All eyes will be on the Government Accountability Office this month as it decides whether the Air Force properly awarded the KC-X aerial tanker contract to Northrop Grumman, or if Boeing, which lost the contest, has good reason to claim its offer wasn’t treated fairly.

The Air Force on Feb. 29 selected Northrop Grumman-EADS North America’s KC-30 aircraft design over Boeing’s KC-767 in the huge, multibillion-dollar KC-X contest. Boeing almost immediately protested, throwing the matter before the GAO—the designated arbiter of federal contract disputes.

However it goes, the GAO decision, expected midmonth, will have big implications.

If the Air Force’s choice is upheld, it can finally get on with building new, urgently needed airplanes. If not, the tanker replacement process—already a controversial, seven-year odyssey—could stretch out another three years or more, forcing flight and ground crews to wait that much longer to trade in their 1950s-era KC-135Es for fresh aircraft.

|

Left: A Northrop Grumman artist’s conception of the KC-30. Right: A Boeing illustration of the KC-767. The two images are drawn to the same scale. |

The financial, political, and military stakes in the tanker contest could hardly be higher, and certainly go well beyond the gargantuan $35 billion to $40 billion value of the contract. Thousands of jobs are at stake, raising the political heat in Congress, and even affecting this year’s Presidential campaign. Because half of the money that would go to Northrop Grumman will pass to European Aeronautic Defense and Space Co., whose Airbus A330 is the basis for the team’s winning KC-30 entrant, the tanker has become a cause célèbre for protectionist interests. It has made strange bedfellows of conservatives and labor unions that charge that the Air Force is paying to send good jobs and taxpayer dollars overseas.

Whoever had won, a protest by the loser was seen as virtually inevitable. The contract is so large—up to 179 airplanes—that it could have a significant impact on airliner market share. That, and the fact that big military airplane contracts are becoming rarer, made the KC-X a must-win for both contenders.

It took Boeing little more than a week to file its protest. In March, the Air Force and Northrop Grumman separately petitioned GAO to summarily dismiss the action, but on April 2, the GAO refused, saying it did not think doing so would be “appropriate.” The GAO has 100 days, by law, to make a finding.

The Air Force’s credibility is on the line in the tanker procurement. The service’s original plan, to lease tankers from Boeing, blew up when it was discovered that Darleen A. Druyun, a top USAF acquisition official, had secretly been doing contractual favors for Boeing, some of which involved the lease.

Then came the combat search and rescue helicopter contract. The Air Force picked Boeing to build the CSAR-X in late 2006, but losing competitors successfully argued to the GAO that the service had failed to follow its own rules in making the choice. The contract was set aside, and the CSAR-X went back into competition.

With two strikes against it, the Air Force has bent over backward to ensure that the tanker contest would be as problem-free as possible, according to Sue C. Payton, the service’s acquisition executive. If that turns out not to be the case, though, the Air Force’s ability to run a big acquisition properly will be in question.

|

A KC-767 refuels a B-52. (Photo by Boeing) |

The KC-X program, the third-largest contract in USAF history (after the F-22 and C-17) is also likely to be worth more than face value. The service has long said that, just as the KC-135 platform was adapted for other large special mission aircraft such as the AWACS, Joint STARS, and Rivet Joint, so too does it expect that the KC-X will be the basis for replacing those KC-135-derived airplanes. Indeed, the E-10 Multisensor Command and Control Aircraft, the planned successor to both the AWACS and Joint STARS, was to be a Boeing 767, largely because that platform was also expected to be the tanker. The E-10 program has since been canceled due to tight money, but the requirement persists.

All told, industry analysts peg the cost to replace the large special mission aircraft at a minimum of $10 billion, and probably much more.

In addition, the KC-X is merely the first installment of replacing the tanker fleet. The first batch of tankers to be replaced are the oldest, the KC-135Es, which have flight restrictions and serious problems with landing gear struts. A KC-Y competition, circa 2020, will replace the KC-135Rs, which were converted from KC-135Es by adding newer engines and some structural improvements to extend their lives. About 10 years after that, USAF envisions a KC-Z contest, meant to provide a successor to the KC-10.

