian experts are expected to lend their network defense skills to USAF. |

Although the Guard has traditionally been an “airframe-based” organization, “we need to think about capabilities,” Wyatt said.

The Guard is a natural place to invest in cyber capabilities, Wyatt said, because it can draw on information industry experts with a desire to serve their country. The Air Force can’t compete with the industry on pay and benefits, but needs the expertise, and the Guard is one way to get it.

He also sees “dual use” capabilities as a new growth area for the Guard, particularly in platforms such as unmanned air vehicles and intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance systems. In those systems, the equipment can serve the state role in an emergency as well as the federal role as part of the Total Force.

The Guard will likely play a big role, he said, ranging from operation of UAVs to exploitation and dissemination of ISR products, a field that is slated to receive a boost in funding and manpower both. Moreover, the Guard can play in soft power operations such as training of foreign militaries—a role for which Wyatt thinks it is especially capable.

“It’s not just about delivering kinetic effects,” he said. “It’s about delivering effects, and you can do that in a lot of different ways,” he said.

Though the Guard’s size is about one-third that of the active force—106,700 airmen, compared to 327,000—he doesn’t expect a proportionate share of the budget. Still, tighter budget times and a smaller fleet mean that, more than ever, the Air Force and the Air Guard must be “co-equal” partners, according to the ANG director.

Embedded Associates

The ANG “should be involved in the same capabilities and the same platforms” as the active force, he said. In the past, when the Air Guard’s functions “were not mirrored” in the regular force, they tended not to be given sufficient resources. That won’t work anymore, Wyatt said.

Although the missions of the Air Force demand about a half-million-person force, “we cannot afford to have 450,000 active duty airmen,” and the Guard—and Air Force Reserve—make up the difference in the most cost-effective way possible, Wyatt asserted.

The Air Force will soon be experimenting with something called “embedded associates.” There are three kinds of unit associations now. In a Guard or Reserve associate arrangement, personnel from the Guard and Reserve are hosted by an active unit and use its equipment. In an active association (once called a reverse associate arrangement), active duty personnel are hosted by a Guard or Reserve unit and use its equipment. In a reserve associate unit, Guard and Reserve members work with each other.

|

Lt. Gen. Harry Wyatt III (r), head of the Air Guard, makes a point at a Congressional hearing. Wyatt thinks homeland defense should be among the first missions in line for new F-35s. To his right is Vice Adm. Dirk Debbink, chief of the Navy Reserve. (USAF photo by TSgt. Amaani Lyle) |

The embedded associate concept won’t work like the others, and there will be no template to follow, Wyatt said. On a unit-by-unit basis, force structure and manning will be evaluated to see how more capability can be squeezed out of assets already on hand. The percentages of active, Guard, and Reserve billets will vary from unit to unit.

Manning levels won’t change, but the idea is to get maximum use out of assets that might otherwise remain idle—for example, during a weekend, in the case of some active units—so that utilization rates go up.

The approach is not to reduce costs—manning levels won’t change—but to increase the capability and the manpower available, Wyatt said.

The embedded associate is the first step in what Secretary of the Air Force Michael B. Donley has termed “Total Force Integration II.”

After the last round of base realignment and closure, it was necessary to shift some people and missions, “to help facilitate the good things that came out of BRAC but also mitigate some of the ‘broken glass’” that came out of it, Wyatt said. Now, Donley wants to know “have we done all we can with TFI?”

After discussions involving Wyatt, Stenner, Donley, and Chief of Staff Gen. Norton A. Schwartz, “the consensus was that it’s going to be hard work, but there are some opportunities that remain” in homogenizing the three components, “and we need to keep calling it TFI,” Wyatt reported.

There are “great opportunities” for further associations and partnerships, he said, particularly in cyber, ISR, and UAVs. The cyber mission is being developed from the beginning with the Guard and Reserve components and the active force. Also, the Guard is slated to receive a new airlift system, the C-27J transport, which is smaller than the C-130 that has been a staple of Guard missions for decades.

Even in the nuclear mission, Wyatt sees opportunities. He noted that Air Guardsmen are flying B-2 bombers, perform security for nuclear sites at Minot AFB, N.D., and sit strategic alert in KC-135 tankers. The Guard is being incorporated into the Personnel Reliability Program, which vets airmen’s stability and trustworthiness for work with nuclear systems.

