The building shook for only an instant and the soot from the smoke was clean within 48 hours, retired Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula recalled two decades after the 9/11 attack on the Pentagon. But America’s national security priorities had been lost in the fog of war for a generation. Only now is strategy again aligning with threat.

An externally focused defense strategy turned to the homeland after the al-Qaida attacks, consolidating intelligence and protecting the nation against another terrorist attack, but mission creep led to strategic errors that would set the nation behind adversaries, said Deptula, now the dean of AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, in an interview with Air Force Magazine as he reflected on the 20th anniversary of 9/11.

On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, then Maj. Gen. Deptula was dressed in his blues sitting at his Pentagon office at 5D156. He was director of the Air Force 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review. After the attack, he would be called in to design the air response against the Taliban, putting him at the center of an evolving assessment of global terrorist targets against an evasive enemy, hampered by burdensome restrictions and patchy intelligence.

Deptula was two corridors down from where American Airlines Flight 77 would strike the west wall of the Pentagon.

“I’m sitting at my desk, and I get a call from my deputy, Brig. Gen. Ron Bath… He said, ‘Hey, General Deptula, turn on the TV,’” Deptula recalled.

American Airlines Flight 11 had struck the North Tower of the World Trade Center at 8:46 a.m.

“It was just a beautiful day, up and down the East Coast. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky; crisp, wonderful, blue sky day,” Deptula recalled, wondering how a pilot could hit the building.

“Then, as I’m watching, wham! Here comes the second, and immediately, everyone who did watch it, when they saw the second airplane, it’s like, ‘This isn’t an accident,’” he said.

“This is an intentional attack,” he continued. “And the next thought that went through my mind, I’ll always remember this as well: ‘You know, the Pentagon would make a logical third target.’”

The Building Shook for an Instant

Thirty-four minutes after Deptula watched American Airlines Flight 175 crash into the South Tower of the World Trade Center, he heard a muffled explosion and felt a momentary quake.

The Pentagon had been hit by American Airlines Flight 77.

“The building shook, just for an instant,” Deptula recalled, ascertaining what had just happened. “The alarms went off almost immediately.”

The two-star directed staff to account for everyone in his division and once the task was complete, he dismissed them for the day. He himself was dismissed while critical staff, including the Joint Chiefs, assembled at the alternate command center at Bolling Air Force Base, now Joint Base Anacostia–Bolling, in Southeast Washington, D.C.

The remainder of the afternoon was a hectic effort to get home: Walking past closed Pentagon exits, observing smoke and fire from across the inner courtyard, unable to reach his wife with downed cell service. Finally, Deptula walked out the Pentagon river entrance and across the street to the marina, where he watched news reports on a small portable TV and conducted an interview with Washington Post reporters while waiting for a lift home.

“One of the biggest things I noticed was the quiet, the silence,” he recalled. “It was quiet. Black smoke billowing over the other side of the Pentagon, the opposite side from the river entrance, and then here are these two F-16s orbiting overhead. That’s why I say, ‘This was surreal. It’s quiet. The Pentagon’s on fire, two Air Force F-16s doing combat air patrol over Washington, D.C. Just eerie.’”

Deptula went into work at the damaged and soot-covered Pentagon the following day, only to be sent home until the intact part of the structure could be cleaned and secured.

Returning to work on the Air Force QDR seemed distant with the nation poised to strike back at an as-yet undefined enemy.

“The thing that you begin to think about is, ‘Who’s responsible for this? Where are they located? What are the options for response?’” Deptula recalled. He had already begun to share his operations experience as principal attack planner for Desert Storm in the Pentagon’s Checkmate wargaming center. There, he heard some of the ideas under consideration by U.S. Central Command contingency planning cells.

Then, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. John P. Jumper called Deptula into his office.

“‘I just got a call from Chuck Wald, the 9th Air Force Commander,” Deptula recalled Jumper saying. “‘He’d like you to deploy to Southwest Asia to become the commander of the [U.S. Air Forces] Central Combined Air and Space Operations Center to design the response, plan the response, and help in the execution of our response. Do you want to go?”