Even if this schedule plays out just as the Air Force intends, some KC-135s will be serving beyond their 80th year, something skeptics think just won’t be possible.

Although the Air Force has said it will look afresh at its tanker needs in each of those competitions, it has also said it wants to minimize the number of different airplanes in its fleet, to keep commonality up and training and logistics costs down. That means the winner of KC-X has a leg up on any comers for the second two matches.

The tanker outcome will also influence several ongoing studies of mobility capabilities and requirements, all due within the next year. Since the KC-30 is so large, its capacity could well affect how many additional C-17s and C-130s the Air Force will be allowed to buy. Some senior service officials have expressed a concern that, because of its size, the aircraft could be counted twice—once as a tanker and once as a cargo airplane—and wind up shortchanging both elements of the mobility portfolio.

In announcing Northrop Grumman as the winner, Secretary of the Air Force Michael W. Wynne said the new airplane will “have the flexibility to perform additional taskings, including carrying cargo, passengers, and air medical patients.” Speaking at a Pentagon press conference, Wynne said Air Force evaluators “took the time to gain a thorough understanding of each proposal. They provided continuous feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of each proposal, and they gave the offerors insight into the Air Force’s evaluation.”

However, the Air Force offered little explanation as to why it chose the KC-30. (The ultimate winning aircraft will be designated KC-45A.)

|

A Northrop Grumman illustration of a KC-30 refueling a C-17. (Northrop Grumman illustration) |

Payton, asked to explain the choice, said at the press conference that “we had two very competitive offers in this competition. Northrop Grumman clearly provided the best value to the government” in light of the top five considerations. In order of importance, they were: mission capability, proposal risk, past performance, cost/price, and “something we call an integrated fleet aerial refueling rating.”

She said Northrop Grumman’s team “did have strong areas in aerial refueling and in airlift,” adding that “their past performance was excellent, and they offered great advantage to the government in cost/price, and they had an excellent integrated fleet aerial refueling rating.”

The KC-30 is slightly larger than the KC-10, and twice the size of the KC-135E it would replace. It would offer substantially more fuel and cargo capacity than Boeing’s KC-767. It can also pump gas into a receiving aircraft somewhat faster than can the KC-767, and has been ordered by Britain, Australia, and Saudi Arabia. Northrop Grumman said that, if it won the contest, it would perform final assembly of the aircraft in Mobile, Ala. Airbus also said that a win in the tanker contest might persuade it to build its commercial A330s in Alabama as well. No such facility exists yet; Airbus said it would only build if it won the KC-X.

Tremendous Peer Review

Payton declined to offer any further details about why the KC-30 bested the KC-767, saying that USAF owed that information to Boeing first. Once Boeing protested the award, however, the Air Force said it couldn’t discuss its reasons until the GAO made its findings known.

Payton insisted that the two offerors knew “exactly where they have stood all along in all of the various factors, as we were evaluating them.” She said the Air Force has had the Pentagon inspector general, as well as the GAO, review its processes “and take a look at all of our audit trail” from setting requirements through the request for proposals. There has been “tremendous peer review” by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and the selection team included acquisition experts from the Army and Navy, she said.

“We’ve had a very thorough review of what we’re doing,” Payton asserted. “The Darleen Druyun situation was a half a decade ago,” and the Air Force this time had scrupulously followed federal regulations. She added, “We’ve got it nailed. … There was absolutely no bias in this award.”

Boeing, however, saw it differently.

In its protest documents, Boeing charged that the choice of Northrop Grumman’s entry was a surprise because it seemed obvious that the Air Force didn’t want such a large airplane. The service was, after all, replacing the KC-135E tanker and not the much larger KC-10 refueler.

So clear did this seem that Boeing had held a press conference early in the competition to announce that it had discarded its KC-30-sized KC-777 proposal because it saw no competitive advantages for a larger airplane, and didn’t want the Air Force to carry around weight it doesn’t need.

