Air Force Maj. Brian Liebenow arrived to a secret staging point at a former Soviet base in Uzbekistan on Oct. 6, 2001, for an intense mission that would last just over two months. There, as a member of the 23rd Special Tactics Squadron, he briefed the special operators flying MH-53 and Chinook missions into Afghanistan to assist in the overthrow of the Taliban.

“The Taliban were really on their heels,” Liebenow, now 46, told Air Force Magazine, his voice raspy from multiple throat surgeries and frequent intubation.

Many of those special operators are now dying of cancers and suffering from respiratory, skin, gastrointestinal, reproductive, and other disorders believed to be related to the toxic exposures they faced at the Karshi-Khanabad Air Base, known as K2, but their treatment is not covered by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The same is true for hundreds of thousands exposed to burn pits in Afghanistan and Iraq.

When non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cancer struck Liebenow in 2003, he was still serving in the Air Force, and his medical expenses were fully covered.

“I felt really lucky that I was diagnosed while I was Active duty and I got all of my treatment paid for,” Liebenow recalled after seeing a Facebook page of veterans fighting to overcome VA coverage denials.

Millions of other Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans exposed to burn pits, airborne hazards, particulate matter, and other toxins are unable to receive pre-screening tests and must pay their own medical expenses if they left the service and cannot prove their ailment is service-related. A new bill before Congress could change that.

‘An Urgent Crisis’

The Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act of 2021, an omnibus bill of 15 pieces of legislation that passed out of the House Veterans Affairs Committee in June, would require medical tests and presumption of service-related diseases so that veterans don’t have to prove their ailment was related to their service.

“We are in an urgent crisis with people, who are dying of cancer, not getting covered by the VA,” Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) said during a recent media call hosted by the Defense Writers Group.

“As a consequence, they have to use their own money and are going into bankruptcy and losing their homes and going into other financial ruin just to protect their health and well being,” she said. Another Congress is too long to wait, she said. “It has to be done this Congress, and it needs to be done as soon as possible.”

The Senate Armed Services Committee member threw her weight behind the bill, which includes parts of her own Senate bill that had been vocally endorsed by activist comedian Jon Stewart. Stewart was instrumental in getting similar legislation passed for 9/11 first responders.

“I’m excited to see if they can keep our whole legislation in this larger toxic exposure package,” Gillibrand said. “I’m optimistic with the strong bipartisan support that we have. We will get a vote on our bill, and it will pass. And I think it’ll pass in this Congress.”

The so-called PACT Act sponsored by House Veterans Affairs committee chairman Rep. Mark Takano (D-Calif.) passed out of committee in June and now has 35 co-sponsors.

“Chairman Takano has made this a priority,” an HVAC staffer told Air Force Magazine, citing the chairman’s commitment and success in passing the Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019.

“There’s a presumptive condition determination process that’s being revamped that will incorporate a science review board,” another staffer explained, noting the entire VA process will be accelerated. “We would force their hand if the legislation passes the House and Senate and is signed by the President.”

But a looming problem remains, which has sunk all previous bills and staffers declined to discuss: cost.

‘A Family Tradition’

Liebenow came from a military family. His sister was an officer in the Army. His dad served six years and two tours in Vietnam as a Marine. And his grandfather, William ‘Bud’ Liebenow, was a naval officer during World War II.

“He was skipper of the PT boat that rescued JFK after their boat was cut in two by a Japanese destroyer in the South Pacific,” Liebenow recalled. “Serving in the military is sort of a family tradition.”

Since the Air Force wasn’t represented yet in his family, Liebenow went to the Air Force Academy and graduated in 1998. He didn’t have any grand aspirations.

“I was hoping to put in 20 years, but unfortunately cancer had other plans,” he said.