Striking Back at the Taliban

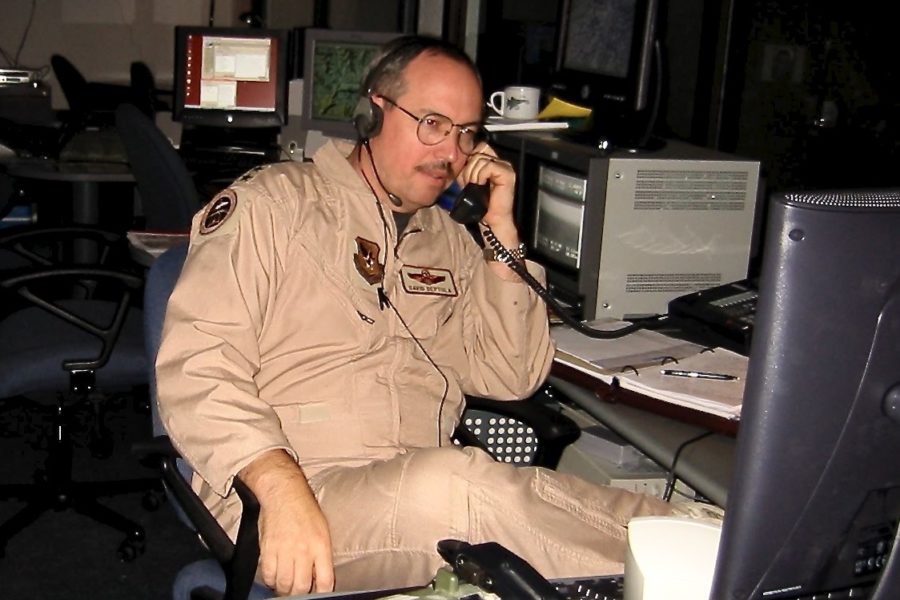

Deptula settled into his new role at Prince Sultan Air Base, southwest of the Saudi capital of Riyadh, within days of the 9/11 attacks. He would be responsible for designing the initial attacks on the Taliban and al Qaeda that commenced on Oct. 7, 2001.

Many strategic options were on the table from a cover for invading Iraq and removing Saddam Hussein to launching simultaneous counter-terrorism activities globally. As intelligence came in, options were refined. At one point, the United States even proposed working together with the Taliban.

“Very early on, we offered the Taliban the option to work with us to help us kick out al-Qaida,” Deptula said. “Then it became evident that they did not want that. Then we kind of raised the stakes in the context of, ‘Well, if you’re not going to do that, then you are liable for protecting our adversary and will come under attack as well.’”

CENTCOM planners wanted to assure that the people of Afghanistan knew this was not an attack on them, but on the Taliban who were harboring al-Qaida.

But limitations were plentiful, and strategic errors ensued.

“We could not drop a bomb in Afghanistan without approval of the four-star commander of Central Command, which was ridiculous,” Deptula remembered. Infrastructure was off limits.

The command wanted roadways and lines of communication to be in place to move humanitarian assistance to the people of Afghanistan.

The restriction led to one of “the most grievous strategic errors” of the war, Deptula recalled, allowing Taliban leader Mullah Omar and the senior most Taliban leadership to enter a compound in Kandahar and not strike.

“This is like manna from heaven to combat planners because I can take out the senior Taliban leadership and all of their senior staff on the first night of the war,” Deptula remembered. “I’m talking to the commander of the Predator outfit going, ‘What the hell is going on? Why is this taking so long to get approval?’”

Approval did not come. Concerns about mud huts within the collateral damage circle prevented the strike.

Nonetheless, the coordination of airpower with the “light touch” of special operations forces and the indigenous forces of the Northern Alliance led to the collapse of the Taliban government by December.

“We’d already accomplished our critical U.S. national security objectives in Afghanistan,” Deptula said, noting his own departure in mid-November.

“We’d removed the Taliban from power. We had worked to assist a government friendly to the United States and our interests in their place, and we’d eliminated the al-Qaida terrorist training camps inside Afghanistan,” he said. “What we should have done was [say], ‘See you later, have a nice life. If you do it again, we’ll be back.’”

‘Unobtainium’ Mission Creep

The mission in Afghanistan had been accomplished even before Central Command finished deploying its land forces. Instead of fighting, the military took a non-military role, Deptula assessed.

“By the time they got into theater, they realized, ‘OK, the Taliban are gone. Friendly government. Al Qaeda is gone. Now, what do we do?’” he said. “So, in the largest example of mission creep, they sought to win hearts and minds and change a collection of sixth-century tribes into a modern Jeffersonian democracy, which is what we’ve been trying to do for the last 20 years. But it’s unobtainium. Nor is it a military mission or role.”

Institutional equities butted heads, Deptula opined, as the Army fought to “prove their relevancy” in the wake of a decade of swift air successes that preceded 9/11, from Bosnia to the Gulf War. The investment and commitment of U.S. forces in Afghanistan would bog down the American military for two decades while adversaries like China invested in military modernization.

“9/11 happened. And it had an enormous strategic effect on the government and the military of the United States,” Deptula offered.

America’s defenses had always been faced externally. Important changes were made. The Department of Homeland Security was stood up, the Intelligence Community was united under the Director of National Intelligence and the Transportation Security Administration was established.

“We are more attuned to terrorism as a critical national security threat than we ever have been before,” Deptula said.

In Afghanistan, changes in military strategy hampered the American force.

“When we shifted from a strategy of counterterrorism to one of counterinsurgency, we shifted from a set of objectives that were in the U.S. critical national security interest to a set of objectives that were not, and that’s very frustrating,” Deptula said. “We shouldn’t get counterterrorism confused with counterinsurgency and getting involved with nation building and trying to change other nations into our image.”

The United States neglected future threats by continuing to push for total success in Afghanistan, he said.

“As the world’s sole superpower, we need to be able to be prepared to deter, and if necessary, defeat threats across the spectrum of conflict, from humanitarian assistance all the way up to global thermonuclear war,” Deptula said. “The pendulum swung too far.”