In its protest, Boeing argued that, in any competition, the source selectors assess two levels of capability. The first is the “threshold,” which is the minimum performance required and which the contractor must meet in order to bid. The second is the “objective,” which is performance that the service deems nice to have, but not essential. Performance up to the objective is encouraged, but usually not beyond, because providing unneeded capability risks “gold plating” the system, Boeing Vice President Mark McGraw told reporters.

Speaking in a teleconference in April, McGraw said that, in his last meeting with KC-X evaluators, he sought clarification on the size issue.

McGraw reported having asked, “We’ve gotten the maximum we can? You can’t get any more credit for going above the objective, right?”

The answer, McGraw said, came back, “Right. There is no credit for exceeding an objective.”

|

Rep. Norman Dicks (D-Wash.), a staunch Boeing supporter, addresses a Capitol Hill rally against the contract award. (AP photo by Jose Luis Magana) |

After being debriefed by the Air Force, McGraw said, Boeing believed the service, in fact, “gave credit to the competitor [Northrop Grumman] for going above the objective in several areas. And that is one of the key points of our protest.”

If Boeing was listening to senior serving generals, its notions about size were probably reinforced. Privately, top USAF officers frequently said they were looking for an ability to put many tankers on forward runways at once, since strike packages involve many airplanes, and each tanker can only refuel one other boom-receptacle airplane at a time. (Both the KC-30 and KC-767 can simultaneously refuel two other aircraft if the receiving airplanes are equipped with probe-and-drogue type refueling gear). However, those generals were quick to point out that they had no say in the acquisition process, and the outcome of the competition bore that out.

The integrated fleet aerial refueling (IFAR) evaluation was a computer model which gamed each tanker against a set of real-world conditions involving a variety of scenarios, assumptions about basing availability, fuel offload, cargo-carrying capacity, ground turn time, etc. Boeing contended that, near the end of the competition, the Air Force relaxed some of its standards, which gave an unfair edge to Northrop Grumman.

For example, the minimum spacing between aircraft on a forward ramp was reduced from 50 feet to 25 feet. That allowed more KC-30s to fit in some places, Boeing said. Boeing also charged that the Air Force allowed some nonexistent forward runways to count in the model. Moreover, the company maintained that its airplane would be cheaper to operate, since it was smaller than the KC-30 and would burn less fuel.

Unequal Scrutiny

Boeing further observed that its own cost numbers were not accepted by the Air Force, which substituted higher numbers because the service did not find Boeing’s figures credible. At the same time, Boeing claimed, Northrop Grumman’s numbers were not subjected to the same scrutiny.

In April testimony before a House Armed Services subcommittee, Payton explained that the changes were made to make the computer model “more realistic.” The head of Air Mobility Command, Gen. Arthur J. Lichte, told the panel that wingtip-to-wingtip clearance was reduced because, although it is 50 feet in peacetime, “in wartime—and what we’re using today—it’s 25-foot wingtip clearance. So we decided that’s what we should [use].”

Boeing also said that the IFAR model was developed by Northrop Grumman and that the firm had special insight into how the model worked. Northrop Grumman acknowledged that, but noted that the model has been used for years, and insisted there were strict firewalls in place between the division that developed the model and its tanker team.

The original list of Boeing’s complaints required 138 printed pages, and four supplements were submitted to the GAO as the company discovered more problems, McGraw told reporters in early April. He speculated that when Northrop Grumman threatened to quit the competition if certain metrics weren’t adjusted to make it more competitive, the Air Force probably went too far in trying to accommodate it. The company said that the final scorecard between the two entrants was extremely close, and that if its price and other factors had been rated fairly, Boeing should have won.

|

Sen. Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), at right, backs Northrop Grumman in the dispute. Seated next to Shelby is Sen. Chris Dodd (D-Conn.). (AP photo by Susan Walsh) |

Northrop Grumman, in subsequent weeks, issued scores of press releases portraying Boeing’s case as little more than sour grapes and “disinformation.” It noted that Boeing was late delivering KC-767s to Italy and Japan, and that Boeing had regularly touted the KC-X competition as apparently fair and problem-free.

