Photos/Illustrations: Jessica Turner/USAF; SSgt. Alexandre Montes

The US military is at constant war in cyberspace, fending off thousands of attacks and intrusions every hour by relentless foes seeking to exploit the slightest flaw in America’s defenses.

The daunting challenge for those in charge: Run a well-funded,-organized, -equipped, and -manned cyber force while keeping largely silent about the nature of the battle.

Cyber warriors are “constantly engaged in a fight with multiple adversaries,” said Maj. Gen. Christopher P. Weggeman, head of 24th Air Force, USAF’s component of US Cyber Command. “If you want to put on that superman cape and jersey and fight for your country, believe it or not, the most active warriors out there right now are the cyber warriors.”

What they do, though, must necessarily remain secret, so as not to tip off the enemy about what the cyber force knows, what it can do, and what it is doing. This presents a challenge to both recruiting and funding: The American people and lawmakers are largely unaware of who cyber warriors are, what it takes to train them, what it is they do, and what their challenges are.

Twenty-fourth Air Force—known as Air Forces Cyber—holds the reins for USAF’s responsibility in the three-part cyber mission set established by the Department of Defense. They are :

-

Defend the US against cyber attacks of significant consequence.

-

Secure, operate, and defend DOD’s networks and mission systems.

-

Support combatant commanders around the globe, delivering to them all-domain, integrated cyber effects.

Thus, it’s not cyberwar USAF is waging, but rather “cyber in war.”

These specialized warriors operate in, through, and from the cyber domain, helping the service fly, fight, and win, Weggeman told Air Force Magazine in an interview. While he thinks the service and Congress are coming closer to grasping this general philosophy, the public, he said, is probably not.

Cyberspace is a place, a domain—like air, land, or sea—Weggeman emphasized.

Unlike what is portrayed in movies—where troops at consoles fight video game-like battles in cyberspace, USAF’s digital warriors are “just one more weapon in an all-domain, integrated arsenal of effects in a whole-of-nation campaign,” he said.

There are 133 teams comprising the Cyber Mission Force, apportioned along the three guidelines set by DOD:

-

21 counter cyber teams operate in red space—the non-US government-controlled cyber realm—to defend the nation.

-

44 cyber strike teams operate in red space to support combatant commanders.

-

68 cyber hunter teams operate in blue space to defend DOD’s own cyber infrastructure.

-

More than 6,000 military, civilian, and industry cyber warriors make up this force. Of those, USAF alone puts forward more than 1,700 airmen, comprising 39 teams, again broken down by mission:

-

12 national mission teams for the Cyber National Mission Force

-

13 combat mission teams for US Strategic Command and US European Command.

-

14 cyber protection teams for USAF and US Cyber Command.

Twenty-fourth Air Force supplies more than a thousand Active Duty airmen for these missions. Twenty-fifth Air Force—with a focus on intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance—provides 700 Active Duty airmen. Another 500 airmen come from the Guard and Reserve.

TRIBAL WARFARE

There are four “tribes” in the cyber domain, Weggeman explained.

First is the senior leadership, providing administrative oversight and guidance.

Next are the cyber warriors who build, operate, and maintain networks in the cyber domain.

Third are the cyber warriors who conduct operations in, from, and through the cyber domain.

Finally, there are the consumers of cyber—the operators in other domains who nonetheless depend on the cyber infrastructure to do what they do.

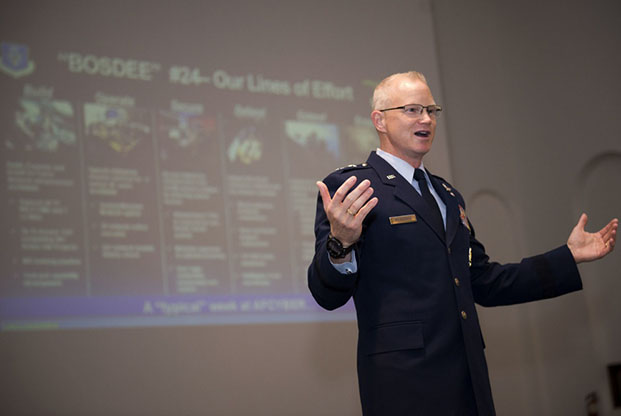

In 24th Air Force, Weggeman touts six lines of effort: build, operate, secure, defend, extend, and engage, or as he sums it up, “BOSDEE.”

Maj. Gen. Chris Weggeman, 24th Air Force Commander, breaks down “BOSDEE” during the 24th AF Community Open House April 6, 2017, at Port San Antonio, Texas. Photo: SSgt. Marissa Tucker

Each line requires a specialized and dedicated skill set and its own kind of Air Force cyber warrior.

SMSgt. Eric Von Holdt is a “grandfathered” cyber warrior, a specialist from before that term came into vogue.

