Without U.S. air power, United Nations forces would have lost Korea in 1950.

The North Korean invasion force crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea at 4 a.m. on Sunday, June 25, 1950. Seven infantry divisions were supported by 150 T34 tanks and more than 100 combat aircraft.

In three days, it easily swept aside the under-equipped South Korean army and captured Seoul, capital of the Republic of Korea (ROK).

The United Nations Security Council called for withdrawal. The Soviet delegate, no doubt, would have vetoed the resolution, but he was absent, boycotting Security Council meetings because of an unrelated matter.

Except for air power, ‘the war would have been over in 60 days with all Korea in Communist hands.’Gen. Matthew Ridgway, U.N. forces commander

The U.N. asked member nations to help South Korea repel the invasion. U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur was named commander of all U.N. forces in Korea. The U.N. command consisted mainly of Americans and South Koreans, with smaller representation from two dozen other nations.

President Harry S. Truman ordered U.S. air and naval forces to provide military cover and support for the South Korean army. The first U.S. units to engage, on June 27, were from Far East Air Forces (FEAF).

Eighth Army ground units, drawn from occupation duty in Japan, arrived July 1. Like the ROK forces, they were pushed back by the oncoming North Koreans and set up a defensive perimeter around the port of Pusan at the southern end of the peninsula.

North Korea’s plan was to seize control of all of South Korea in a month or less, before the United States could effectively come to the rescue. But that scheme was spoiled by U.S. air power, which conducted 7,000 close support and interdiction airstrikes in July and slowed the North Korean rate of advance to two miles a day.

That gave U.S. and U.N. forces time to regroup and consolidate their reinforcements behind the defenses of the “Pusan perimeter,” 50 miles wide and 100 miles deep. The retreat finally came to a halt on Aug. 4. Gen. Matthew Ridgway, commander of U.N. forces from 1951 to 1952, said that except for air power, “the war would have been over in 60 days with all Korea in Communist hands.”

The U.N. counteroffensive began Sept. 15 with MacArthur’s dramatic landing at Inchon, behind enemy lines, combined with a breakout from Pusan. Within two weeks, U.N. forces were inside North Korea, eventually reaching the Yalu River. However, China entered the war in November, driving the U.N. back southward. By the spring of 1951, the ground conflict had narrowed to a strip above and below the 38th parallel.

The Korean War lasted for 37 months, but after truce talks began in July 1951, the last two years were essentially a stalemate with the opponents positioned on opposite sides of the 38th parallel.

All of the big movements were in the first year, when the battlefront shifted between the Pusan perimeter in the south and the Yalu in the north. Most of Korea—including the two capitals, Seoul and Pyongyang—changed hands at least twice.

Dimensions of Air Power

The overwhelming images of the Korean War are of the ground battle: Inchon, Pork Chop Hill, Heartbreak Ridge, the “Frozen Chosin,” Imjin.

The role of air power in Korea has never been well understood. Remembrance of it concentrates on the duel of jet fighters in “MiG Alley” along the Yalu, which separates North Korea from Manchuria.

Achievements in MiG Alley were important, but that was the lesser part of Air Force involvement. Far East Air Forces flew almost four times as many close air support and interdiction sorties as it did counter-air. Of total FEAF sorties during the war, only 12 percent were counter-air.

The aerial engagements themselves were a means to achieve greater strategic objectives. FEAF confronted the MiGs on the Manchurian border, which enabled the U.N. to keep control of the air over North and South Korea. Ground forces were free to operate without attack or interference by enemy air power.