Paul K. Meyer, Northrop Grumman’s vice president for air mobility systems, said his team never threatened to walk out on the competition, but said in a teleconference with reporters that “we utilized our right to articulate our concerns about selected criteria.” Meyer also acknowledged that, although “100 percent” of the revenues from the tanker will go to Los Angeles-based Northrop Grumman, “50 percent” of that money will go to EADS as a subcontractor. The company has said the tanker program will bring 24,000 jobs to the US, but since winning the deal has revised that figure to 48,000 jobs.

When the tanker competition first got under way, the Air Force’s solicitation to interested companies asked them to explain any subsidies they receive from their governments. The proviso reflected a long-simmering US-Europe trade dispute in which the US charges that European governments are unfairly subsidizing Airbus products in order to underbid Boeing in the airline arena and gain market share. Airbus said the subsidies have been repaid. European governments, moreover, have charged back that Boeing’s military work for the US constitutes a subsidy of its own. The argument is still pending before the World Trade Organization.

Sweetheart Deal Accusations

Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) criticized the language about subsidies as a way for the Air Force to essentially exclude any competitors other than Boeing. This was unacceptable, in his eyes, much as was the earlier lease arrangement, which he branded as being a sweetheart deal for Boeing. He wrote to Deputy Defense Secretary Gordon England, then Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates, saying a new tanker program would only fly if it resulted from “a full and open competition” free from the “capriciousness” of assessing the role of subsidies in a proposal. The subsidy language was dropped.

With Northrop Grumman’s win, McCain—now running for President—has been criticized for setting the stage for the export of the work that could have been had by Americans.

The chairman of the House Democratic Caucus, Rep. Rahm Emanuel of Illinois, said the person chiefly responsible for preventing the tanker contract from going to a US company was McCain, “and now we are going to send major high-paying jobs overseas.” Boeing’s headquarters is in Illinois.

|

Airmen unload a KC-10 at McChord AFB, Wash. (USAF photo by TSgt. Scott T. Sturkol) |

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) asserted that Boeing would have gotten the work but that “Senator McCain intervened, and now we have a situation where the contract may be … outsourced.” She added that “if we continue to outsource these contracts, we are exporting jobs out of our country. …We will not have the industrial and the technological base necessary to ensure our national security. … It will fade; it will diminish.”

Payton, in testimony before the House Appropriations defense subcommittee, said the Air Force is required by law to consider a bid from certain allied countries—much of Europe is on that list—as if it were a bid from a domestic US supplier. She also said that the KC-X contestants agreed that if the WTO makes a ruling against their country, “if there are penalties assessed on them … that they would not convey any of those losses onto the Air Force.”

Norman D. Dicks (D-Wash.), a member of the House Appropriations defense subcommittee, said on the March 6 PBS “NewsHour” that “the only reason” the Northrop Grumman team could bid low on the tanker “is because they received [a] subsidy. And you know, … Senator McCain jumped into this … and said that they could not look at the subsidy issue, which I think is a big mistake, especially when the US trade representative is bringing a case in the WTO on this very issue.”

Dicks, who represents the state where Boeing assembles the 767, said in the March 5 House Appropriations defense subcommittee hearing that “the Air Force has failed us here.” He charged that the service “changed the deal in midstream to accommodate Airbus, because … they said they would pull out of the competition if [the Air Force] didn’t do it.”

He also said the tanker is “a crown jewel of American technology. We are now giving away to the Europeans one of the most significant things we as a country can do, and that is build these aerial tankers.” Northrop Grumman said that the refueling system on its KC-30 was developed by an EADS-Sargent Fletcher team, and that no military technology transfer to Europe will occur.

At the same hearing, Rep. Todd Tiahrt (R-Kan.) said, “The American public is rightfully outraged by this decision. I am outraged by this decision. It’s outsourcing our national security. … Choosing a French tanker over an American tanker doesn’t make sense to the American people, and it doesn’t make any sense to me.” Boeing planned to modify some of the KC-767s in Tiahrt’s state.