“Secretary Donley asked me to consider all possibilities, not to be constrained by any preconceived notions that any career field was off-limits,” Wyatt said. “He specifically mentioned ICBMs.” He added, “I can see some circumstances where that might work. And we’re looking at those.”

A few years ago, Wyatt said, then-Chief of Staff Gen. T. Michael Moseley, now retired, ordered a study to see what the Air Force would look like “if you threw away all the preconceived notions of what [it should look like] and how it should be constructed. … The answer that came back [was], … it looked a whole lot like the Air National Guard with active associate members bedded down in the Reserve units.”

The study found that the Guard and Reserve offered “the most efficient way of doing business … [at the least] cost to the taxpayer,” Wyatt asserted. “You pay for the military capability you need at the time; you don’t pay for a large standing military.”

Stenner, chief of the Air Force Reserve, said the fiscal situation clearly means there needs to be some rebalancing of the relative weights and roles of the active, Guard, and Reserve elements.

“We know that there are new mission areas that we’re likely to be involved in because we are … involved in everything the Air Force’s three components do,” Stenner said. Like the Guard, he said the Reserve will be involved more with UAV, cyber, nuclear, and ISR missions. However, he cautioned that the latter poses some problems because ISR is already so heavily tasked, and the Reserve recruits mainly from active personnel who are leaving.

“We have less of an ability to recruit when we have a highly stressed, LD/HD [low-density, high-demand] career field. Folks who are leaving the regular Air Force know that we are just as much ‘all in’ in the Reserve and Guard. So, they hesitate to come on board with us when they leave.”

|

SrA. Fred Egan, a Reserve avionics technician from Indiana, checks tools while deployed in Southwest Asia. Leaders say Reservists need flexibility in overseas deployments. |

The Reserve Triad

Stenner said the key to preserving the Reserve will be to keep active duty periods both predictable and flexible. Reserve people can’t keep being mobilized and not have it affect their families and employers, the two other legs of what he called “the Reserve triad” that allow the organization to function. Without the home support, there’s no Reservist.

While the ideal continues to be a 120-day deployment every five cycles of the Air and Space Expeditionary Force, “we know that’s not reality right now,” Stenner said, and “dwell” times of one-to-three, one-to-two, and even one-to-one are not unknown in the Reserve.

“I can be more ‘in’ in certain areas, but [it] will have an impact,” he said. If Reservists are needed, he said, the Reserve won’t hold back. However, if the mobilizations continue to be the rule, and “if we continue to use that asset over and over and over, then they’ll leave us.” The key will be maintaining the predictability—even if it is frequent—and the flexibility to break up deployments in chunks easier for Reservists to manage. Stenner said he needs the flexibility to convert a single-person deployment of 120 days into a deployment of three or four people for 30 to 40 days apiece.

Stenner warned that “if we are firm in our belief that 179 [days deployed] must be for everybody, then there will be folks who just cannot do that.”

However, he noted that “interestingly, what we are finding … is, the folks who are deploying have a higher retention rate than those folks who haven’t deployed. That’s telling me that those folks … want to do what they’re trained to do and do want to serve their country.”

Is comparability of pay and benefits an issue

“We have made tremendous strides,” Stenner said. Of 29 benefits offered to active, Guard, and Reserve members, “25 of those are exactly the same. … The other four are slightly different, and in most cases, for good reason.” He added that in polling of Guard and Reserve members, “there were small nuances to those benefits, but … we have not heard of those being major detractors” from serving in the Guard and Reserve.

Stenner and Wyatt both said that it will be important to preserve the culture of their organizations even as they become more integrated with the active Air Force. Leadership of highly mixed units was predicted to be a problem, but really hasn’t turned out to be one, they said.

Stenner noted that “operational direction” in associated units “on any given day, is done by memorandum of agreement.” Generally, he said, “he who has primary responsibility for the mission” is in charge.

“On a daily basis, they’re working for whomever owns the iron,” he said.

Wyatt would like to see greater recognition given to those Guard and Reserve members who have developed special skills and have leadership roles in their civilian lives, which he hopes will make them more competitive for command assignments in the future.

So, what’s next for Total Force

It’s “to look at every new mission area through the lens of association,” Stenner said. “And to look at how we best balance the active … and the Reserve component—how we best balance the full time and part time to give you the daily capability we need around the world.”

Wyatt said, “I would hope that our leadership … will take an honest look at ways to enhance the defense of this country by a Total Force approach” that would consider the “unique capabilities” of the Air National Guard, “and I really think they will.”