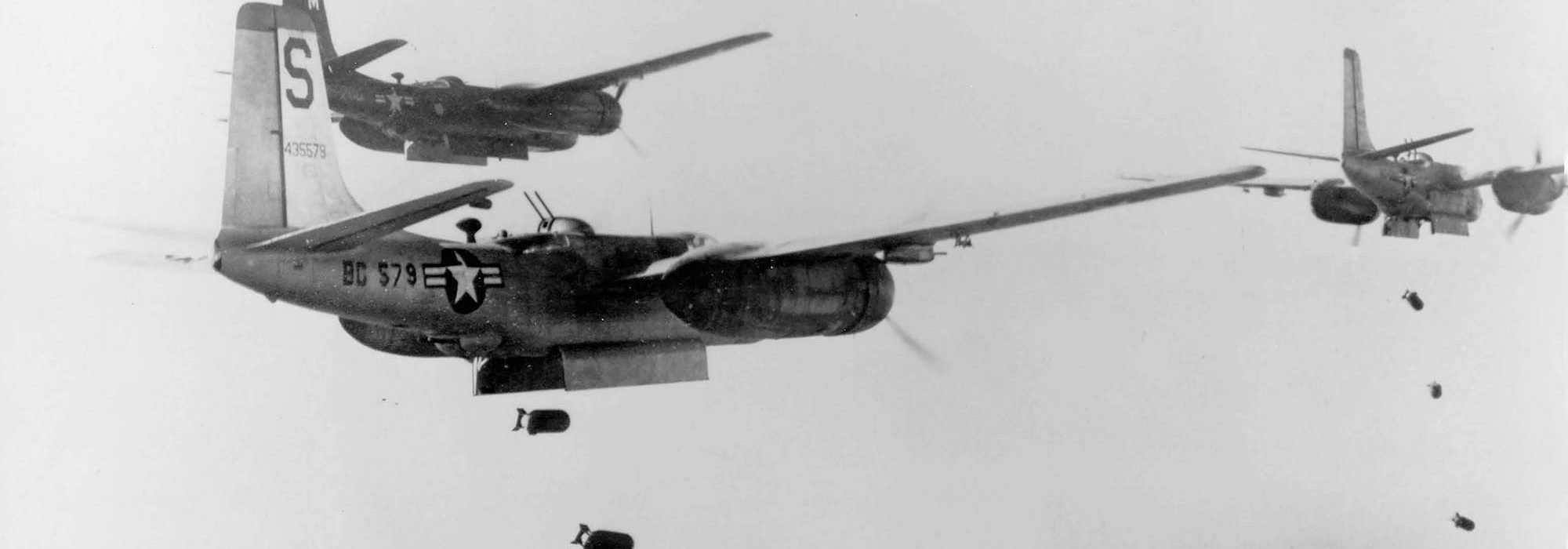

FEAF, with headquarters in Japan, had about 400 combat aircraft in Japan, Okinawa, Guam, and the Philippines at the outset of the war. That included a large number of fighters as well as B-26 and B-29 bombers. They were soon reinforced by additional aircraft from bases in the United States.

Then and later, the Army was reluctant to give the Air Force credit for significant results in Korea. A study for the Army chief of military history in 1966 said that air interdiction had been “helpful during the early months of the war in assisting the ground forces to overcome the North Korean army” but that “the air interdiction campaign was not a decisive factor in shaping the outcome of the war.”

A considerable part of the Army attitude had to do with control. In July 1950, for example, the Air Force sent three additional wings of B-29 bombers to Korea. Army officers in Far East Command wanted them employed exclusively for close air support and reacted badly when they were not.

Army Maj. Gen. Edward Almond, Far East Command chief of staff, concluded, “The only assurance a ground commander can have that any supporting arm will be employed effectively, or at all, is by having operational control over that supporting arm.”

Police Action

At the end of World War II, the U.S. accepted the Japanese surrender south of the 38th parallel and the Soviet Union accepted the surrender north of that line, which became the arbitrary boundary between North and South Korea. In 1949, the last U.S. troops departed Korea, leaving only a military advisory group.

South Korean armed forces had 100,000 soldiers, but lacked tanks and heavy artillery. The air force consisted of 20 liaison aircraft or trainers. North Korea had an army of 130,000, supported by 500 tanks and artillery pieces and 132 combat airplanes supplied by the U.S.S.R.

The U.S., in 1950 did not regard Korea as being of great strategic importance—but believed the Soviet Union was behind the invasion, making it a challenge by world communism that had to be met.