He noted that the KC-X marked three times in a row that the latest big defense contracts have gone to European designs: the Marine One Presidential helicopter went to Lockheed Martin fronting the European EH-101; the Army light utility helicopter will be a Eurocopter design; and now the EADS KC-30 for the KC-X. He didn’t mention it, but Boeing is on the team to build the C-27J Joint Cargo Aircraft, designed in Italy.

|

A KC-135 refuels an F-16 over California. The KC-X competition is expected to be followed by competition to replace the remaining legacy tankers. (Photo by Ted Carlson) |

Why Not Buy American

“We are stacking the deck against American manufacturers at the expense of our own national and economic security,” Tiahrt asserted. He said he understood that the Air Force didn’t take industrial base considerations into account when choosing the tanker, but “Congress has made it clear over the years its intent that taxpayer dollars should be spent for American work, whenever possible.”

He went on to claim that the loss of tanker know-how in the US will result in a more vulnerable nation, and “we cannot allow this to come true. We must have an American tanker built by an American company with American workers. Congress must act to save the Air Force from itself.”

Statements from various unions, including the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, struck similar themes.

McCain’s response has been to maintain that he always wanted the Air Force to pursue the tanker as fairly as possible. His rivals for the Presidency have both questioned the choice of Northrop Grumman. Sen. Barack Obama (D-Ill.) asked how Boeing, which has been “a traditional source of aeronautic excellence, would not have done this job.” Sen. Hillary Clinton (D-N.Y.) said she was “deeply concerned” about the award, given that “our government is simultaneously suing [the European Union] at the WTO for [giving] illegal subsidies” to Airbus.

Rep. John P. Murtha (D-Pa.), head of the House Appropriations defense subcommittee, told senior USAF acquisition leaders in a March hearing that “none of us dispute the integrity” of the acquisition team, and “we have no question you did the best you could do.”

However, he added, “we’re going to do the best we can do, in evaluating this thing politically. … When I say politically, I’m talking about industrial base. … This is part of it and we have that responsibility under the Constitution.” He earlier said that “all this committee has to do is stop the money” and the tanker program is “not going to go forward.”

In a March 9 editorial for the Financial Times, Sen. Richard C. Shelby (R-Ala.) urged Congress to “remain as objective as possible and insist on due process. Invalidating the award, starting the process again, or inserting prohibitive language into legislation to block the tanker acquisition would be irresponsible and based on raw emotion.” He said that in a global economy, it’s “almost impossible” to obtain a military product that is “100 percent US-made,” and said that comparing the two tankers shows they have “a similar amount of foreign content.”

|

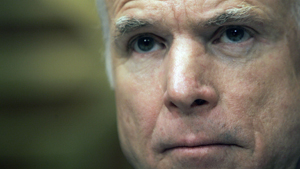

Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) offered harsh criticism of the Air Force’s original guidance to companies interested in the tanker competition. (AP photo by Mary Altaffer) |

So, what happens now? The GAO sets a very high bar in adjudicating protests of contracts. Even if it’s discovered that the Air Force did make some errors, the GAO won’t set aside the award to Northrop Grumman if it considers those errors immaterial to the outcome of the competition. In order for Boeing to get the award set aside, it must prove not only that the Air Force made mistakes or showed unfair preferences, but that those mistakes or preferences were key to the outcome of the contract.

If the GAO finds for Boeing, there are numerous remedies at its disposal, depending on the severity of the problem. It can order that some portions of the contract be re-evaluated by the Air Force, or rescored to reflect more accurate information. It can direct both offerors to resubmit certain data, or direct a change in some of the evaluation methodology or modeling. It can also throw the whole award out and tell the Air Force to start over.

If GAO allows the award to stand, Congress could still intervene, potentially directing the Air Force to split the buy between the two companies, or run competitions for each lot. During the KC-X contest, the Air Force ruled out such an approach, saying it would cost $2 billion extra up front and another $4 billion to set up a separate logistics capability for an additional tanker. Since the lots are expected to be for 15 to 18 aircraft, the Air Force said, there isn’t an economy of scale to justify two sources for the tanker.

However, if Congress does intervene and take some or all of the tanker work away from Northrop Grumman, it could have a chilling effect on prospects for sales of American-made military products or airliners on the other side of the Atlantic, worsening the aerospace trade dispute with Europe. That, in turn, could sink the chances for a NATO buy of, for example, C-17s, making that aircraft more costly for USAF to purchase.