He was in the right place at the right time when the Air Force created an enlisted track for the specialty. He “came into it because of the position I was in, and the job I was doing, and the skills I’d learned to get to that job,” he said in an interview.

He “grew up” in the Air Force as a traditional intel troop, climbing the ropes of digital network analysis, developing solutions in the information technology and networking domains. Today, he’s a cyber warrior with the 33rd Network Warfare Squadron, based at JBSA-Lackland, Texas.

The squadron monitors cyber systems throughout the service, from servicewide networks to individual ones. It looks for “bad things” cyber warriors are trained to find—such as code that shouldn’t be there or protocols taking place that shouldn’t—and wipes them out. That’s the “detect and respond” part.

Prevention is “reactive,” which Von Holdt explained means “looking for the things we don’t know about yet,” such as monitoring reports of new threats around the world, learning about them, and putting measures in place to block them.

He considers himself a natural fit for the mission, having a desire to figure out how things work, to build what doesn’t exist, and to seek solutions.

“If something is broken, I’m generally not okay with it being broken. I want to figure out why it’s broken and see if there’s a better way forward so it doesn’t break again,” Von Holdt said. “That, somehow, brought me to where I am.”

For airmen who can’t handle chronic change, the cyber domain will be a poor fit, Von Holdt said.

“This is a very stressful environment. Unlike in your physical domains, the rules are constantly changing,” he said, adding that this can be “aggravating.” Airmen in this field “have to be flexible.”

Being a leader in this domain presents similar headaches, said Capt. Mark Griffin of the 90th Cyberspace Operations Squadron at Lackland. Because there’s no precedent for some problems, there’s “lots of trailblazing going on.”

Frequently, “We have something that we know needs to be done and nobody who knows the right way of doing it,” Griffin said. “There’s a lot of creativity and challenge,” but sometimes friction “comes along with that ‘building the plane in flight,’ so to speak.”

For the last 18 months, Griffin’s been helping with the day-to-day operations of the 90th COS, developing cyber capabilities where they’re needed. Griffin wants cyber warriors to be more comfortable in their digital skins, more prepared to spot bad code.

“The more cyber-savvy people we have at all the varying levels, doing different jobs from acquisitions to operations to intelligence,” Griffin said, “the better we’re going to be at this.”

Von Holdt said the human cyber warriors are “the craziest, smartest nerds I have ever met in my life. They just astound me, coming up with the craziest solutions.”

_You can read this story in our print issue:

FLEXIBILITY IS KEY

As cyber technology improves, cyber warriors must stretch themselves and their equipment to cope with unknown unknowns; threats that attend the introduction of new material. Threats have to be imagined, solutions thought up, and the means to deliver them obtained in order to pre-empt new kinds of attacks.

“It’s constantly staying on top of ‘What new risks did that introduce?’ or ‘What new things do we have to defend against?’?” Von Holdt said, adding he’s certainly not expecting the service to suddenly triple the amount of airmen dedicated to cyber.

To survive an increasing demand for the mission with fewer resources, Von Holdt turned to efficiency, modernization, and increased agility.

Griffin sees the same challenge but through a different lens.

“Everybody wants to do the right thing, and people are realizing that we really need outcomes in cyber,” he said. “It’s easy for a general to say ‘We need to adopt more agile processes’—but then to see that executed successfully several levels downward for different mission sets, that’s definitely more of a challenge.”

While the acquisition community is working to become more agile, that very same advancement looms over the shoulders of the cyber community. Every solution could mean a new risk, creating a vicious and unrelenting cycle. That causes stress, and unremitting stress affects retention.

“My personal experience is that people don’t leave because of money,” Griffin said. “The biggest reason that I hear is that people want to make a positive difference but they feel like they have difficulty doing so.”

Those not involved in the mission may not value the cyber warriors as much as airmen fighting in other domains because they just can’t see the results.

Writing in Air & Space Power Journal, Weggeman claimed some troops “scoff” at cyber warriors because they “don’t pull triggers, drop bombs, or invade enemy strongholds.” But he also acknowledged the Air Force itself has painted all cyber warriors with a single brush, losing a sense of the varied contributions.

“We’ve over-homogenized our own cyber tribe. We have to get back into blocking and tackling,” he said. “To the point of ‘No one sees it. We’re not seen, we’re not heard, we’re almost invisible.’?”

The Air Force is working on it. Toward the end of 2017, Weggeman expects a team comprising 24th Air Force, the Air Staff, and its Chief Information Officer to begin pushing a new set of career paths to get the cyber force into the “modern maneuver-and-effects-centric” focus.

If everyone in the Air Force “is told and believes they’re a ‘cyberspace operator’?” in which the service attempts to “teach everything to everyone … you’re diluting their technical competency and you’re relegating yourself to this state of perpetual amateurism,” Weggeman said. Navy SEALs “go to SEAL training for a reason,” he noted. “It’s different.”