Truman, hoping to head off alarm that Korea was a major conflict, declared June 29 that the United States was “not at war” and that the combat operations were a “police action” on behalf of the U.N.

The first engagement of U.S. ground forces was a disaster. “Task Force Smith”—a cobbled-together battalion of about 400 men, commanded by Lt. Col. Charles Smith, with no tanks or effective anti-armor weapons—took a defensive position just north of Osan on July 1. The North Koreans routed them in a matter of hours, inflicting casualties of almost 50 percent.

B-26s, along with Air Force and Navy fighters and B-29s flying from Okinawa, bombed airfields and railroad yards in North Korea, then patrolled the major routes over which the enemy was advancing.

U.N. forces fell back toward the Pusan enclave. With more American reinforcements pouring in by the day, the North Korean advance came to a halt on Aug. 4. By then, air power from FEAF and the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 77 had severely reduced the troops and tanks of the invasion force and made a shambles of the supply system. The North Korean air force was effectively destroyed, with only about 20 airplanes remaining.

Most of the major industrial targets in North Korea had been destroyed by air power and early September marked the end of the North Korean People’s Army as a fighting force.

From Pusan to the Yalu

MacArthur delivered his boldest stroke of the war Sept. 15, an amphibious landing behind enemy lines at Inchon, 25 miles west of Seoul. The North Koreans were not ready to defend the position.

Two U.S. Marine regiments led the assault, meeting little resistance and incurring fewer than 200 casualties in capturing Inchon. In less than two weeks, U.N. forces were again in possession of Seoul and astride the North Korean route to the south. FEAF air power, which slowed the effort to reinforce Inchon and Seoul, contributed to the operation’s success.

Concurrently, U.N. forces broke out of Pusan and surged northward against the weakened enemy. They were soon across the 38th parallel and reached the Yalu on Oct. 26.

In October, four months after the invasion, it appeared that the war was almost over. MacArthur told Truman that North Korean resistance would be ended by Thanksgiving and that he hoped to withdraw the Eighth Army by Christmas. Two of the B-29 bomb groups were sent back to the United States.

The course of the conflict changed overnight when China intervened with 300,000 troops, outnumbering MacArthur’s U.N. force by almost 2-to-1. The Chinese were not just reinforcing the North Koreans. They were taking over the war. U.S. and ROK ground forces were stopped and thrown backward.

MiG Alley

The Chinese intervention brought a big change in the caliber of enemy air power. Russian-built MiG-15 interceptors, first seen on the Korean side of the Yalu on Nov. 1, were 100 mph faster than FEAF’s best fighter, the F-80 Shooting Star.

The MiGs had Chinese markings, but they were flown by Russian pilots. It was not until later in the war that Chinese and North Korean pilots began to fly some of the missions.

Ironically, in the first all-jet engagement on Nov. 8, an F-80C shot down a MiG-15. Various kinds of U.S. aircraft defeated MiGs on occasion, but no American fighter could match the capabilities of the MiG-15 until the arrival in December of the swept-wing F-86 Sabres.

MiGs remained dominant through the winter of 1950-51 because of their greater numbers and because the U.N. retreat into South Korea forced the F-86s to abandon their forward airfields and pull back to Japan, from where they could not reach the MiG stronghold on the Yalu.

The Sabres returned to their Korean bases in the spring counteroffensive and soon established air superiority. Navy and Marine Corps aviators got some of the MiGs but their best fighter, the Grumman F-9F Panther jet, was outclassed by the MiG-15, so they put most of their effort into air-to-ground sorties, leaving the counter-air mission largely to FEAF.

According to the Air Force’s assessment immediately following the war, U.S. fighters shot down 14 enemy aircraft for every USAF aircraft lost in battle. After further examination of the claims, the ratio was dropped to 10-to-1. Other studies suggest that a 7-to-1 ratio—or even lower—would be more accurate.