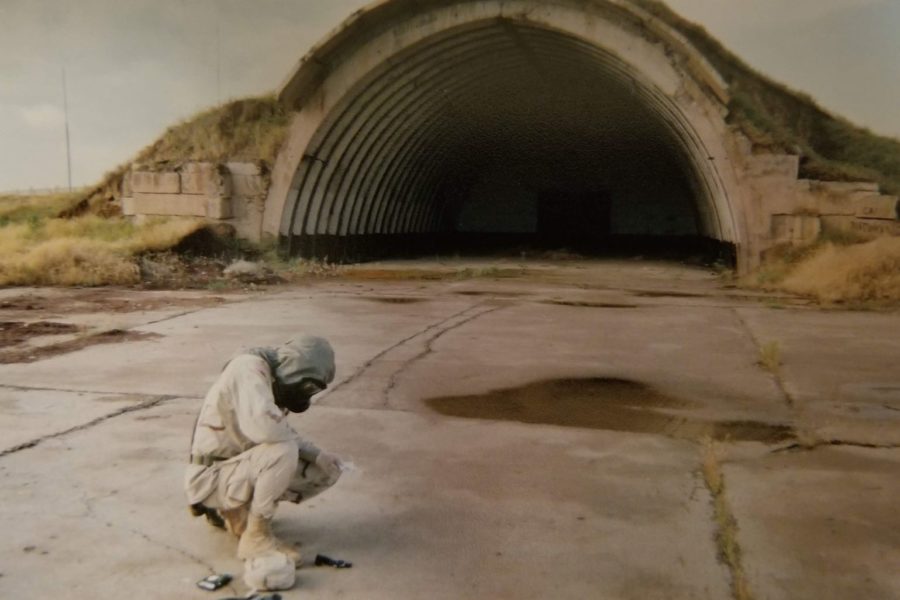

When he first arrived to K2, Liebenow slept on a cot alongside other Soldiers and Airmen in an old Soviet aircraft hangar. About a month later, he moved into a muddy tent city. Chemicals oozed up from the ground. Berms built around the encampment were known to emit radiation.

Declassified Defense Department documents from July 2020 reveal the Pentagon knew that the site of the forward operating base was heavily contaminated. It was a bombed-out chemical weapons factory where jet fuel had been dumped indiscriminately and radiation levels were unsafe. Still, it was the closest place Americans could begin the invasion to uproot Taliban rule.

Liebenow’s last few weeks at K2 were miserable. He threw up at night. Diarrhea repeatedly forced him into the snowy outhouse. Finally, he was put in an Army medical tent. He was so badly dehydrated that he required five IV bags. He recovered before returning to the U.S., where he married.

The rashes and itching didn’t start until he was deployed to Kandahar in 2002.

He did another brief rotation in Afghanistan, returning stateside in June 2002. He tried to have children for a year before he was told he had a low sperm count and could not conceive. By September 2003, not even two years after his deployment to K2, he was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and began chemotherapy and radiation. Liebenow was 28.

“About a year after radiation is when I slowly started being paralyzed on my left side and losing feeling on the right,” he said. He was medically retired from the Air Force in 2006.

The reaction to radiation grew to include severe headaches, bone damage that led to the amputation of his left arm, and skin cancer.

Still, Liebenow’s wife and their adopted daughter remained at his side. His countless surgeries were paid for by the Department of Veterans Affairs. But many of his comrades at K2 and others who served and were exposed to burn pits in Iraq and Afghanistan are still denied coverage.

Gillibrand estimates there are now 238,000 veterans on Afghanistan and Iraq burn pit registries. “And almost all of them are denied basic health care and coverage,” she said. Meanwhile, the K2 veterans group Stronghold Freedom Foundation estimates that there are about 2,500 Afghanistan war veterans who served at K2 but never set foot in Afghanistan and therefore do not qualify for service-related coverage.

“It seems like a no-brainer to me,” he said. “It doesn’t seem like a tremendous amount of money to support these people, even if they cannot definitively prove that their medical issues were caused by K2, to give them coverage because they answered the call right after 9/11.”

‘The Political Will is in Our Favor’

The cohort of service members who deployed to K2 would be covered under the PACT Act as would 3.5 million Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. Companion legislation known as the COST of War Act is also moving through the Senate.

“The bills do enough for us to get our foot in the door. At least the near-universal denials will probably stop,” said former Army Staff Sgt. Mark T. Jackson, a K2 veteran working on behalf of the Stronghold Freedom Foundation.

Jackson praised VA Secretary Denis McDonough for adding several specific diseases to the VA rules for veterans of Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, but he said more must be done.

He worries cost will again kill the bill.

“I have been told privately that the cost of this bill is prohibitive, making it unpalatable for some in the House and Senate,” he said.

The Department of Veterans Affairs did not respond to numerous inquiries from Air Force Magazine. The HVAC staffers also declined to provide information related to cost, but still expressed optimism.

“It seems like there is the political will right now to get this done,” an HVAC staffer told Air Force Magazine. “The chairman wants to get this done once and for all.”

The bill includes more than 23 presumptive conditions, including respiratory ailments, cancers, and reproductive issues.

Gillibrand likens it to the 9/11 legislation, a good starting point at which veterans can be helped right away, in some cases two decades after their exposure.

“I’m optimistic that we can keep our bill intact if it is reduced in size in terms of the number of diseases that are covered,” she said, noting how the 9/11 legislation took five years to conduct epidemiological studies.

“We will do the same thing with burn pits if necessary, and we will make sure all diseases are covered,” she said. “The sooner, the better.”