Cyber warriors watch their monitors in April 2016 at US Cyber Command facilities in Port San Antonio, Texas. Photo: USAF

BETTER WAY TO BUILD A FORCE

Finding the right people takes hard work and more than a little luck.

When Von Holdt was operating in the pre-Cyber Command days, war was less emphasized.

The cyber force was rapidly evolving and the Air Force was figuring it out as it went along. Jobs were handed over to those who could do them. Despite never having gone to tech school, Von Holdt became a cyber warrior and has since taught courses and helped develop new warriors.

“The old mindset was, ‘Is email working? Okay, our job is done,’?” Von Holdt said. “Now it’s: ‘Is email safe and secure?’ That’s probably more important than if it’s working.”

One of the responsibilities of 24th Air Force is to build the new cyber warriors.

Lt. Col. Angela Waters is the 39th Information Operations Squadron commander. Her job is simple: Take airmen from Air Education and Training Command who did “really well” on their initial cyber skills course and turn them into cyber warriors.

In Fiscal 2017, Air Force Space Command—which oversees Air Forces Cyber—tasked Waters with creating 1,500 cyber warriors. In FY18, AFSPC wants 1,600 in the pipeline. This is the goal, not necessarily the actual throughput, Waters pointed out.

“We try to get as many students through the pipelines as we possibly can,” Waters said in an interview. “For the most part, we fill every seat in every class.”

The schoolhouse runs 18 different courses, focused on two types of operations: information and cyber.

More than 100 airmen are studying at any given moment between a main campus at Hurlburt Field, Fla., and a squadron detachment at Lackland. Assuming they pass every course, an aspiring cyber warrior will get a little over four months of training at this level.

Waters said one of her biggest challenges is the slow pace of change at the 39th itself despite the high tempo and evolving need for bodies.

“We need to grow,” she said, but the field is already growing faster than it ever has, and it’s hard to keep up.

Von Holdt argued that good cyber warriors aren’t created in the classroom. While cyber training in USAF has come a long way, he said, it’s really aptitude more than knowledge that determines the value of a cyber warrior. The cyber force needs tactically competent airmen to connect two disparate pieces of information and figure out what’s going on, he explained. If someone is lost once the mission deviates from a checklist, they’re not very useful in today’s cyber domain.

“It’s trial by fire. You find the people that you think are going to be good, you give them all the training you can, and then you sit them down and have them go to work,” he said. “Sometimes people excel at that. Other times, it’s just not the job for them. And that’s not any fault of their own, at all.”

Expertise is in writing and reading code, a set of inflexible zeros and ones whose executed functions are binary: yes or no. Despite the differences, their work can have the same effect as that of, say, combat pilots.

Cyber warriors have to have the same ethos as any other fighters, said Weggeman, an F-16 fighter pilot for 25 years. “It’s immutable.” The difference is, instead of bombs and missiles, cyber warriors throw code at the enemy. That can be a problem, because while pilots can measure what they do—targets destroyed—cyber warriors can’t necessarily see the results of their actions. It’s even harder to offer them praise, because the Air Force can’t share their achievements publicly. That would give the adversary clues as to vulnerabilities, the threats USAF takes most seriously, and the steps used to confront them.

Neither Von Holdt, Griffin, Waters, nor Weggeman could offer much in the way of concrete examples describing what they do or how they do it. The words they’re compelled to use—when they can say anything at all—are thick and technical.

Cyber protection experts at Scott AFB, Ill., run through an exercise to validate their abilities to locate, defend, and counter attacks. Photo: A1C Daniel Garcia

For example, Griffin’s 90th COS was tasked recently with presenting a red team in a cyber threat emulation. Deadlines approached quickly and Griffin, stuck between the need to deliver this capability and many others, found his squadron stretched thin. This was a situation requiring some innovation.

“I’m a make-it-happen kind of guy,” he said, explaining that he immediately turned to leadership, to whom he described the situation, normal procedure, and why it wouldn’t work on this occasion.

“Here’s the facts, here’s the operational reality,” he related, saying he told leadership, “?‘I need you to waiver some policy or make the case upward so we can get [an] exception to make the mission happen.’?”

On this occasion, it worked. But how can the Air Force reward Griffin for thinking outside the box in this episode or recognize his cyber warriors for creativity and increasing efficiency without exposing holes in the 90th’s capabilities

The service is working toward better recognition of its cyber warriors. That will always be difficult in this domain because, considering the classified nature of cyber operations, the people getting recognized have to be brought into a Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility (SCIF)—a space specially protected from electronic eavesdropping of many kinds—and we “give them an award that doesn’t exist and that they can never wear,” Weggeman observed.

Recognizing his airmen who contribute and get the mission done is crucial, Weggeman insisted, describing it as “universal to the success of any service culture.”

He added, “I’m working on that.”