Whatever the actual ratio was, a force of F-86s that never exceeded 150 outperformed the MiG-15s in theater, which numbered more than 900 at their peak. The Chinese were never able to project air power against U.N. targets or forces.

Retreat and Recovery

Chinese and North Korean forces crossed the 38th parallel on Christmas Day and reached their deepest penetration at Wonju, southeast of Seoul, on Jan. 14, 1951. As U.N. armies struggled to gain traction, air power carried the fight to the enemy.

The deputy commander of Chinese forces in Korea said later that in the early stages of the war, American aircraft and artillery had destroyed 42.8 percent of Chinese trucks.

Airstrikes did not interdict the invasion completely. One reason was that the enemy’s supply requirements were minimal. A Chinese division could get by on 40 tons of supplies a day, compared with the 500 tons needed to sustain a U.S. division. Furthermore, the North Koreans and Chinese could bring in massive labor resources to keep their lines of communication.

The U.N. counteroffensive began, and gained strength, recapturing Seoul on March 18, the fourth and final time the south Korean capital changed hands.

The rift widened between McArthur and officials in Washington. In defiance of Truman and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, MacArthur called for attacks into China unless a peace settlement was reached. Truman fired MacArthur on April 9 and replaced him with Ridgway.

By July, the battlefront—which had rolled up and down the peninsula like a window shade in the first year of the war—settled down to a stalemate. The dividing line ran across the two Koreas from southwest to northeast at an oblique angle to the 38th parallel.

Stalemate and Truce

North and South Korea “were ready to fight to the death,” but China, the U.S.S.R., the U.S. and the U.N. were not, said Army historian Andrew Birtle. “Twelve months of bloody fighting had convinced Mao Tse-tung, Joseph Stalin, and Harry S. Truman that it was no longer in their interests to try and win a total victory in Korea.”

“Since the political leaders of the two warring factions had signaled their willingness to halt the fighting, generals on both sides proved reluctant to engage in any major new undertakings,” Birtle said. “The two sides exchanged artillery fire, conducted raids and patrols, and occasionally attempted to seize a mountain peak here or there, but for the most part, the battle lines remained relatively static.”

During the three years of war, U.N. air forces flew 1,040,708 combat and combat support sorties. The U.S. Air Force flew the majority of them (69.3 percent), followed by the U.S. Navy (16.1 percent), the U.S. Marine Corps (10.3 percent), and other allied air forces (4.3 percent).

Formal truce negotiations began at the village of Panmunjom in October 1951, but it took two years to agree on the armistice, which went into effect July 27, 1953. The truce line and the corollary Demilitarized Zone ran east to west from Kaesong on the Yellow Sea to Kosong on the Sea of Japan.

Sparse Credit

The popular interpretation is that air power in Korea was a sideshow, if that. “In Korea, the USAF belief in ‘victory through air power’ was put to the test and found sorely wanting by many of those who were promised so much from it,” said British historian Max Hastings.

It is valid to say that air power was not decisive in Korea—but then, nothing else was decisive either. It was stalemate after the first year, and the conflict ended in a truce.

- Without FEAF air power, North Koreans would have captured all of South Korea in a month, driving out U.S. and South Korean forces.

- The Air Force held control of the air over North and South Korea. Enemy aircraft were seldom encountered south of Pyongyang. U.N. ground forces were free from air attack. Their supply lines and infrastructure were not bombed.

- North Korea had 75 airfields that could have supported MiG-15s, but U.S. air power put them out of business. After 1951, the enemy abandoned any serious effort to operate air bases in North Korea.

- Air attacks destroyed every vestige of industry in North Korea, although armaments still came from outside nations.

- FEAF air power killed as many as 150,000 enemy troops and destroyed large numbers of tanks, trucks, trains, bridges, and buildings. Navy and Marine Corps airstrikes added to the totals.

All that adds up to something better than the sparse credit usually acknowledged for air power in Korea.

John T. Correll was editor in chief of Air Force Magazine for 18 years and is a frequent contributor. His most recent article, “Hitler’s Buzz Bombs,” appeared in the March issue.