Guetlein to Lead ‘Golden Dome’ Missile Shield Program

By Chris Gordon

President Donald Trump aims to deploy his signature Golden Dome missile defense shield before the end of his term and he picked the Space Force’s No. 2 officer, Gen. Michael A. Guetlein to lead the effort.

“This is very important for the success and even survival of our country,” Trump said in announcing his plan. “It’s an evil world out there, so this is something that goes a long way toward the survival of this great country.”

Guetlein is well-suited to the role, having led Space Systems Command, the service’s primary procurement agency, prior to becoming Vice Chief of Space Operations, where he took part in the Pentagon’s Joint Requirements Oversight Council, a key panel overseeing major acquisition programs.

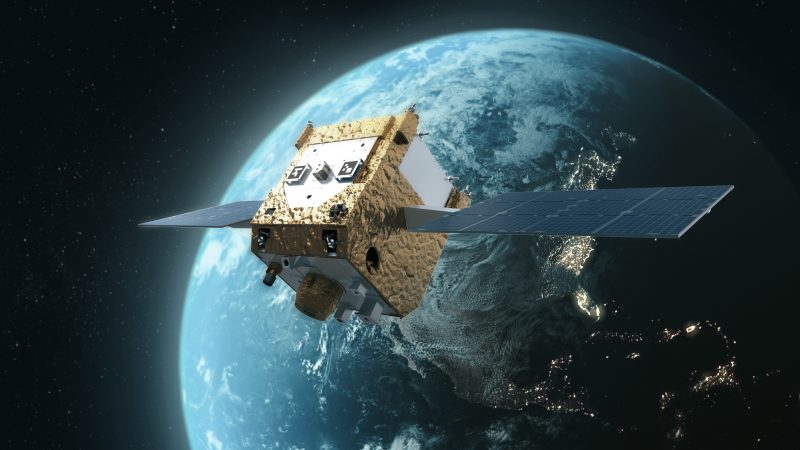

Golden Dome will require integrating sensors and shooters in space, on the ground, and at sea in a complex network to protect the U.S. homeland. While likened to the Iron Dome system over Israel, Golden Dome envisions a defensive shield over the entire United States, an area 441 times larger.

Trump said he wants to finish the project in “less than three years,” an extremely aggressive timeline for which there is no precedent for delivering such a complex system. The President promised a “state-of-the-art system that will deploy next-generation technologies across the land, sea, and space, including space-based sensors and interceptors.”

Golden Dome will be a “system of systems,” integrating existing technology, new satellite sensors, and potentially space-based missile interceptors. “This design for the Golden Dome will integrate with our existing defense capabilities and should be fully operational before the end of my term,” Trump said. “Once fully constructed, the Golden Dome will be capable of intercepting missiles even if they are launched from other sides of the world, and even if they are launched from space.”

China and Russia called the system destabilizing, and critics have suggested it could unleash a nuclear arms race. But proponents see in Golden Dome the same ambitious, cost-imposing challenges posed by President Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative in the 1980s, a system some say contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Trump estimated Golden Dome could cost about $175 billion—but that could be only a down payment for a program likely to evolve over a far longer period than its initial three years. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office pegs the cost of Golden Dome at $542 billion over the next 20 years.

The administration is seeking the first $25 billion installment in the Republican-led tax reform and spending bill passed in May by the House and now awaiting Senate action at press time.

“We will truly be completing the job that President Reagan started 40 years ago, forever ending the missile threat to the American homeland,” Trump said. “This is something that’s going to be very protective. You can rest assured, there’ll be nothing like this. Nobody else is capable of building it, either.”

In testimony before Congress in March, Guetlein compared Golden Dome to the Manhattan Project. The Space Force’s No. 2 often warns of the new dangers America faces and defends the creation of a separate space-focused service and its niche capabilities.

“Our adversaries have become very capable and very intent on holding the homeland at risk,” Guetlein said. “Our adversaries have been quickly modernizing their nuclear forces, building out ballistic missiles capable of hosting multiple warheads, building out hypersonic missiles capable of attacking the United States within an hour and traveling at 6,000 miles an hour, building cruise missiles that can navigate around our radar and our defenses, building submarines that can sneak up on our shores, and, worse yet, building space weapons.”

Congress will ultimately have to go along. And while lawmakers welcome the concept, some expressed concern about the speed, cost, and realism required to execute the president’s vision.

“To build a system over the entire country would be incredibly hard, and we’re not sure it’s going to work,” said retired NASA astronaut Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.) at a Politico event in May.

Sen. Jack Reed (D-R.I.), ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee told reporters in May that the details must be explained. “They have to identify the technologies,” Reed added. “They have to go ahead and design an integrated plan. From what I’ve heard, it’s more of a warning system than it is a firing system, although they will develop firing units to complement it. But the key now is to identify [incoming] hypersonic [weapons] as soon as they launch, so that we can engage them. That’s still a work in progress.”

Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman said the challenge will be the many advanced elements “that you have to stitch together in very technical ways.”

“You don’t buy Golden Dome,” he said, explaining that challenge. “You orchestrate a program that includes a lot of programs … it’s a system of systems.” The trick will be in identifying “which systems are critical … which ones are affordable, and which ones are practical in terms of the technology we can rapidly bring to bear.”

SPACECOM Wants to Be Dynamic in Orbit. The Question Is How?

By Greg Hadley

U.S. Space Command wants to be able to maneuver satellites without having to worry about conserving fuel. But figuring out how remains an open question, says SPACECOM’s deputy commander.

“Dynamic space operations” promise to make space assets more effective, said Army Lt. Gen. Thomas L. James while visiting AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. “We’ve done enough of the exercises, we’ve done enough of the training … and see what dynamic maneuver would do for us if we had it.”

SPACECOM Commander Gen. Stephen N. Whiting strongly stated his support for “on-orbit logistics and infrastructure” a year ago at the 2024 Space Symposium. Such capabilities would enable refueling by spacecraft equipped to do refueling and repair.

“Refueling has some disadvantages … because it’s a big fat target, depending on how you establish your refueling systems,” James said. Yet “our analysis … kind of shows there’s a real case for the refueling.”

The Space Force remains unconvinced. USSF is responsible for developing and acquiring space capabilities, while SPACECOM is the operational command responsible for combat in space.

Lt. Gen. Shawn Bratton, deputy chief of space operations for strategy, plans, programs and requirements, questioned the concept only days earlier: “I don’t know that I see the clear military advantage of refueling,” reported SpaceNews. And Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman told Congress last year that the Space Force was still weighing the benefits and cost of refueling.

At this year’s Space Symposium, industry and defense officials described plans for on-orbit demonstrations in 2026 and 2028. But foreshadowing Bratton’s comments, Lt. Gen. Philip A. Garrant told reporters he was waiting for the refueling “business case” to be proven.

One alternative to extending satellite life with additional fuel could be rapid satellite deployment. James acknowledged that May 8, saying: “If General Bratton were here right now, he’d say, ‘Or, I just give you more satellites rapidly, and that’s cheaper and easier for us to do than refueling.’”

Operationally speaking, SPACECOM sees a clear need to move satellites around when needed, which is why SPACECOM and USSF’s SpaceWERX innovation shop plans to award 10 contracts worth $1.9 million each for small companies to demonstrate technologies in a “Sustained Space Maneuver Challenge.”